Next: Orbits in central force Up: Keplerian orbits Previous: Binary star systems

, then the particle's trajectory lies

on a fixed straight line that passes through the origin. [Hint: Show that

, then the particle's trajectory lies

on a fixed straight line that passes through the origin. [Hint: Show that

.]

.]

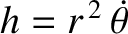

is the magnitude of the angular momentum (per unit mass)

vector

is the magnitude of the angular momentum (per unit mass)

vector

. Here,

. Here,  and

and  are plane polar coordinates.

are plane polar coordinates.

be the planet's position vector, relative to the Sun, and

let

be the planet's position vector, relative to the Sun, and

let

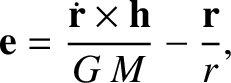

be its angular momentum per unit mass. Demonstrate that the so-called eccentricity vector,

be its angular momentum per unit mass. Demonstrate that the so-called eccentricity vector,

is the solar mass,

is the solar mass,  the orbital eccentricity, and

the orbital eccentricity, and  ,

,  are plane polar coordinates in the orbital plane (with the perihelion corresponding to

are plane polar coordinates in the orbital plane (with the perihelion corresponding to  ). Hence, show that

). Hence, show that  is a constant vector, of length

is a constant vector, of length  , that is directed from the Sun toward the

perihelion point.

, that is directed from the Sun toward the

perihelion point.

), the Earth's mean apparent radius seen from the Moon (

), the Earth's mean apparent radius seen from the Moon ( ),

and the mean number of lunar revolutions in a year (

),

and the mean number of lunar revolutions in a year ( ), show that the ratio of the Sun's mean density to that of the Earth

is

), show that the ratio of the Sun's mean density to that of the Earth

is  . (From Lamb 1923.)

. (From Lamb 1923.)

times the

mean radius of the planet. The Moon has an orbital period of 27 d. 7 h. 43 m. and a mean orbital radius that is

times the

mean radius of the planet. The Moon has an orbital period of 27 d. 7 h. 43 m. and a mean orbital radius that is  times the Earth's

mean radius. Show that the ratio of Jupiter's mean density to that of the Earth is

times the Earth's

mean radius. Show that the ratio of Jupiter's mean density to that of the Earth is  . (From Lamb 1923.)

. (From Lamb 1923.)

and a perihelion

distance of 55,000,000 miles. Find the orbital period and the comet's speed at

perihelion and aphelion.

and a perihelion

distance of 55,000,000 miles. Find the orbital period and the comet's speed at

perihelion and aphelion.

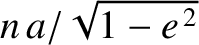

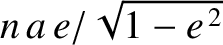

at right angles to the radius vector, and

a velocity

at right angles to the radius vector, and

a velocity

at right angles to the major axis. Here,

at right angles to the major axis. Here,  is the mean orbital angular

velocity,

is the mean orbital angular

velocity,  the major radius, and

the major radius, and  the eccentricity. (From Lamb 1923.)

the eccentricity. (From Lamb 1923.)

![$e\,h/[r_p\,(1+e)]$](img885.png) . Here,

. Here,  is the angular momentum per unit mass,

is the angular momentum per unit mass,  the orbital eccentricity, and

the orbital eccentricity, and  the

perihelion distance.

the

perihelion distance.

astronomical units from the Sun,

traveling at a speed that is

astronomical units from the Sun,

traveling at a speed that is  times the Earth's mean orbital speed. Show that the orbit of the

comet is hyperbolic, parabolic, or elliptical, depending on whether the quantity

times the Earth's mean orbital speed. Show that the orbit of the

comet is hyperbolic, parabolic, or elliptical, depending on whether the quantity

is

greater than, equal to, or less than 2, respectively. (Modified from Fowles and Cassiday 2005.)

is

greater than, equal to, or less than 2, respectively. (Modified from Fowles and Cassiday 2005.)

and

eccentricity

and

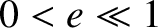

eccentricity  about the Sun. Suppose that the eccentricity of the orbit is small

(i.e.,

about the Sun. Suppose that the eccentricity of the orbit is small

(i.e.,  ), as is indeed the case for all of the planets. Demonstrate that, to first order in

), as is indeed the case for all of the planets. Demonstrate that, to first order in  , the orbit can be approximated as a circle whose center is shifted a distance

, the orbit can be approximated as a circle whose center is shifted a distance  from

the Sun, and that the planet's angular motion appears uniform when

viewed from a point (called the equant) that is shifted a distance

from

the Sun, and that the planet's angular motion appears uniform when

viewed from a point (called the equant) that is shifted a distance

from the Sun, in the same direction as the center of the circle.

[This theorem is the

basis of Ptolemy's model of planetary motion (Evans 1998).]

from the Sun, in the same direction as the center of the circle.

