Langmuir Sheaths

Virtually all terrestrial plasmas are contained within solid vacuum vessels. But, what happens to plasma in the immediate vicinity of a vessel wall? Actually, to a first approximation, when ions and electrons hit a solid surface they recombine and are lost to the plasma. Hence, we can

treat the wall as a perfect sink of particles. Now, given that the electrons in a plasma generally

move much faster than the ions, the initial electron flux into the wall greatly

exceeds the ion flux, assuming that the wall starts off

unbiased with respect to the plasma. Of course, this flux imbalance causes the wall to charge up negatively, and so

generates a potential barrier that repels the electrons, and thereby

reduces the electron flux.

Debye shielding

confines this barrier to a thin layer of plasma, whose thickness is a few

Debye lengths, coating the inside surface of the wall. This layer

is known as a plasma sheath or a Langmuir sheath.

The height of the potential barrier continues to grow as long

as there is a net flux of negative charge into the wall.

This process presumably comes to an end, and a steady-state is attained, when the potential barrier becomes sufficiently large to make electron flux equal to the ion flux (Hazeltine and Waelbroeck 2004).

Let us construct a one-dimensional model of an unmagnetized, steady-state, Langmuir sheath.

Suppose that the wall lies at  , and that the plasma occupies the

region

, and that the plasma occupies the

region  . Let us treat the ions and the electrons inside the sheath

as collisionless fluids.

The ion and electron equations of

motion are thus written

. Let us treat the ions and the electrons inside the sheath

as collisionless fluids.

The ion and electron equations of

motion are thus written

respectively. Here,

is the electrostatic potential. Moreover, we have

assumed uniform ion and electron temperatures,

is the electrostatic potential. Moreover, we have

assumed uniform ion and electron temperatures,  and

and  ,

respectively, for the sake of simplicity. We have also neglected any off-diagonal

terms in the ion and electron stress-tensors, because these terms are

comparatively small.

Note that quasi-neutrality

does not apply inside the sheath, and so the ion and

electron number densities,

,

respectively, for the sake of simplicity. We have also neglected any off-diagonal

terms in the ion and electron stress-tensors, because these terms are

comparatively small.

Note that quasi-neutrality

does not apply inside the sheath, and so the ion and

electron number densities,  and

and  , respectively, are not

necessarily equal to one another.

, respectively, are not

necessarily equal to one another.

Consider the ion fluid. Let us assume that the mean ion velocity,  ,

is much greater than the ion thermal velocity,

,

is much greater than the ion thermal velocity,

. Because,

as will become apparent,

. Because,

as will become apparent,

, this ordering necessarily implies

that

, this ordering necessarily implies

that

: that is, that the ions are

cold with respect to the electrons. It turns out that plasmas in the

immediate vicinity of solid walls often have comparatively cold ions, so our ordering assumption

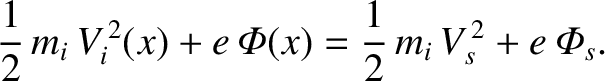

is fairly reasonable. In the cold ion limit, the pressure term in Equation (4.243)

is negligible, and the equation can be integrated to

give

: that is, that the ions are

cold with respect to the electrons. It turns out that plasmas in the

immediate vicinity of solid walls often have comparatively cold ions, so our ordering assumption

is fairly reasonable. In the cold ion limit, the pressure term in Equation (4.243)

is negligible, and the equation can be integrated to

give

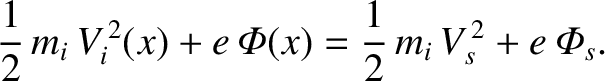

|

(4.245) |

Here,  and

and

are the mean ion velocity and electrostatic

potential, respectively, at the edge of the sheath (i.e.,

are the mean ion velocity and electrostatic

potential, respectively, at the edge of the sheath (i.e.,

).

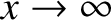

Now, ion fluid continuity requires that

).

