Next: Cold-Plasma Equations Up: Plasma Fluid Theory Previous: Magnetized Limit Contents

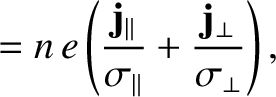

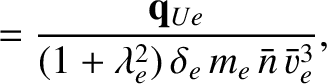

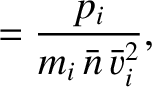

Let us consider a magnetized plasma. It is convenient to split the friction force

into a component

into a component  corresponding to resistivity, and a

component

corresponding to resistivity, and a

component  corresponding to the thermal force. Thus,

corresponding to the thermal force. Thus,

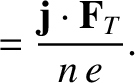

|

(4.119) |

|

|

(4.120) |

|

|

(4.121) |

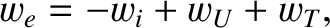

is split

into a component

is split

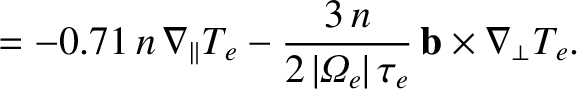

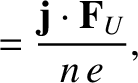

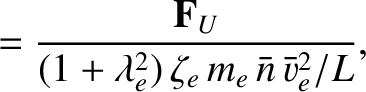

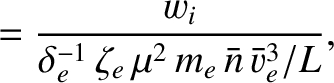

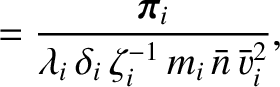

into a component  corresponding to the energy lost to the ions (in the

ion rest frame), a component

corresponding to the energy lost to the ions (in the

ion rest frame), a component  corresponding to work done by the friction

force

corresponding to work done by the friction

force  , and a component

, and a component  corresponding to work done by the

thermal force

corresponding to work done by the

thermal force  . Thus,

. Thus,

|

(4.122) |

|

|

(4.123) |

|

|

(4.124) |

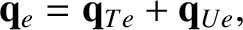

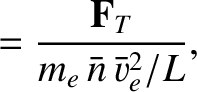

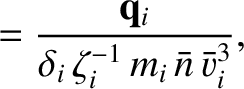

into

a diffusive component

into

a diffusive component

and a convective component

and a convective component

.

Thus,

.

Thus,

|

(4.125) |

|

|

(4.126) |

|

|

(4.127) |

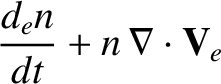

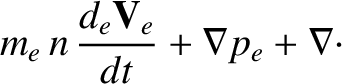

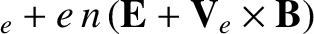

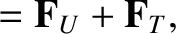

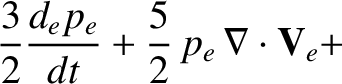

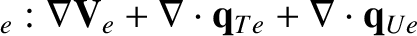

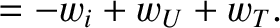

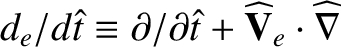

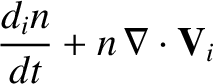

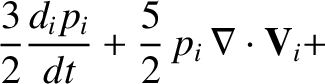

Let us, first of all, consider the electron fluid equations, which can be written:

|

|

(4.128) |

|

|

(4.129) |

|

|

(4.130) |

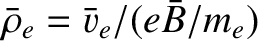

,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

and

,

and

, be typical values

of the particle density, the electron thermal velocity, the electron

mean-free-path, the magnetic field-strength, and the

electron gyroradius, respectively.

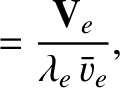

Suppose that the typical electron flow velocity is

, be typical values

of the particle density, the electron thermal velocity, the electron

mean-free-path, the magnetic field-strength, and the

electron gyroradius, respectively.

Suppose that the typical electron flow velocity is

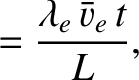

, and

the typical variation lengthscale is

, and

the typical variation lengthscale is  . Let

. Let

|

|

(4.131) |

|

|

(4.132) |

|

|

(4.133) |

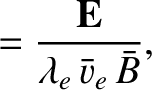

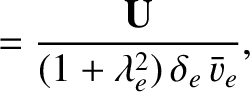

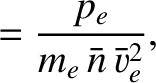

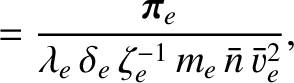

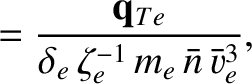

We define the following normalized quantities:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The normalization procedure is designed to make all hatted quantities

.

The normalization of the electric field is chosen

such that the

.

