Next: Closure in Collisionless Magnetized Up: Plasma Fluid Theory Previous: MHD Equations Contents

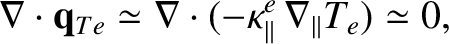

If we assume that

then the dominant term in the electron energy conservation equation

(4.202) yields

then the dominant term in the electron energy conservation equation

(4.202) yields

|

(4.206) |

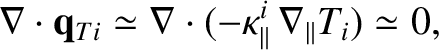

The dominant term in the ion energy conservation equation (4.205) yields

|

(4.208) |

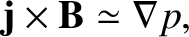

The dominant terms in the electron and ion momentum conservation equations, (4.201) and (4.204), yield

The sum of the preceding two equations gives

|

(4.212) |

. In other words, in the drift approximation, to lowest order, the plasma exists in an equilibrium state in which

the magnetic force density balances the total scalar pressure force density. It follows from the previous equation that

. In other words, in the drift approximation, to lowest order, the plasma exists in an equilibrium state in which

the magnetic force density balances the total scalar pressure force density. It follows from the previous equation that

|

(4.213) |

, and making use of Equations (4.207) and (4.209), we deduce that

, and making use of Equations (4.207) and (4.209), we deduce that

|

(4.214) |

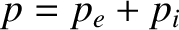

and

and

, are also constant along magnetic

field-lines. Hence, Equation (4.210) yields

, are also constant along magnetic

field-lines. Hence, Equation (4.210) yields

|

(4.215) |

Equations (4.210)–(4.211) can be inverted to give

Here, is the

is the

velocity, whereas

velocity, whereas

|

(4.218) |

|

(4.219) |

According to Equations (4.216)–(4.217), in the drift approximation, the velocity of the electron

fluid perpendicular to the magnetic field is the sum of the

velocity and the electron diamagnetic velocity. A similar statement can be made for the ion fluid.

By contrast, in the MHD approximation the perpendicular velocities of the

two fluids consist of the

velocity and the electron diamagnetic velocity. A similar statement can be made for the ion fluid.

By contrast, in the MHD approximation the perpendicular velocities of the

two fluids consist of the

velocity alone, and are,

therefore, identical to lowest order. The main difference between the

two orderings lies in the assumed magnitude of the electric field. In the

MHD limit

velocity alone, and are,

therefore, identical to lowest order. The main difference between the

two orderings lies in the assumed magnitude of the electric field. In the

MHD limit

|

(4.220) |

|

(4.221) |

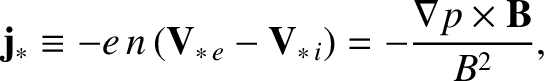

The diamagnetic velocities are so named because the diamagnetic current,

|

(4.222) |

The electron diamagnetic velocity can be written

In order to account for this velocity, let us consider a simplified case in which the electron temperature is uniform, there is a uniform density gradient running along the -direction, and the magnetic

field is parallel to the

-direction, and the magnetic

field is parallel to the  -axis. (See Figure 4.3.)

The electrons gyrate in the

-axis. (See Figure 4.3.)

The electrons gyrate in the  -

- plane in circles of radius

plane in circles of radius

. At a given point, coordinate

. At a given point, coordinate  , say, on the

, say, on the  -axis,

the electrons that come from the right and the left have traversed distances

of approximate magnitude

-axis,

the electrons that come from the right and the left have traversed distances

of approximate magnitude  . Thus, the electrons from the right originate from

regions where the particle density is approximately

. Thus, the electrons from the right originate from

regions where the particle density is approximately

greater than the regions from which the electrons from the left originate.

It follows that the

greater than the regions from which the electrons from the left originate.

It follows that the  -directed particle flux

is unbalanced, with slightly more particles moving in the

-directed particle flux

is unbalanced, with slightly more particles moving in the  -direction

than in the

-direction

than in the  -direction. Thus, there is a net particle flux

in the

-direction. Thus, there is a net particle flux

in the  -direction: that is, in the direction of

-direction: that is, in the direction of

.

The magnitude of this flux is

.

The magnitude of this flux is

|

(4.224) |

-direction, because the

-direction, because the

-directed fluxes are associated with electrons that originate from regions

where

-directed fluxes are associated with electrons that originate from regions

where  . We have now accounted for the first term on the

right-hand side of Equation (4.223).

We can account for the second term using similar arguments.

The ion diamagnetic velocity is similar in magnitude to the electron

diamagnetic velocity, but is oppositely directed, because ions gyrate

in the opposite direction to electrons.

. We have now accounted for the first term on the

right-hand side of Equation (4.223).

We can account for the second term using similar arguments.

The ion diamagnetic velocity is similar in magnitude to the electron

diamagnetic velocity, but is oppositely directed, because ions gyrate

in the opposite direction to electrons.

The most curious aspect of diamagnetic flows is that they represent fluid flows for which there is no corresponding motion of the particle guiding centers. Nevertheless, the diamagnetic velocities are real fluid velocities, and the associated diamagnetic current is a real current. For instance, the diamagnetic current contributes to force balance inside the plasma, and also gives rise to ohmic heating.