Now, ion fluid continuity requires that

|

(4.246) |

where  is the ion number density at the sheath boundary. Incidentally, because we

expect quasi-neutrality to hold in the plasma outside the sheath, the electron number density

at the edge of the sheath must also be

is the ion number density at the sheath boundary. Incidentally, because we

expect quasi-neutrality to hold in the plasma outside the sheath, the electron number density

at the edge of the sheath must also be  (assuming singly-charged

ions). The previous two equations can be combined to give

(assuming singly-charged

ions). The previous two equations can be combined to give

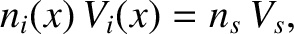

Consider the electron fluid. Let us assume that the mean electron

velocity,  , is much less than the electron thermal

velocity,

, is much less than the electron thermal

velocity,

. In fact, this must be the case, otherwise,

the electron flux to the wall would greatly exceed the ion flux.

Now, if the electron fluid is essentially stationary then the left-hand side of

Equation (4.244) is negligible, and the equation can be integrated to

give

. In fact, this must be the case, otherwise,

the electron flux to the wall would greatly exceed the ion flux.

Now, if the electron fluid is essentially stationary then the left-hand side of

Equation (4.244) is negligible, and the equation can be integrated to

give

![$\displaystyle n_e = n_s\,\exp\left[\frac{e\,({\mit\Phi}-{\mit\Phi}_s)}{T_e}\right].$](img1573.png) |

(4.249) |

Here, we have made use of the fact that  at

the edge of the sheath.

at

the edge of the sheath.

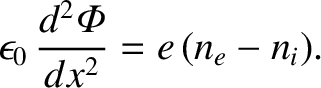

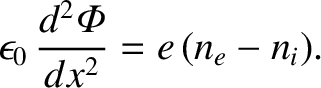

Poisson's equation is written

|

(4.250) |

It follows that

![$\displaystyle \epsilon_0\,\frac{d^2{\mit\Phi}}{dx^2}= e\,n_s\left(\exp\left[\fr...

...1- \frac{2\,e}{m_i\,V_s^{\,2}}\,({\mit\Phi}-{\mit\Phi}_s)\right]^{-1/2}\right).$](img1576.png) |

(4.251) |

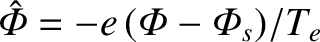

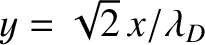

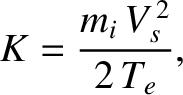

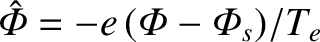

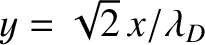

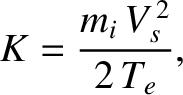

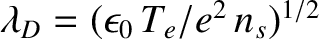

Let

,

,

, and

, and

|

(4.252) |

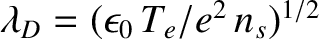

where

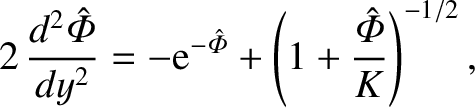

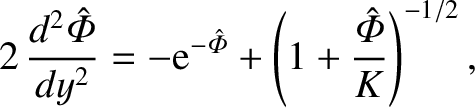

is the Debye length. Equation (4.251) transforms to

is the Debye length. Equation (4.251) transforms to

|

(4.253) |

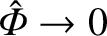

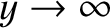

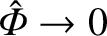

subject to the boundary condition

as

as

.

Multiplying through by

.

Multiplying through by

, integrating with respect to

, integrating with respect to  , and making use of the

boundary condition, we obtain

, and making use of the

boundary condition, we obtain

![$\displaystyle \left(\frac{d\skew{3}\hat{\mit\Phi}}{dy}\right)^2 = {\rm e}^{-\sk...

...}-1+ 2\,K\left[

\left(1+\frac{\skew{3}\hat{\mit\Phi}}{K}\right)^{1/2}-1\right].$](img1585.png) |

(4.254) |

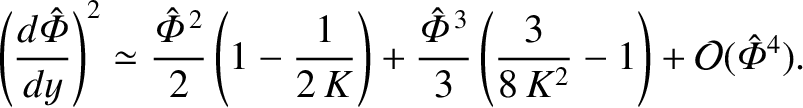

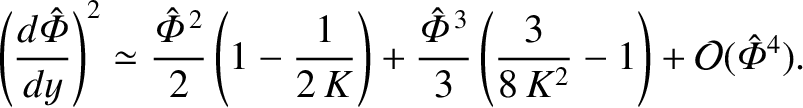

Unfortunately, the previous equation is highly nonlinear, and can only be solved numerically.