The normalization of the electric field is chosen

such that the

velocity is of similar magnitude to the electron fluid velocity. Note that the parallel viscosity

makes an

velocity is of similar magnitude to the electron fluid velocity. Note that the parallel viscosity

makes an

contribution to

contribution to

, whereas the gyroviscosity

makes an

, whereas the gyroviscosity

makes an

contribution, and the perpendicular viscosity only

makes an

contribution, and the perpendicular viscosity only

makes an

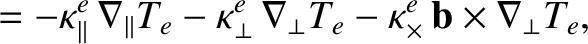

contribution. Likewise, the parallel thermal

conductivity

makes an

contribution. Likewise, the parallel thermal

conductivity

makes an

contribution to

contribution to

, whereas the cross

conductivity

makes an

, whereas the cross

conductivity

makes an

contribution, and the perpendicular conductivity only

makes an

contribution, and the perpendicular conductivity only

makes an

contribution. Similarly, the parallel components

of

contribution. Similarly, the parallel components

of  and

and

are

are

, whereas the perpendicular

components are

, whereas the perpendicular

components are

.

.

The normalized electron fluid equations take the form:

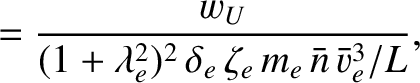

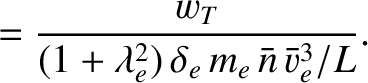

The only large or small (compared to unity) quantities in these equations are the parameters ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  .

Here,

.

Here,

. It is assumed that

. It is assumed that

.

.

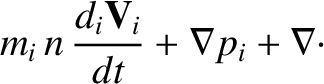

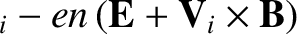

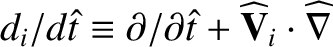

Let us now consider the ion fluid equations, which can be written:

|

|

(4.137) |

|

|

(4.138) |

|

|

(4.139) |

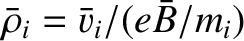

,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

and

,

and

, be typical values

of the particle density, the ion thermal velocity, the ion

mean-free-path, the magnetic field-strength, and the

ion gyroradius, respectively.

Suppose that the typical ion flow velocity is

, be typical values

of the particle density, the ion thermal velocity, the ion

mean-free-path, the magnetic field-strength, and the

ion gyroradius, respectively.

Suppose that the typical ion flow velocity is

, and

the typical variation lengthscale is

, and

the typical variation lengthscale is  . Let

. Let

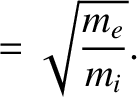

|

|

(4.140) |

|

|

(4.141) |

|

|

(4.142) |

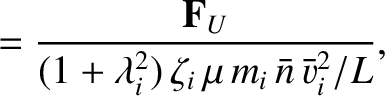

We define the following normalized quantities:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

As before, the normalization procedure is designed to make all hatted quantities

.

The normalization of the electric field is chosen

such that the

.

The normalization of the electric field is chosen

such that the

velocity is of similar magnitude to the ion fluid velocity. Note that the parallel viscosity

makes an

velocity is of similar magnitude to the ion fluid velocity. Note that the parallel viscosity

makes an

contribution to

contribution to

, whereas the gyroviscosity

makes an

, whereas the gyroviscosity

makes an

contribution, and the perpendicular viscosity only

makes an

contribution, and the perpendicular viscosity only

makes an

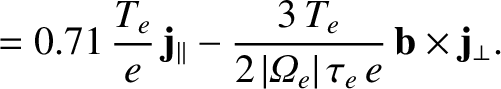

contribution. Likewise, the parallel thermal

conductivity

makes an

contribution. Likewise, the parallel thermal

conductivity

makes an

contribution to

contribution to

, whereas the cross

conductivity

makes an

, whereas the cross

conductivity

makes an

contribution, and the perpendicular conductivity only

makes an

contribution, and the perpendicular conductivity only

makes an

contribution. Similarly, the parallel component

of

contribution. Similarly, the parallel component

of  is

is

, whereas the perpendicular

component is

, whereas the perpendicular

component is

.

.

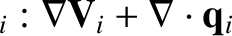

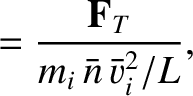

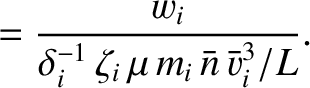

The normalized ion fluid equations take the form:

The only large or small (compared to unity) quantities in these equations are the parameters ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  .

Here,

.

Here,

.

.

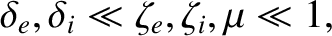

Let us adopt the ordering

|

(4.146) |

and

and  as small parameters, and

as small parameters, and  ,

,  , and

, and  as

as

.

In the second stage, we shall take note of the smallness of

.

In the second stage, we shall take note of the smallness of

,

,  , and

, and  . Note that the parameters

. Note that the parameters  and

and  are “free ranging." In other words, they can be either large, small, or

are “free ranging." In other words, they can be either large, small, or

.

In the initial stage of the

ordering procedure, the ion and electron

normalization schemes we have adopted become essentially

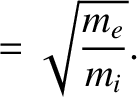

identical [because

.

In the initial stage of the

ordering procedure, the ion and electron

normalization schemes we have adopted become essentially

identical [because

], and

it is convenient to write

], and

it is convenient to write

|

|

(4.147) |

|

|

(4.148) |

|

|

(4.149) |

|

|

(4.150) |

|

|

(4.151) |

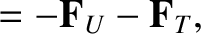

There are three fundamental orderings in plasma fluid theory.

