Next: Exercises

Up: Collisions

Previous: Rosenbluth Potentials

Collision Times

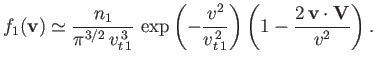

Consider collisions between particles of type  (with number density

(with number density  and mass

and mass  ), possessing the Maxwellian distribution function

), possessing the Maxwellian distribution function

![$\displaystyle f_1({\bf v})=n_1\left(\frac{m_1}{2\pi\,T}\right)^{3/2}\exp\left[-\frac{m_1\,({\bf v}-{\bf V})^2}{2\,T}\right],$](img939.png) |

(3.167) |

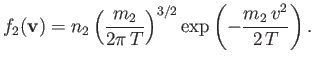

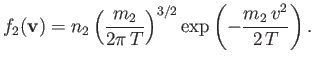

and particles of type  (with number density

(with number density  and mass

and mass  ), possessing the Maxwellian distribution function

), possessing the Maxwellian distribution function

|

(3.168) |

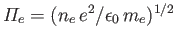

Here,  is the common temperature of the two species, and

is the common temperature of the two species, and  is the mean drift velocity of species

is the mean drift velocity of species  relative to species

relative to species  .

As we saw in the previous section, collisions with particles of type

.

As we saw in the previous section, collisions with particles of type  give rise to a velocity-dependent force acting on individual particles of

type

give rise to a velocity-dependent force acting on individual particles of

type  . This force takes the form [see Equation (3.165)]

. This force takes the form [see Equation (3.165)]

![$\displaystyle {\bf R}_{12} =- \frac{\gamma_{12}\,n_2}{m_2}\left[-\frac{F_2(\zet...

...3}\,{\bf V} + \frac{3\,F_3(\zeta)}{v^5}\,({\bf v}\cdot{\bf V})\,{\bf v}\right],$](img941.png) |

(3.169) |

where

and

and

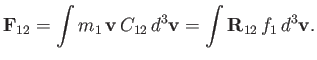

. The net force per unit volume acting on type

. The net force per unit volume acting on type  particles due to

collisions with type

particles due to

collisions with type  particles is thus

particles is thus

|

(3.170) |

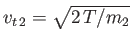

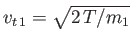

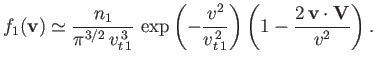

Suppose that the drift velocity,  , is much smaller than the thermal velocity,

, is much smaller than the thermal velocity,

, of type

, of type  particles.

In this case, we can write

particles.

In this case, we can write

|

(3.171) |

Hence, Equations (3.169) and (3.170) yield

|

![$\displaystyle = -\frac{\gamma_{12}\,n_1\,n_2}{\pi^{3/2}\,m_2\,v_{t\,1}^{\,3}}\i...

...(\zeta)}{v^3}\,V_i + \frac{3\,F_3(\zeta)}{v^5}\,v_k\,V_k\,v_i\right]d^3{\bf v}.$](img947.png) |

|

| |

|

(3.172) |

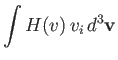

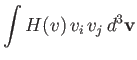

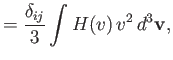

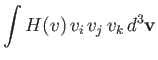

However, it follows from symmetry that

where  is a general function. Hence, Equation (3.172) reduces to

is a general function. Hence, Equation (3.172) reduces to

![$\displaystyle {\bf F}_{12} = -\frac{\gamma_{12}\,n_1\,n_2\,{\bf V}}{\pi^{3/2}\,...

...v_{t\,1}^{\,2}}\right)\left[\frac{F_3(\zeta)-F_2(\zeta)}{v^3}\right]d^3{\bf v}.$](img953.png) |

(3.176) |

It follows from Equations (3.151) and (3.152) that

|

(3.177) |

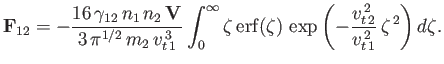

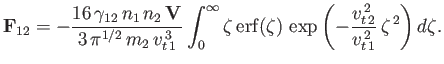

Integration by parts gives

![$\displaystyle {\bf F}_{12} = -\frac{16\,\gamma_{12}\,n_1\,n_2\,{\bf V}}{3\,\pi\...