However, it is not necessary to attempt this to see that

a physical solution can only exist

if the right-hand side of the equation is positive for all  . Consider the

limit

. Consider the

limit

. It follows from the boundary condition that

. It follows from the boundary condition that

. Expanding

the right-hand side of Equation (4.254) in powers of

. Expanding

the right-hand side of Equation (4.254) in powers of

, we find that the zeroth- and first-order terms cancel, and we are left with

, we find that the zeroth- and first-order terms cancel, and we are left with

|

(4.255) |

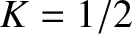

Now, the purpose of the sheath is to shield the plasma from the wall

potential. It can be seen, from the previous expression, that the physical

solution with

maximum possible shielding corresponds to  , because this

choice eliminates the first term on the right-hand side (thereby making

, because this

choice eliminates the first term on the right-hand side (thereby making

as small as possible at large

as small as possible at large  ) leaving the much smaller,

but positive (note that

) leaving the much smaller,

but positive (note that

is positive), second term.

Hence, we conclude that

is positive), second term.

Hence, we conclude that

|

(4.256) |

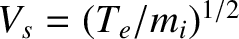

This result is known as the Bohm sheath criterion.

It is a somewhat surprising result, because it indicates that

ions at the edge of the sheath are already moving toward the wall at a

considerable velocity. Of course, the ions are further accelerated

as they pass through the sheath. Because the ions are presumably at

rest in the interior of the plasma, it is clear that there

must exist a region sandwiched between the sheath and the main plasma

in which the ions are accelerated from rest to the Bohm velocity,

. This region is called the pre-sheath,

and is both quasi-neutral and much wider than the sheath (the actual

width depends on the nature of the ion source).

. This region is called the pre-sheath,

and is both quasi-neutral and much wider than the sheath (the actual

width depends on the nature of the ion source).

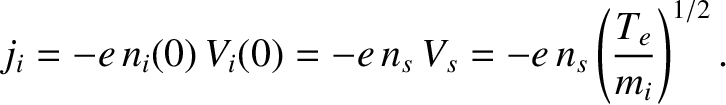

The ion current density at the wall is

|

(4.257) |

This current density is negative because the ions are moving in the negative  -direction. What about the electron current density? Well, the

number density of electrons at the wall is

-direction. What about the electron current density? Well, the

number density of electrons at the wall is

![$n_e(0) = n_s\,\exp[\,e\,({\mit\Phi}_w-{\mit\Phi}_s)/T_e)]$](img1593.png) , where

, where

is the wall potential. Let us assume

that the electrons have a Maxwellian velocity distribution peaked at

zero velocity (because the electron fluid velocity is much less than the

electron thermal velocity). It follows that half of the electrons at

is the wall potential. Let us assume

that the electrons have a Maxwellian velocity distribution peaked at

zero velocity (because the electron fluid velocity is much less than the

electron thermal velocity). It follows that half of the electrons at  are moving in

the negative-

are moving in

the negative- direction, and half in the positive-

direction, and half in the positive- direction.

Of course, the former electrons hit the wall, and thereby constitute an electron

current to the wall. This current is

direction.

Of course, the former electrons hit the wall, and thereby constitute an electron

current to the wall. This current is

, where

the

, where

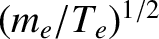

the  comes from averaging over solid angle, and

comes from averaging over solid angle, and

is the mean electron speed corresponding to a

Maxwellian velocity distribution (Reif 1965). Thus, the electron current density at the wall

is

is the mean electron speed corresponding to a

Maxwellian velocity distribution (Reif 1965). Thus, the electron current density at the wall

is

![$\displaystyle j_e= e\,n_s\,\left(\frac{T_e}{2\pi\,m_e}\right)^{1/2} \exp\left[\frac{e\,({\mit\Phi}_w-{\mit\Phi}_s)}{T_e}\right].$](img1598.png) |

