Next: Parker Model of Solar Up: Magnetohydrodynamic Fluids Previous: MHD Waves Contents

m)

from the center of the Sun (Suess 1990).

The Voyager 1 spacecraft is inferred to have crossed the heliopause in August of 2012 (Webber and McDonald 2013).

m)

from the center of the Sun (Suess 1990).

The Voyager 1 spacecraft is inferred to have crossed the heliopause in August of 2012 (Webber and McDonald 2013).

In the vicinity of the Earth, (i.e., at about 1 AU from the

Sun), the solar wind velocity typically

ranges between 300 and 1400

(Priest 1984). The average value

is approximately

(Priest 1984). The average value

is approximately

, which corresponds to about a

4 day time-of-flight from the Sun. Note that the solar wind is

both super-sonic and super-Alfvénic, and is predominately composed of protons and electrons.

, which corresponds to about a

4 day time-of-flight from the Sun. Note that the solar wind is

both super-sonic and super-Alfvénic, and is predominately composed of protons and electrons.

The solar wind was predicted theoretically by Eugine Parker (Parker 1958) a number of years before its existence was confirmed by means of satellite data (Neugebauer and Snyder 1966). Parker's prediction of a super-sonic outflow of gas from the Sun is a fascinating application of plasma physics.

The solar wind originates from the solar corona, which

is a hot, tenuous plasma, surrounding the Sun, with characteristic temperatures and

particle densities of about  K and

K and

,

respectively (Priest 1984). The corona is actually far hotter than the solar

atmosphere, or photosphere. In fact, the

temperature of the photosphere is only about

,

respectively (Priest 1984). The corona is actually far hotter than the solar

atmosphere, or photosphere. In fact, the

temperature of the photosphere is only about  K. It is

thought that the corona is heated by Alfvén waves emanating from the

photosphere (Priest 1984). The solar corona is most easily observed during a total

solar eclipse, when it is visible as a white filamentary region

immediately surrounding the Sun.

K. It is

thought that the corona is heated by Alfvén waves emanating from the

photosphere (Priest 1984). The solar corona is most easily observed during a total

solar eclipse, when it is visible as a white filamentary region

immediately surrounding the Sun.

Let us start, following Chapman (Chapman 1957), by attempting to construct a model for a static solar corona. The equation of hydrostatic equilibrium for the corona takes the form

where is the gravitational constant,

is the gravitational constant,

the solar mass (Yoder 1995), and

the solar mass (Yoder 1995), and  the radial distance from the center of the Sun.

The plasma density is written

where

the radial distance from the center of the Sun.

The plasma density is written

where  is the number

density of protons. If both protons and electrons are assumed

to possess a common temperature,

is the number

density of protons. If both protons and electrons are assumed

to possess a common temperature,  , then the coronal pressure is

given by

, then the coronal pressure is

given by

The thermal conductivity of the corona is dominated by the electron thermal conductivity, and takes the form [see Equations (4.70) and (4.89)]

|

(8.54) |

is a relatively weak function of density and

temperature. For typical coronal conditions, this conductivity is

extremely high. In fact, it is about twenty times the thermal

conductivity of copper at room temperature. The coronal heat flux density

is written

is a relatively weak function of density and

temperature. For typical coronal conditions, this conductivity is

extremely high. In fact, it is about twenty times the thermal

conductivity of copper at room temperature. The coronal heat flux density

is written

|

(8.55) |

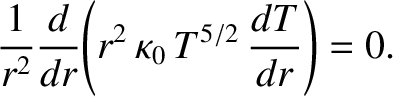

|

(8.56) |

|

(8.57) |

is conveniently taken to be the

base of the corona, where

is conveniently taken to be the

base of the corona, where

,

,

, and

, and

K (Priest 1984).

K (Priest 1984).

Equations (8.51), (8.52), (8.53), and (8.58) can be combined and integrated to give

![$\displaystyle p(r) = p(a) \exp\left\{\frac{7}{5}\,\frac{G\,M_\odot\,m_p}{2\,T(a)\,a}

\left[\left(\frac{a}{r}\right)^{5/7}-1\right]\right\}.$](img2770.png) |

(8.59) |

, the coronal pressure tends towards a finite

constant value:

, the coronal pressure tends towards a finite

constant value:

![$\displaystyle p(\infty) = p(a)\,\exp\left[-\frac{7}{5}\,\frac{G\,M_\odot\,m_p}{2\,T(a)\,a}

\right] = p(a)\,\exp\left[-\frac{14}{5}\,\frac{T_0}{T(a)}\right],$](img2772.png) |

(8.60) |

is defined in Equation (8.66).

There is, of course, nothing at large distances from the Sun that could

contain such a pressure (the pressure of the interstellar medium is

negligibly small). Thus, we conclude, following Parker, that the

static coronal model is unphysical.

is defined in Equation (8.66).

There is, of course, nothing at large distances from the Sun that could

contain such a pressure (the pressure of the interstellar medium is

negligibly small). Thus, we conclude, following Parker, that the

static coronal model is unphysical.

We have just demonstrated that a static model of the solar corona is unsatisfactory. Let us, instead, attempt to construct a dynamic model in which material flows outward from the Sun.