The first fundamental ordering is

This corresponds to In other words, the fluid velocities are much greater than the respective thermal velocities. We also have Here, is conventionally termed the transit frequency, and is

the frequency with which fluid elements traverse the system. It is clear

that the transit frequencies are of approximately the same magnitudes as the gyrofrequencies

in this ordering. Keeping only the largest terms in Equations (4.134)–(4.136) and

(4.143)–(4.145), the Braginskii equations reduce to (in unnormalized form):

and

The factors in square brackets are just to remind us that the terms they precede

are smaller than the other terms in the equations (by the

corresponding factors inside

the

brackets).

is conventionally termed the transit frequency, and is

the frequency with which fluid elements traverse the system. It is clear

that the transit frequencies are of approximately the same magnitudes as the gyrofrequencies

in this ordering. Keeping only the largest terms in Equations (4.134)–(4.136) and

(4.143)–(4.145), the Braginskii equations reduce to (in unnormalized form):

and

The factors in square brackets are just to remind us that the terms they precede

are smaller than the other terms in the equations (by the

corresponding factors inside

the

brackets).

Equations (4.155)–(4.156) and (4.157)–(4.158) are called the cold-plasma equations, because

they can be obtained from the Braginskii equations by formally taking the

limit

. Likewise, the ordering (4.152) is called

the cold-plasma approximation. The cold-plasma approximation

applies not only to cold plasmas, but also to very fast disturbances that

propagate through conventional plasmas. In particular,

the cold-plasma equations provide a good description of the propagation

of electromagnetic waves through plasmas. After all, electromagnetic

waves generally have very high velocities (i.e.,

. Likewise, the ordering (4.152) is called

the cold-plasma approximation. The cold-plasma approximation

applies not only to cold plasmas, but also to very fast disturbances that

propagate through conventional plasmas. In particular,

the cold-plasma equations provide a good description of the propagation

of electromagnetic waves through plasmas. After all, electromagnetic

waves generally have very high velocities (i.e.,  ),

which they impart to

plasma fluid elements, so there is usually

no difficulty satisfying the inequality (4.153).

),

which they impart to

plasma fluid elements, so there is usually

no difficulty satisfying the inequality (4.153).

The electron and ion pressures can be neglected in the cold-plasma limit, because the thermal velocities are much smaller than the fluid velocities. It follows that there is no need for an electron or ion energy evolution equation. Furthermore, the motion of the plasma is so fast, in this limit, that relatively slow “transport” effects, such as viscosity and thermal conductivity, play no role in the cold-plasma fluid equations. In fact, the only collisional effect that appears in these equations is resistivity.

The second fundamental ordering is

which corresponds to |

(4.160) |

Equations (4.161)–(4.163) and (4.164)–(4.165) are called the magnetohydrodynamical equations, or MHD equations, for short. Likewise, the ordering (4.159) is called the MHD approximation. The MHD equations are conventionally used to study macroscopic plasma instabilities possessing relatively fast growth-rates: for example, “sausage” modes and “kink” modes (Bateman 1978).

The electron and ion pressures cannot be neglected in the MHD limit, because the fluid velocities are similar in magnitude to the respective thermal velocities. Thus, electron and ion energy evolution equations are needed in this limit. However, MHD motion is sufficiently fast that “transport” effects, such as viscosity and thermal conductivity, are too slow to play a role in the MHD equations. In fact, the only collisional effects that appear in these equations are resistivity, the thermal force, and electron-ion collisional energy exchange.

The third fundamental ordering is

which corresponds to |

(4.168) |

is a typical drift (e.g., a curvature or grad-B

drift—see Chapter 2) velocity. In other words, the fluid velocities

are of similar magnitude to the respective drift velocities. Keeping only the

largest terms in Equations (3.113) and (3.116), the Braginskii equations reduce to

(in unnormalized form):

and

As before, the factors in square brackets remind us that the terms they

precede are larger, or smaller, than the other terms in the equations.

is a typical drift (e.g., a curvature or grad-B

drift—see Chapter 2) velocity. In other words, the fluid velocities

are of similar magnitude to the respective drift velocities. Keeping only the

largest terms in Equations (3.113) and (3.116), the Braginskii equations reduce to

(in unnormalized form):

and

As before, the factors in square brackets remind us that the terms they

precede are larger, or smaller, than the other terms in the equations.

Equations (4.169)–(4.171) and (4.172)–(4.174) are called the drift equations. Likewise, the ordering (4.167) is called the drift approximation. The drift equations are conventionally used to study equilibrium evolution, and the slow growing “micro-instabilities” that are responsible for turbulent transport in tokamaks. It is clear that virtually all of the original terms in the Braginskii equations must be retained in this limit.

In the following sections, we investigate the cold-plasma equations, the MHD equations, and the drift equations, in more detail.