(4.258) |

In order to replace the electrons lost to the wall, the electrons must have a mean velocity

![$\displaystyle V_{e\,s} = \frac{j_e}{e\,n_s}= \left(\frac{T_e}{2\pi\,m_e}\right)^{1/2} \exp\left[\frac{e\,({\mit\Phi}_w-{\mit\Phi}_s)}{T_e}\right]$](img1599.png) |

(4.259) |

at the edge of the sheath. However, we previously assumed that any

electron fluid velocity was much less than the electron thermal

velocity,

. As is clear from the previous equation,

this is only possible provided that

. As is clear from the previous equation,

this is only possible provided that

![$\displaystyle \exp\left[\frac{e\,({\mit\Phi}_w-{\mit\Phi}_s)}{T_e}\right]\ll 1:$](img1601.png) |

(4.260) |

that is, provided that the wall potential is sufficiently negative to

strongly reduce the electron number density at the wall.

The net current density at the wall is

![$\displaystyle j = e\,n_s\,\left(\frac{T_e}{m_i}\right)^{1/2}\left(\left[\frac{m...

...ght]^{1/2}\exp\left[\frac{e\,({\mit\Phi}_w-{\mit\Phi}_s)}{T_e}\right]-1\right).$](img1602.png) |

(4.261) |

Of course, we require  in a steady-state sheath, in order to prevent wall charging, and so we obtain

in a steady-state sheath, in order to prevent wall charging, and so we obtain

|

(4.262) |

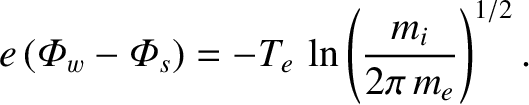

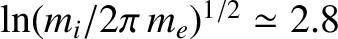

We conclude that, in a steady-state sheath, the wall is biased negatively with respect to the

sheath edge by an amount that is proportional to the electron temperature.

Figure 4.4:

Langmuir sheath in a hydrogen plasma.

|

|

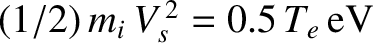

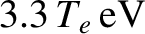

For a hydrogen plasma,

. Thus, hydrogen

ions enter the sheath with an initial energy

. Thus, hydrogen

ions enter the sheath with an initial energy

, fall through the sheath potential, and so impact the

wall with energy

, fall through the sheath potential, and so impact the

wall with energy

.

.

Combining Equations (4.247)–(4.249), (4.254), (4.262), and making use of the

constraint  , we arrive at the following set of equations that characterize the structure of a

Langmuir sheath:

, we arrive at the following set of equations that characterize the structure of a

Langmuir sheath:

Equation (4.263) can be solved numerically, subject to the boundary condition (4.264), to

give the results summarized in Figure 4.4. The figure illustrates how the deviation from quasi-neutrality within the

sheath generates an electric potential that greatly reduces the electron number density at the wall, and also

accelerates the ions as they pass through the sheath (toward the wall).

, and that the plasma occupies the

region

, and that the plasma occupies the

region  . Let us treat the ions and the electrons inside the sheath

as collisionless fluids.

The ion and electron equations of

motion are thus written

. Let us treat the ions and the electrons inside the sheath

as collisionless fluids.

The ion and electron equations of

motion are thus written

is the electrostatic potential. Moreover, we have

assumed uniform ion and electron temperatures,

is the electrostatic potential. Moreover, we have

assumed uniform ion and electron temperatures,  and

and  ,

respectively, for the sake of simplicity. We have also neglected any off-diagonal

terms in the ion and electron stress-tensors, because these terms are

comparatively small.

Note that quasi-neutrality

does not apply inside the sheath, and so the ion and

electron number densities,

,

respectively, for the sake of simplicity. We have also neglected any off-diagonal

terms in the ion and electron stress-tensors, because these terms are

comparatively small.

Note that quasi-neutrality

does not apply inside the sheath, and so the ion and

electron number densities,  and

and  , respectively, are not

necessarily equal to one another.

, respectively, are not

necessarily equal to one another.