[This theorem is the

basis of Ptolemy's model of planetary motion (Evans 1998).]

, starting at the perihelion point? How long does it take starting at the aphelion point? The period and eccentricity of the Earth's orbit are

, starting at the perihelion point? How long does it take starting at the aphelion point? The period and eccentricity of the Earth's orbit are  days, and

days, and  , respectively.

, respectively.

is the Sun's ecliptic longitude, measured from the perigee (the point of closest approach

to the Earth), show that the Sun's apparent diameter is given by

is the Sun's ecliptic longitude, measured from the perigee (the point of closest approach

to the Earth), show that the Sun's apparent diameter is given by

and

and  are the greatest and least values of

are the greatest and least values of  . (From Lamb 1923.)

. (From Lamb 1923.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

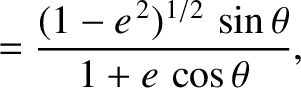

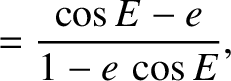

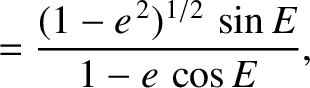

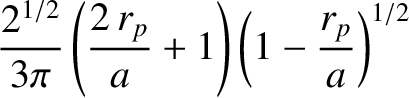

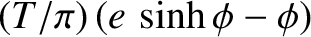

,

,  , and

, and  are the elliptic anomaly, the true anomaly, and the eccentricity, respectively.

are the elliptic anomaly, the true anomaly, and the eccentricity, respectively.

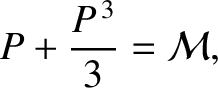

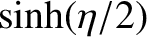

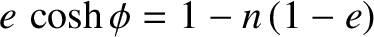

is the parabolic anomaly, and

is the parabolic anomaly, and

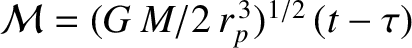

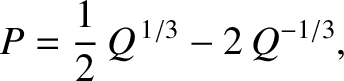

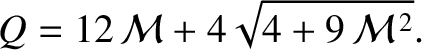

is termed the

parabolic mean anomaly. Here,

is termed the

parabolic mean anomaly. Here,  is the solar mass,

is the solar mass,  the perihelion distance, and

the perihelion distance, and  the

time of perihelion passage. Demonstrate that the preceding equation has the analytic solution

the

time of perihelion passage. Demonstrate that the preceding equation has the analytic solution

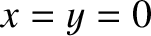

and

and  be Cartesian coordinates in the

orbital plane, such that

be Cartesian coordinates in the

orbital plane, such that  corresponds to the Sun, and the

corresponds to the Sun, and the  -axis is

parallel to the orbital major axis. Demonstrate that

-axis is

parallel to the orbital major axis. Demonstrate that

|

|

|

|

|

is the orbital major radius,

is the orbital major radius,  the eccentricity, and

the eccentricity, and  the eccentric anomaly.

the eccentric anomaly.

and

and  be Cartesian coordinates in the

orbital plane, such that

be Cartesian coordinates in the

orbital plane, such that  corresponds to the Sun, and the

corresponds to the Sun, and the  -axis is

parallel to the orbital symmetry axis. Demonstrate that

-axis is

parallel to the orbital symmetry axis. Demonstrate that

|

|

|

|

|

is the perihelion distance, and

is the perihelion distance, and  the parabolic anomaly.

the parabolic anomaly.

and

and  be Cartesian coordinates in the

orbital plane, such that

be Cartesian coordinates in the

orbital plane, such that  corresponds to the Sun, and the

corresponds to the Sun, and the  -axis is

parallel to the orbital symmetry axis. Demonstrate that

-axis is

parallel to the orbital symmetry axis. Demonstrate that

|

|

|

|

|

is the orbital major radius,

is the orbital major radius,  the eccentricity, and

the eccentricity, and  the hyperbolic anomaly.

the hyperbolic anomaly.

and

and  are the radial distances from the Sun of two neighboring points,

are the radial distances from the Sun of two neighboring points,  and

and  , on the orbit, and

if

, on the orbit, and

if  is the length of the straight line joining these two points, prove that the time,

is the length of the straight line joining these two points, prove that the time,  , required for the comet to

move from

, required for the comet to

move from  to

to  is

is

![$\displaystyle {\mit\Delta} t =\frac{T}{2\pi}\left[ (\eta -\sin\eta) -(\xi - \sin\xi)\right],

$](img915.png)

|

|

|

|

|

and

and  are the period and the major radius of the orbit, respectively.

are the period and the major radius of the orbit, respectively.

