Next: Plasma Beta Up: Plasma Parameters Previous: Collisions Contents

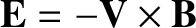

, is strong enough to significantly alter particle

trajectories. In particular,

magnetized plasmas are highly anisotropic, responding differently to

forces that are parallel and perpendicular to the direction

of

, is strong enough to significantly alter particle

trajectories. In particular,

magnetized plasmas are highly anisotropic, responding differently to

forces that are parallel and perpendicular to the direction

of  . Incidentally, a magnetized plasma moving with

mean velocity

. Incidentally, a magnetized plasma moving with

mean velocity  contains an electric field

contains an electric field

that is not affected

by Debye shielding. Of course, the electric

field is essentially zero in the rest frame of the plasma.

that is not affected

by Debye shielding. Of course, the electric

field is essentially zero in the rest frame of the plasma.

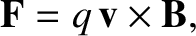

As is well known, charged particles respond to the Lorentz force,

|

(1.28) |

, while executing

circular Larmor orbits, or gyro-orbits, in the plane perpendicular to

, while executing

circular Larmor orbits, or gyro-orbits, in the plane perpendicular to  (Fitzpatrick 2008).

As the field-strength increases, the resulting helical orbits become more

tightly wound, effectively tying particles to magnetic field-lines.

(Fitzpatrick 2008).

As the field-strength increases, the resulting helical orbits become more

tightly wound, effectively tying particles to magnetic field-lines.

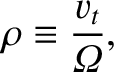

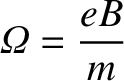

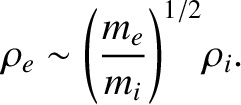

The typical Larmor radius, or gyroradius, of a charged particle gyrating in a magnetic field is given by

|

(1.29) |

|

(1.30) |

|

(1.31) |

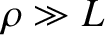

A plasma system, or process, is said to be magnetized if its

characteristic lengthscale,  , is large compared to the gyroradius.

In the opposite limit,

, is large compared to the gyroradius.

In the opposite limit,  , charged particles have essentially

straight-line trajectories. Thus, the ability of the magnetic field to

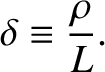

significantly affect particle trajectories is measured by the

magnetization parameter,

, charged particles have essentially

straight-line trajectories. Thus, the ability of the magnetic field to

significantly affect particle trajectories is measured by the

magnetization parameter,

|

(1.32) |

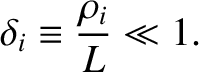

There are some cases of interest in which the electrons are magnetized, but the ions are not. However, a “magnetized” plasma conventionally refers to one in which both species are magnetized. This state is generally achieved when

|

(1.33) |