...-\left(1+\frac{v_{t\,2}^{\,2}}{v_{t\,1}^{\,2}}\right) \zeta^{\,2}\right]d\zeta,$](img955.png) |

(3.178) |

which reduces to

![$\displaystyle {\bf F}_{12} = -\left[\frac{8\,\gamma_{12}\,n_1\,n_2}{3\,\pi^{1/2}\,m_2\,v_{t\,2}^{\,2}\,(v_{t\,1}^{\,2}+v_{t\,2}^{\,2})^{1/2}}\right]{\bf V}.$](img956.png) |

(3.179) |

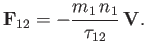

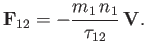

The collision time,  , associated with collisions of particles of type

, associated with collisions of particles of type  with particles of type

with particles of type  , is conventionally

defined via the following equation,

, is conventionally

defined via the following equation,

|

(3.180) |

According to this definition, the collision time is the time required for collisions with particles of type  to decelerate particles of

type

to decelerate particles of

type  to such an extent that the mean drift velocity of the latter particles with respect to the former is eliminated. At the individual

particle level, the collision time is the mean time required for the direction of motion of an individual type

to such an extent that the mean drift velocity of the latter particles with respect to the former is eliminated. At the individual

particle level, the collision time is the mean time required for the direction of motion of an individual type  particle to deviate through

approximately

particle to deviate through

approximately  as a consequence of collisions with particles of type

as a consequence of collisions with particles of type  .

According to Equations (3.112) and (3.179),

we can write

.

According to Equations (3.112) and (3.179),

we can write

|

(3.181) |

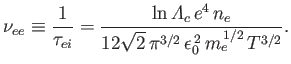

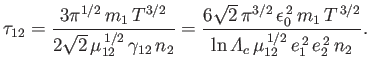

Consider a quasi-neutral plasma consisting of electrons of mass  , charge

, charge  , and number density

, and number density  , and ions

of mass

, and ions

of mass  , charge

, charge  , and number density

, and number density  . Let the two species both have Maxwellian distributions characterized by a

common temperature

. Let the two species both have Maxwellian distributions characterized by a

common temperature  , and a small relative drift velocity. It follows, from the previous analysis, that we can

identify four different collision times. First, the electron-electron collision time,

, and a small relative drift velocity. It follows, from the previous analysis, that we can

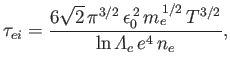

identify four different collision times. First, the electron-electron collision time,

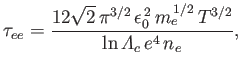

|

(3.182) |

which is the mean time required for the direction of motion of an individual electron to deviate through

approximately  as a consequence of collisions with other electrons.

Second, the electron-ion collision time,

as a consequence of collisions with other electrons.

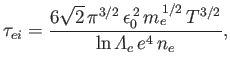

Second, the electron-ion collision time,

|

(3.183) |

which is the mean time required for the direction of motion of an individual electron to deviate through

approximately  as a consequence of collisions with ions.

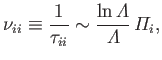

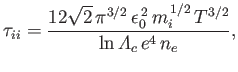

Third, the ion-ion collision time,

as a consequence of collisions with ions.

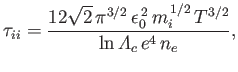

Third, the ion-ion collision time,

|

(3.184) |

which is the mean time required for the direction of motion of an individual ion to deviate through

approximately  as a consequence of collisions with other ions.

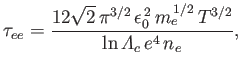

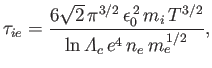

Finally, the ion-electron collision time,

as a consequence of collisions with other ions.

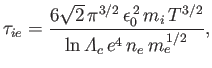

Finally, the ion-electron collision time,

|

(3.185) |

which is the mean time required for the direction of motion of an individual ion to deviate through

approximately  as a consequence of collisions with electrons. Note that these collision times are not all

of the same magnitude, as a consequence of the large difference between the electron and ion masses.