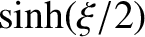

and

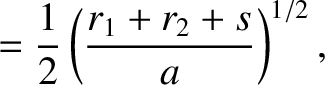

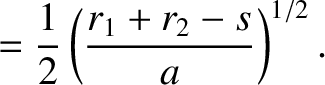

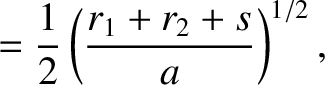

and  are the radial distances from the Sun of two neighboring points,

are the radial distances from the Sun of two neighboring points,  and

and  , on the orbit, and

if

, on the orbit, and

if  is the length of the straight line joining these two points, prove that the time required for the comet to

move from

is the length of the straight line joining these two points, prove that the time required for the comet to

move from  to

to  is

is

![$\displaystyle {\mit\Delta} t = \frac{T}{12\pi}\left[\left(\frac{r_1+r_2+s}{a}\right)^{3/2}-\left(\frac{r_1+r_2-s}{a}\right)^{3/2}\right],

$](img920.png)

and

and  are the period and the major radius of the Earth's orbit, respectively.

are the period and the major radius of the Earth's orbit, respectively.

and

and  are the radial distances from the Sun of two neighboring points,

are the radial distances from the Sun of two neighboring points,  and

and  , on the orbit, and

if

, on the orbit, and

if  is the length of the straight line joining these two points, prove that the time,

is the length of the straight line joining these two points, prove that the time,  , required for the comet to

move from

, required for the comet to

move from  to

to  is

is

![$\displaystyle {\mit\Delta} t =\frac{T}{2\pi}\left[ (\sinh\eta-\eta) -(\sinh\xi-\xi)\right],

$](img921.png)

|

|

|

|

|

is major radius of the orbit, and

is major radius of the orbit, and  is the period of an elliptical orbit with the same major radius. (From Smart 1951.)

is the period of an elliptical orbit with the same major radius. (From Smart 1951.)

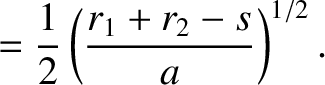

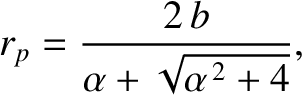

, show that the points

at which the comet intersects the Earth's orbit are given by

, show that the points

at which the comet intersects the Earth's orbit are given by

is the perihelion distance of the comet, defined at

is the perihelion distance of the comet, defined at  .

Demonstrate that the time interval that the comet remains inside the Earth's orbit is the

faction

.

Demonstrate that the time interval that the comet remains inside the Earth's orbit is the

faction

year, or

about 11 weeks.

year, or

about 11 weeks.

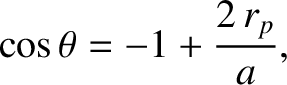

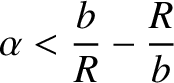

, lying in the ecliptic plane, whose

least distance from the Sun is

, lying in the ecliptic plane, whose

least distance from the Sun is  times the radius of the Earth's orbit (which is approximated as a circle).

Prove that the time that the comet remains within the Earth's orbit is

times the radius of the Earth's orbit (which is approximated as a circle).

Prove that the time that the comet remains within the Earth's orbit is

, where

, where

, and

, and  is the periodic time of a planet describing an elliptic

orbit whose major radius is equal to that of the hyperbolic orbit. (From Smart 1951.)

is the periodic time of a planet describing an elliptic

orbit whose major radius is equal to that of the hyperbolic orbit. (From Smart 1951.)

is defined as the the distance of closest approach

in the absence of any gravitational attraction between the comet and the Sun.

Demonstrate that

is defined as the the distance of closest approach

in the absence of any gravitational attraction between the comet and the Sun.

Demonstrate that

, where

, where

is the comet's angular momentum per unit mass, and

is the comet's angular momentum per unit mass, and  its energy per unit mass. Show that the relationship between the impact parameter,

its energy per unit mass. Show that the relationship between the impact parameter,  , and the

true distance of closest approach,

, and the

true distance of closest approach,  , is

, is

, and

, and  is the solar mass. Hence, deduce that if the comet is

to avoid hitting the Sun then

is the solar mass. Hence, deduce that if the comet is

to avoid hitting the Sun then

), where

), where  is the solar radius.

is the solar radius.

miles, and that the total mass of the system is

miles, and that the total mass of the system is

that of the Sun. The mean distance of the Earth from the Sun is

that of the Sun. The mean distance of the Earth from the Sun is  million miles. (From Lamb 1923.)

million miles. (From Lamb 1923.)

|

|

|

|

|

and

and

, are integrals of the the reduced equation of motion, (4.110) (in other words,

, are integrals of the the reduced equation of motion, (4.110) (in other words,  and

and  are constants of the motion). Demonstrate that, in the center of mass frame, the net angular momentum and energy of the

system are

are constants of the motion). Demonstrate that, in the center of mass frame, the net angular momentum and energy of the

system are

|

|

|

|

|

is the reduced mass.

is the reduced mass.