Next: Magnetic susceptibility and permeability

Up: Dielectric and magnetic media

Previous: Energy density within a

All matter is built up out of atoms, and each atom consists of

electrons in motion. The currents

associated with this motion

are termed atomic currents. Each atomic current is

a tiny closed circuit of atomic dimensions, and may therefore be

appropriately described as a magnetic dipole. If the atomic currents

of a given atom all flow in the same plane then the atomic dipole moment is directed normal

to the plane (in the sense given by the right-hand rule), and its magnitude

is the product of the total circulating current and the area of the

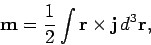

current loop. More generally, if

is the atomic current

density at the point

is the atomic current

density at the point  then the magnetic moment of the atom

is

then the magnetic moment of the atom

is

|

(856) |

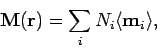

where the integral is over the volume of the atom. If there are  such

atoms or molecules per unit volume then the magnetization

such

atoms or molecules per unit volume then the magnetization  (i.e., the magnetic dipole moment per unit volume) is given

by

(i.e., the magnetic dipole moment per unit volume) is given

by

. More generally,

. More generally,

|

(857) |

where

is the average magnetic dipole moment

of the

is the average magnetic dipole moment

of the  th type of molecule in the vicinity of point

th type of molecule in the vicinity of point  ,

and

,

and  is the average number of such molecules per unit volume at

is the average number of such molecules per unit volume at

.

.

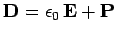

Consider a general medium which is made up of molecules which are

polarizable and possess a net magnetic moment.

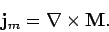

It is easily demonstrated that any circulation in the magnetization field

gives rise to an effective current density

gives rise to an effective current density

in the medium. In fact,

in the medium. In fact,

|

(858) |

This current density is called the magnetization current density,

and is usually distinguished from the true current density,

, which represents the convection of free charges in the

medium. In fact, there is a third type of current called a polarization

current, which is due to the apparent convection of bound charges.

It is easily demonstrated that the polarization current density,

, which represents the convection of free charges in the

medium. In fact, there is a third type of current called a polarization

current, which is due to the apparent convection of bound charges.

It is easily demonstrated that the polarization current density,

, is given by

, is given by

|

(859) |

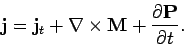

Thus, the total current density,  , in the medium takes the form

, in the medium takes the form

|

(860) |

It must be emphasized that all terms on the right-hand side of

the above equation represent

real physical currents, although only the first term is due to the motion

of real charges (over more than atomic dimensions).

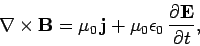

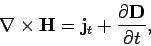

The differential form of Ampère's law is

|

(861) |

which can also be written

|

(862) |

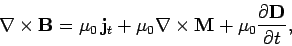

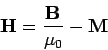

where use has been made of the definition

. The above expression can be rearranged to give

. The above expression can be rearranged to give

|

(863) |

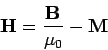

where

|

(864) |

is termed the magnetic intensity, and has the same dimensions

as  (i.e., magnetic dipole moment per unit volume).

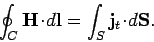

In a steady-state situation, Stokes' theorem tell us that

(i.e., magnetic dipole moment per unit volume).

In a steady-state situation, Stokes' theorem tell us that

|

(865) |

In other words, the line integral of  around some closed curve

is equal to the flux of true current through any surface attached to that

curve. Unlike the magnetic field

around some closed curve

is equal to the flux of true current through any surface attached to that

curve. Unlike the magnetic field  (which specifies

the force

(which specifies

the force

acting on a charge

acting on a charge  moving

with velocity

moving

with velocity  ),

or the magnetization

),

or the magnetization  (the magnetic dipole moment

per unit volume), the magnetic intensity

(the magnetic dipole moment

per unit volume), the magnetic intensity  has no clear physical

meaning. The only reason for introducing it is that it enables us to

calculate fields in the presence of magnetic materials without

first having to know the distribution of magnetization currents.

However, this is only possible if we possess a constitutive relation

connecting

has no clear physical

meaning. The only reason for introducing it is that it enables us to

calculate fields in the presence of magnetic materials without

first having to know the distribution of magnetization currents.

However, this is only possible if we possess a constitutive relation

connecting  and

and  .

.

Next: Magnetic susceptibility and permeability

Up: Dielectric and magnetic media

Previous: Energy density within a

Richard Fitzpatrick

2006-02-02

![]() gives rise to an effective current density

gives rise to an effective current density

![]() in the medium. In fact,

in the medium. In fact,