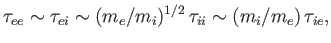

In fact,

as a consequence of collisions with electrons. Note that these collision times are not all

of the same magnitude, as a consequence of the large difference between the electron and ion masses.

In fact,

|

(3.186) |

which implies that electrons scatter electrons (through  ) at about the same rate that ions scatter electrons, but that ions scatter ions

at a significantly lower rate than ions scatter electrons, and, finally, that electrons scatter ions at a significantly lower rate than ions scatter ions.

) at about the same rate that ions scatter electrons, but that ions scatter ions

at a significantly lower rate than ions scatter electrons, and, finally, that electrons scatter ions at a significantly lower rate than ions scatter ions.

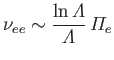

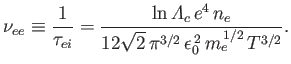

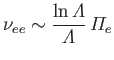

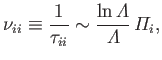

The collision frequency is simply the inverse of the collision time. Thus, the electron-electron collision frequency

is written

|

(3.187) |

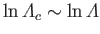

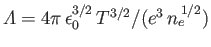

Given that

(see Section 3.10), where

(see Section 3.10), where

is the

plasma parameter (see Section 1.6),

we obtain the estimate (see Section 1.7)

is the

plasma parameter (see Section 1.6),

we obtain the estimate (see Section 1.7)

|

(3.188) |

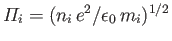

where

is the electron plasma frequency (see Section 1.4).

Likewise, the ion-ion collision frequency is such that

is the electron plasma frequency (see Section 1.4).

Likewise, the ion-ion collision frequency is such that

|

(3.189) |

where

is the ion plasma frequency.

is the ion plasma frequency.

Next: Exercises

Up: Collisions

Previous: Rosenbluth Potentials

Richard Fitzpatrick

2016-01-23

![$\displaystyle f_1({\bf v})=n_1\left(\frac{m_1}{2\pi\,T}\right)^{3/2}\exp\left[-\frac{m_1\,({\bf v}-{\bf V})^2}{2\,T}\right],$](img939.png)

![$\displaystyle f_1({\bf v})=n_1\left(\frac{m_1}{2\pi\,T}\right)^{3/2}\exp\left[-\frac{m_1\,({\bf v}-{\bf V})^2}{2\,T}\right],$](img939.png)

![]() , is much smaller than the thermal velocity,

, is much smaller than the thermal velocity,

![]() , of type

, of type ![]() particles.

In this case, we can write

particles.

In this case, we can write

![$\displaystyle {\bf F}_{12} = -\frac{\gamma_{12}\,n_1\,n_2\,{\bf V}}{\pi^{3/2}\,...

...v_{t\,1}^{\,2}}\right)\left[\frac{F_3(\zeta)-F_2(\zeta)}{v^3}\right]d^3{\bf v}.$](img953.png)

![$\displaystyle {\bf F}_{12} = -\frac{16\,\gamma_{12}\,n_1\,n_2\,{\bf V}}{3\,\pi\...

...-\left(1+\frac{v_{t\,2}^{\,2}}{v_{t\,1}^{\,2}}\right) \zeta^{\,2}\right]d\zeta,$](img955.png)

![]() , associated with collisions of particles of type

, associated with collisions of particles of type ![]() with particles of type

with particles of type ![]() , is conventionally

defined via the following equation,

, is conventionally

defined via the following equation,

![]() , charge

, charge ![]() , and number density

, and number density ![]() , and ions

of mass

, and ions

of mass ![]() , charge

, charge ![]() , and number density

, and number density ![]() . Let the two species both have Maxwellian distributions characterized by a

common temperature

. Let the two species both have Maxwellian distributions characterized by a

common temperature ![]() , and a small relative drift velocity. It follows, from the previous analysis, that we can

identify four different collision times. First, the electron-electron collision time,

, and a small relative drift velocity. It follows, from the previous analysis, that we can

identify four different collision times. First, the electron-electron collision time,