The modern interpretation of heat is, or course, somewhat different to Lavoisier's

calorific theory. Nevertheless, there is an important subset

of problems, involving heat flow, for which Lavoisier's approach is

rather useful.

These problems often crop up as examination questions.

For example: ``A clean dry copper

calorimeter contains 100 grams of water at 30![]() degrees centigrade.

A 10 gram block of copper heated to 60

degrees centigrade.

A 10 gram block of copper heated to 60![]() centigrade is added. What is the final

temperature of the mixture?''.

How do we approach this type of problem? According to Lavoisier's theory, there is an

analogy between heat flow and incompressible

fluid flow under gravity.

The same volume of liquid added to

containers of different (uniform) cross-sectional area fills them to different heights.

If the volume is

centigrade is added. What is the final

temperature of the mixture?''.

How do we approach this type of problem? According to Lavoisier's theory, there is an

analogy between heat flow and incompressible

fluid flow under gravity.

The same volume of liquid added to

containers of different (uniform) cross-sectional area fills them to different heights.

If the volume is ![]() , and the cross-sectional area is

, and the cross-sectional area is ![]() , then the height is

, then the height is

![]() . In a similar manner, the same quantity of heat added to different bodies

causes them to rise to different temperatures. If

. In a similar manner, the same quantity of heat added to different bodies

causes them to rise to different temperatures. If ![]() is the heat and

is the heat and

![]() is the (absolute) temperature then

is the (absolute) temperature then

![]() , where the constant

, where the constant ![]() is termed the heat capacity.

[This is a somewhat oversimplified example. In general, the heat capacity is

a function of temperature, so that

is termed the heat capacity.

[This is a somewhat oversimplified example. In general, the heat capacity is

a function of temperature, so that

![]() .]

If two containers, filled to different heights,

with a free-flowing incompressible fluid

are connected together at the bottom, via a small pipe,

then fluid will flow under gravity,

from one

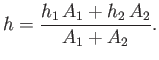

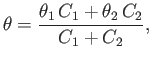

to the other, until the two heights are the same. The final height is easily

calculated by equating the total fluid volume in the initial and final

states. Thus,

.]

If two containers, filled to different heights,

with a free-flowing incompressible fluid

are connected together at the bottom, via a small pipe,

then fluid will flow under gravity,

from one

to the other, until the two heights are the same. The final height is easily

calculated by equating the total fluid volume in the initial and final

states. Thus,

| (4.1) |

|

(4.2) |

| (4.3) |

|

(4.4) |

The analogy between heat flow and fluid flow works because, in Lavoisier's theory, heat is a conserved quantity, just like the volume of an incompressible fluid. In fact, Lavoisier postulated that heat was an element. Note that atoms were thought to be indestructible before nuclear reactions were discovered, so the total amount of each element in the cosmos was assumed to be a constant. Thus, if Lavoisier had cared to formulate a law of thermodynamics from his calorific theory then he would have said that the total amount of heat in the universe was a constant.

In 1798, Benjamin Thompson, an Englishman who spent his early years in

pre-revolutionary

America, was minister for war and police in the German state of Bavaria.

One of his jobs was to oversee the boring of cannons in the state arsenal.

Thompson was struck by the

enormous, and seemingly inexhaustible, amount of heat generated in this process.

He simply could not understand where all this

heat was coming from. According to Lavoisier's calorific theory, the heat

must flow into the cannon from its immediate surroundings, which should, therefore,

become colder.

The flow should also eventually cease when all of the available heat has been

extracted.

In fact, Thompson observed that the surroundings of the cannon

got hotter, not colder,

and that the heating process continued unabated as long as the

boring machine was operating. Thompson postulated that some of the mechanical

work done

on the cannon by the boring machine was being converted into heat. At the time,

this was quite a revolutionary concept, and most people were not ready to accept it.

This is somewhat surprising, because, by the end of the eighteenth century,

the conversion of heat into

work, by steam engines, was quite commonplace.

Nevertheless, the conversion of work into heat did not gain broad acceptance until

1849, when an English physicist called

James Prescott Joule published the results of a long and

painstaking series of experiments. Joule confirmed that work could indeed

be converted

into heat. Moreover, he found that the same amount of work always generates

the same quantity of

heat. This is

true regardless of the nature of the work (e.g., mechanical, electrical,

et cetera). Joule was able to formulate what became known as

the work equivalent of heat.

Namely, that 1 newton meter of work is equivalent to ![]() calories of heat.

A calorie is the amount of heat required to raise the temperature of 1 gram of

water by 1 degree centigrade. Nowadays, we measure both heat and work using the

same units, so that one newton meter, or joule, of work is equivalent to

one joule of heat.

calories of heat.

A calorie is the amount of heat required to raise the temperature of 1 gram of

water by 1 degree centigrade. Nowadays, we measure both heat and work using the

same units, so that one newton meter, or joule, of work is equivalent to

one joule of heat.

In 1850, the German physicist Clausius correctly postulated that the essential conserved quantity is neither heat nor work, but some combination of the two which quickly became known as energy, from the Greek energeia meaning ``activity" or ``action.'' According to Clausius, the change in the internal energy of a macroscopic body can be written

| (4.5) |