Next: Cutoffs Up: Waves in Inhomogeneous Plasmas Previous: Introduction Contents

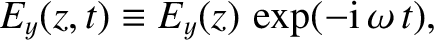

, propagating along the

, propagating along the  -axis in an unmagnetized plasma

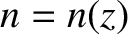

whose refractive index,

-axis in an unmagnetized plasma

whose refractive index,  , is a function of

, is a function of  . Let us assume that

the wave normal is initially aligned along the

. Let us assume that

the wave normal is initially aligned along the  -axis, and, furthermore, that

the wave starts off polarized in the

-axis, and, furthermore, that

the wave starts off polarized in the  -direction. It is

easily demonstrated that the wave normal subsequently remains aligned along

the

-direction. It is

easily demonstrated that the wave normal subsequently remains aligned along

the  -axis, and also that the polarization

state does not change.

Thus, the wave is fully described by

-axis, and also that the polarization

state does not change.

Thus, the wave is fully described by

|

(6.1) |

|

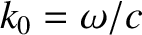

(6.2) |

and

and  satisfy

the differential equations

and

respectively. Here,

satisfy

the differential equations

and

respectively. Here,

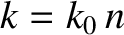

is the wavenumber

in free space. Of course, the actual wavenumber is

is the wavenumber

in free space. Of course, the actual wavenumber is  .

.

The solution of Equation (6.3) for the case of a homogeneous plasma, for which

is constant, is simply

is constant, is simply

is a constant, and

The solution (6.5)

represents a wave of constant amplitude

is a constant, and

The solution (6.5)

represents a wave of constant amplitude  , and phase

, and phase  . According to

Equation (6.6),

there are two independent waves that can propagate through the plasma.

The upper sign corresponds to a wave that propagates in the

. According to

Equation (6.6),

there are two independent waves that can propagate through the plasma.

The upper sign corresponds to a wave that propagates in the  -direction,

whereas the lower sign corresponds to a wave that propagates in the

-direction,

whereas the lower sign corresponds to a wave that propagates in the

-direction. Both waves propagate at the constant phase-velocity

-direction. Both waves propagate at the constant phase-velocity  .

.

In general, if  then the solution of Equation (6.3) does not remotely resemble

the wave-like solution (6.5). However, in the limit in which

then the solution of Equation (6.3) does not remotely resemble

the wave-like solution (6.5). However, in the limit in which  is

a “slowly varying” function of

is

a “slowly varying” function of  (exactly how slowly varying is something that

will be established later on), we expect to recover wave-like solutions.

Let us suppose that

(exactly how slowly varying is something that

will be established later on), we expect to recover wave-like solutions.

Let us suppose that  is indeed a “slowly varying” function, and let us try

substituting the wave-like solution (6.5) into Equation (6.3). We obtain

is indeed a “slowly varying” function, and let us try

substituting the wave-like solution (6.5) into Equation (6.3). We obtain

is a constant then

is a constant then

.

It is, therefore, reasonable to suppose that if

.

It is, therefore, reasonable to suppose that if  is a “slowly varying” function

then the last term on the right-hand side of the previous equation is relatively small. Thus, to a first approximation, Equation (6.7) yields

is a “slowly varying” function

then the last term on the right-hand side of the previous equation is relatively small. Thus, to a first approximation, Equation (6.7) yields

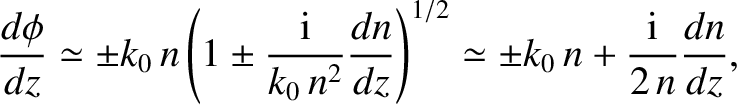

|

(6.8) |

can

be regarded as a “slowly varying” function of

can

be regarded as a “slowly varying” function of  [i.e., the second term on the right-hand side of Equation (6.7) is

negligible compared to the first] as long as

[i.e., the second term on the right-hand side of Equation (6.7) is

negligible compared to the first] as long as

.

In other words, the approximation holds provided that the variation

lengthscale of the refractive index is far longer than the wavelength of the wave.

.

In other words, the approximation holds provided that the variation

lengthscale of the refractive index is far longer than the wavelength of the wave.

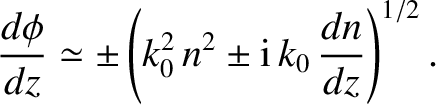

The second approximation to the solution is obtained by substituting Equation (6.9) into the right-hand side of Equation (6.7):

|

(6.10) |

|

(6.11) |

|

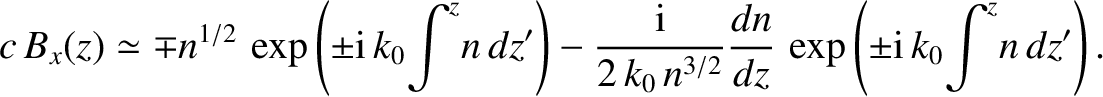

(6.14) |

We can test to what extent expression (6.13) is a good solution of Equation (6.3) by substituting this expression into the left-hand side of the equation. The result is

![$\displaystyle \frac{1}{n^{1/2}}\left[ \frac{3}{4}\left(\frac{1}{n}

\frac{dn}{dz...