,

is much greater than the ion thermal velocity,

,

is much greater than the ion thermal velocity,

. Because,

as will become apparent,

. Because,

as will become apparent,

, this ordering necessarily implies

that

, this ordering necessarily implies

that

: that is, that the ions are

cold with respect to the electrons. It turns out that plasmas in the

immediate vicinity of solid walls often have comparatively cold ions, so our ordering assumption

is fairly reasonable. In the cold ion limit, the pressure term in Equation (4.243)

is negligible, and the equation can be integrated to

give

: that is, that the ions are

cold with respect to the electrons. It turns out that plasmas in the

immediate vicinity of solid walls often have comparatively cold ions, so our ordering assumption

is fairly reasonable. In the cold ion limit, the pressure term in Equation (4.243)

is negligible, and the equation can be integrated to

give

and

and

are the mean ion velocity and electrostatic

potential, respectively, at the edge of the sheath (i.e.,

are the mean ion velocity and electrostatic

potential, respectively, at the edge of the sheath (i.e.,

).

Now, ion fluid continuity requires that

).

Now, ion fluid continuity requires that

is the ion number density at the sheath boundary. Incidentally, because we

expect quasi-neutrality to hold in the plasma outside the sheath, the electron number density

at the edge of the sheath must also be

is the ion number density at the sheath boundary. Incidentally, because we

expect quasi-neutrality to hold in the plasma outside the sheath, the electron number density

at the edge of the sheath must also be  (assuming singly-charged

ions). The previous two equations can be combined to give

(assuming singly-charged

ions). The previous two equations can be combined to give

![$\displaystyle = V_s\left[1- \frac{2\,e}{m_i\,V_s^{\,2}}\,({\mit\Phi}-{\mit\Phi}_s)\right]^{1/2},$](img1569.png)

![$\displaystyle = n_s\left[1- \frac{2\,e}{m_i\,V_s^{\,2}}\,({\mit\Phi}-{\mit\Phi}_s)\right]^{-1/2}$](img1571.png)

, is much less than the electron thermal

velocity,

, is much less than the electron thermal

velocity,

. In fact, this must be the case, otherwise,

the electron flux to the wall would greatly exceed the ion flux.

Now, if the electron fluid is essentially stationary then the left-hand side of

Equation (4.244) is negligible, and the equation can be integrated to

give

. In fact, this must be the case, otherwise,

the electron flux to the wall would greatly exceed the ion flux.

Now, if the electron fluid is essentially stationary then the left-hand side of

Equation (4.244) is negligible, and the equation can be integrated to

give

at

the edge of the sheath.

at

the edge of the sheath.

,

,

, and

, and

is the Debye length. Equation (4.251) transforms to

is the Debye length. Equation (4.251) transforms to

as

as

.

Multiplying through by

.

Multiplying through by

, integrating with respect to

, integrating with respect to  , and making use of the

boundary condition, we obtain

Unfortunately, the previous equation is highly nonlinear, and can only be solved numerically.

However, it is not necessary to attempt this to see that

a physical solution can only exist

if the right-hand side of the equation is positive for all

, and making use of the

boundary condition, we obtain

Unfortunately, the previous equation is highly nonlinear, and can only be solved numerically.

However, it is not necessary to attempt this to see that

a physical solution can only exist

if the right-hand side of the equation is positive for all  . Consider the

limit

. Consider the

limit

. It follows from the boundary condition that

. It follows from the boundary condition that

. Expanding

the right-hand side of Equation (4.254) in powers of

. Expanding

the right-hand side of Equation (4.254) in powers of

, we find that the zeroth- and first-order terms cancel, and we are left with

, we find that the zeroth- and first-order terms cancel, and we are left with

, because this

choice eliminates the first term on the right-hand side (thereby making

, because this

choice eliminates the first term on the right-hand side (thereby making

as small as possible at large

as small as possible at large  ) leaving the much smaller,

but positive (note that

) leaving the much smaller,

but positive (note that

is positive), second term.

Hence, we conclude that

This result is known as the Bohm sheath criterion.

