| (4.33) |

| (4.33) |

| (4.34) |

The ![]() th moment of the kinetic equation is obtained

by multiplying the previous equation by

th moment of the kinetic equation is obtained

by multiplying the previous equation by ![]() powers of

powers of ![]() , and integrating

over velocity space. The flow term is simplified by pulling the

divergence outside the velocity integral. The acceleration term is treated by partial

integration. These two terms couple the

, and integrating

over velocity space. The flow term is simplified by pulling the

divergence outside the velocity integral. The acceleration term is treated by partial

integration. These two terms couple the ![]() th moment

to the

th moment

to the ![]() th and

th and ![]() th moments, respectively.

th moments, respectively.

Making use of the collisional conservation laws, the zeroth moment of Equation (4.35)

yields the continuity equation for species ![]() :

:

The interpretation of Equations (4.36)-(4.38) as conservation laws is

straightforward. Suppose that ![]() is some physical quantity (for instance, the

total number of particles, the total energy, and so on), and

is some physical quantity (for instance, the

total number of particles, the total energy, and so on), and

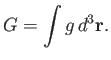

![]() is its density:

is its density:

|

(4.39) |

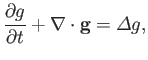

|

(4.40) |

Applying this reasoning to Equation (4.36), we see that

![]() is indeed the

species-

is indeed the

species-![]() particle flux density, and that there are no local sources or sinks of

species-

particle flux density, and that there are no local sources or sinks of

species-![]() particles.4.1 From Equation (4.37), it is apparent that the stress tensor,

particles.4.1 From Equation (4.37), it is apparent that the stress tensor, ![]() , is the species-

, is the species-![]() momentum flux density, and that

the species-

momentum flux density, and that

the species-![]() momentum is changed locally by the Lorentz force, and by collisional

friction with other species. Finally, from Equation (4.38), we see that

momentum is changed locally by the Lorentz force, and by collisional

friction with other species. Finally, from Equation (4.38), we see that

![]() is indeed the species-

is indeed the species-![]() energy flux density, and that the

species-

energy flux density, and that the

species-![]() energy is changed locally by electrical work, energy exchange with

other species, and frictional heating.

energy is changed locally by electrical work, energy exchange with

other species, and frictional heating.