...\frac{1}{n}

\frac{dn}{dz}\right)^2 -\frac{1}{2\,n}\frac{d^2 n}{dz^2}\right]E_y.$](img1937.png) |

||

| (6.15) |

. Hence, the

condition for Equation (6.13) to be a good solution of Equation (6.3)

becomes

. Hence, the

condition for Equation (6.13) to be a good solution of Equation (6.3)

becomes

The solutions

to the non-uniform wave equations (6.3) and (6.4) are usually referred to as WKB solutions, in honor of G. Wentzel (Wentzel 1926), H.A. Kramers (Kramers 1926), and L. Brillouin (Brilloiun 1926), who are credited with independently discovering these solutions (in a quantum mechanical context) in 1926. Actually, H. Jeffries (Jeffries 1924) wrote a paper on WKB solutions (in a wave propagation context) in 1924. Hence, these solutions are sometimes called the WKBJ solutions (or even the JWKB solutions). To be strictly accurate, the WKB solutions were first discussed by Liouville (Liouville 1837) and Green (Green 1837) in 1837, and again by Rayleigh (Rayleigh 1912) in 1912. In the following, we refer to Equations (6.17) and (6.18) as WKB solutions, because this is what they are most commonly called. However, it should be understood that, in doing so, we are not making any definitive statement as to the credit due to various scientists in discovering them. More information about WKB solutions can be found in the classic monograph of Heading (Heading 1962).

If a propagating wave is normally incident on an interface

at which the

refractive index suddenly changes (for instance, if a light

wave propagating through

air is normally incident on a glass slab) then there is generally

significant reflection of the wave (Fitzpatrick 2013). However, according to the WKB solutions,

(6.17) and (6.18), when a propagating wave is normally incident on a medium in which

the refractive index changes slowly along the direction of propagation of the

wave then the wave is not reflected at all. This is true

even if the refractive index

varies very substantially along the path of propagation of the wave,

as long as it varies sufficiently slowly. The WKB

solutions imply that, as the wave propagates through the medium, its wavelength

gradually changes. In fact, the wavelength at position  is approximately

is approximately

![$\lambda(z)= 2\pi/ [k_0\,n(z)]$](img1944.png) . Equations (6.17) and (6.18) also imply that the amplitude

of the wave gradually changes as it propagates. In fact, the amplitude of the electric

field component is inversely proportional to

. Equations (6.17) and (6.18) also imply that the amplitude

of the wave gradually changes as it propagates. In fact, the amplitude of the electric

field component is inversely proportional to  , whereas the amplitude of the

magnetic field component is directly proportional to

, whereas the amplitude of the

magnetic field component is directly proportional to  .

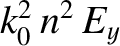

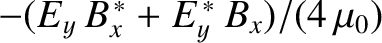

Note, however, that the energy

flux in the

.

Note, however, that the energy

flux in the  -direction, which is given by the the Poynting vector

-direction, which is given by the the Poynting vector

, remains constant (assuming that

, remains constant (assuming that  is predominately

real).

is predominately

real).

Of course, the WKB solutions (6.17) and (6.18) are only approximations. In reality,

a wave propagating through a medium in which the refractive index is a slowly

varying function of position is subject to a small amount of reflection.

However, it is easily demonstrated that the ratio of the reflected amplitude

to the incident amplitude is of order

(Budden 1985). Thus, as long as

the refractive index varies on a much longer lengthscale than the wavelength

of the radiation, the reflected wave is negligibly small. This conclusion remains

valid as long as the inequality (6.16) is satisfied.

This inequality obviously

breaks down in the vicinity of a point where

(Budden 1985). Thus, as long as

the refractive index varies on a much longer lengthscale than the wavelength

of the radiation, the reflected wave is negligibly small. This conclusion remains

valid as long as the inequality (6.16) is satisfied.

This inequality obviously

breaks down in the vicinity of a point where  . We would, therefore,

expect strong reflection of the incident wave from such a point.

Furthermore, the WKB solutions also break down at a

point where

. We would, therefore,

expect strong reflection of the incident wave from such a point.

Furthermore, the WKB solutions also break down at a

point where

, because the amplitude of

, because the amplitude of  becomes

infinite.

becomes

infinite.