Next: Exercises

Up: Quantum Dynamics

Previous: Gauge Transformations in Electromagnetism

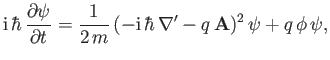

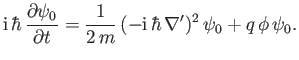

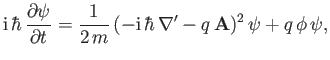

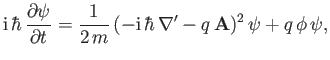

Consider a situation in which the electric and magnetic fields are non-time-varying. In this case,

Equation (3.89) becomes

|

(3.103) |

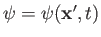

where

,

,

, and

, and

. The

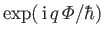

previous equation has the formal solution

. The

previous equation has the formal solution

|

(3.104) |

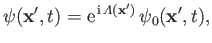

where

|

(3.105) |

and

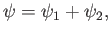

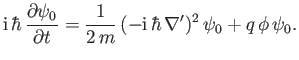

is a solution of

is a solution of

|

(3.106) |

Here,

is an arbitrary fixed point. However, the solution (3.104) only makes sense in a

region in which

is an arbitrary fixed point. However, the solution (3.104) only makes sense in a

region in which

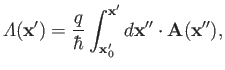

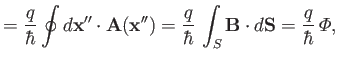

. To see this, let us imagine calculating the phase factor

. To see this, let us imagine calculating the phase factor

by evaluating the line integral specified in Equation (3.105) along two different paths, labelled 1 and 2, that join the

points

by evaluating the line integral specified in Equation (3.105) along two different paths, labelled 1 and 2, that join the

points

and

and  . We find that

. We find that

where

is the magnetic flux passing through a surface spanning the two paths. Here, we have

made use of the curl theorem [92], as well as Equation (3.73). Thus, the

phase factor

is the magnetic flux passing through a surface spanning the two paths. Here, we have

made use of the curl theorem [92], as well as Equation (3.73). Thus, the

phase factor

is only independent of the choice of path in the line integral when

is only independent of the choice of path in the line integral when

. Such independence is required if we insist that the wavefunction

be single valued.

. Such independence is required if we insist that the wavefunction

be single valued.

Suppose that a charged particle moves in a magnetic-field-free region that is not simply connected, but surrounds a

hole through which the magnetic flux

passes. Upon completing a circuit around the hole, the

particle's wavefunction is multiplied by

passes. Upon completing a circuit around the hole, the

particle's wavefunction is multiplied by

. The requirement that the wavefunction be

single-valued, and, hence, that the multiplication factor be unity, implies that the enclosed magnetic flux is quantized.

In fact.

. The requirement that the wavefunction be

single-valued, and, hence, that the multiplication factor be unity, implies that the enclosed magnetic flux is quantized.

In fact.

|

(3.108) |

where  is an integer. This effect is known as flux quantization.

is an integer. This effect is known as flux quantization.

A situation like that just described arises in the motion of electrons in a superconducting ring through which a magnetic field passes. Incidentally, superconductors contain no internal magnetic fields because they expel magnetic flux--this

behavior is called the Meissner effect [72]. Experimentally, the magnetic flux passing through a

superconducting ring is found to satisfy

|

(3.109) |

where  is an integer, and

is an integer, and  the magnitude of the electron charge [27,33]. This result

is consistent with our present understanding of the phenomenon of superconductivity, according to which

the fundamental charge carriers are correlated electron pairs known as Cooper pairs [6].

the magnitude of the electron charge [27,33]. This result

is consistent with our present understanding of the phenomenon of superconductivity, according to which

the fundamental charge carriers are correlated electron pairs known as Cooper pairs [6].

Consider an electron interference experiment in which a small solenoid containing magnetic flux is placed directly behind the

slits of a two-slit interference apparatus. The interference pattern at the screen is due

to the superposition of two parts of the wavefunction,

|

(3.110) |

where  and

and  are the wavefunctions due to electrons that originate from the source, pass through the first and

second slits, respectively, and then strike the same point on the screen. When the solenoid is energized an additional phase shift

are the wavefunctions due to electrons that originate from the source, pass through the first and

second slits, respectively, and then strike the same point on the screen. When the solenoid is energized an additional phase shift

is introduced between

is introduced between  and

and  , where

, where

is the net flux passing through the solenoid. In other

words, the magnetic field internal to the solenoid affects the interference pattern seen on the screen, despite the

fact that neither electron beam ever directly experiences a magnetic field (because the field is internal to the

solenoid, and the two interfering beams are assumed to pass on either side of the solenoid.)

This phenomena is known as the Aharonov-Bohm effect [2], and has been observed experimentally [112].

is the net flux passing through the solenoid. In other

words, the magnetic field internal to the solenoid affects the interference pattern seen on the screen, despite the

fact that neither electron beam ever directly experiences a magnetic field (because the field is internal to the

solenoid, and the two interfering beams are assumed to pass on either side of the solenoid.)

This phenomena is known as the Aharonov-Bohm effect [2], and has been observed experimentally [112].

Next: Exercises

Up: Quantum Dynamics

Previous: Gauge Transformations in Electromagnetism

Richard Fitzpatrick

2016-01-22

![$\displaystyle = \frac{q}{\hbar}\left[\int_1 d{\bf x}''\cdot{\bf A}({\bf x}'')-\int_2 d{\bf x}''\cdot{\bf A}({\bf x}'')\right]$](img814.png)

![]() passes. Upon completing a circuit around the hole, the

particle's wavefunction is multiplied by

passes. Upon completing a circuit around the hole, the

particle's wavefunction is multiplied by

![]() . The requirement that the wavefunction be

single-valued, and, hence, that the multiplication factor be unity, implies that the enclosed magnetic flux is quantized.

In fact.

. The requirement that the wavefunction be

single-valued, and, hence, that the multiplication factor be unity, implies that the enclosed magnetic flux is quantized.

In fact.