It is a somewhat surprising result, because it indicates that

ions at the edge of the sheath are already moving toward the wall at a

considerable velocity. Of course, the ions are further accelerated

as they pass through the sheath. Because the ions are presumably at

rest in the interior of the plasma, it is clear that there

must exist a region sandwiched between the sheath and the main plasma

in which the ions are accelerated from rest to the Bohm velocity,

is positive), second term.

Hence, we conclude that

This result is known as the Bohm sheath criterion.

It is a somewhat surprising result, because it indicates that

ions at the edge of the sheath are already moving toward the wall at a

considerable velocity. Of course, the ions are further accelerated

as they pass through the sheath. Because the ions are presumably at

rest in the interior of the plasma, it is clear that there

must exist a region sandwiched between the sheath and the main plasma

in which the ions are accelerated from rest to the Bohm velocity,

. This region is called the pre-sheath,

and is both quasi-neutral and much wider than the sheath (the actual

width depends on the nature of the ion source).

. This region is called the pre-sheath,

and is both quasi-neutral and much wider than the sheath (the actual

width depends on the nature of the ion source).

-direction. What about the electron current density? Well, the

number density of electrons at the wall is

-direction. What about the electron current density? Well, the

number density of electrons at the wall is

![$n_e(0) = n_s\,\exp[\,e\,({\mit\Phi}_w-{\mit\Phi}_s)/T_e)]$](img1593.png) , where

, where

is the wall potential. Let us assume

that the electrons have a Maxwellian velocity distribution peaked at

zero velocity (because the electron fluid velocity is much less than the

electron thermal velocity). It follows that half of the electrons at

is the wall potential. Let us assume

that the electrons have a Maxwellian velocity distribution peaked at

zero velocity (because the electron fluid velocity is much less than the

electron thermal velocity). It follows that half of the electrons at  are moving in

the negative-

are moving in

the negative- direction, and half in the positive-

direction, and half in the positive- direction.

Of course, the former electrons hit the wall, and thereby constitute an electron

current to the wall. This current is

direction.

Of course, the former electrons hit the wall, and thereby constitute an electron

current to the wall. This current is

, where

the

, where

the  comes from averaging over solid angle, and

comes from averaging over solid angle, and

is the mean electron speed corresponding to a

Maxwellian velocity distribution (Reif 1965). Thus, the electron current density at the wall

is

is the mean electron speed corresponding to a

Maxwellian velocity distribution (Reif 1965). Thus, the electron current density at the wall

is

![$\displaystyle j_e= e\,n_s\,\left(\frac{T_e}{2\pi\,m_e}\right)^{1/2} \exp\left[\frac{e\,({\mit\Phi}_w-{\mit\Phi}_s)}{T_e}\right].$](img1598.png)

![$\displaystyle V_{e\,s} = \frac{j_e}{e\,n_s}= \left(\frac{T_e}{2\pi\,m_e}\right)^{1/2} \exp\left[\frac{e\,({\mit\Phi}_w-{\mit\Phi}_s)}{T_e}\right]$](img1599.png)

. As is clear from the previous equation,

this is only possible provided that

. As is clear from the previous equation,

this is only possible provided that

![$\displaystyle \exp\left[\frac{e\,({\mit\Phi}_w-{\mit\Phi}_s)}{T_e}\right]\ll 1:$](img1601.png)

in a steady-state sheath, in order to prevent wall charging, and so we obtain

We conclude that, in a steady-state sheath, the wall is biased negatively with respect to the

sheath edge by an amount that is proportional to the electron temperature.

in a steady-state sheath, in order to prevent wall charging, and so we obtain

We conclude that, in a steady-state sheath, the wall is biased negatively with respect to the

sheath edge by an amount that is proportional to the electron temperature.

. Thus, hydrogen

ions enter the sheath with an initial energy

. Thus, hydrogen

ions enter the sheath with an initial energy

, fall through the sheath potential, and so impact the

wall with energy

, fall through the sheath potential, and so impact the

wall with energy

.

.

, we arrive at the following set of equations that characterize the structure of a

Langmuir sheath:

, we arrive at the following set of equations that characterize the structure of a

Langmuir sheath: