Next: Parabolic orbits Up: Keplerian orbits Previous: Orbital elements

(when

(when

is expressed in radians). In this case, making use of the small angle approximations

is expressed in radians). In this case, making use of the small angle approximations

and

and

, as

well as some trigonometric identities (see Section A.3),

Equations (4.72)–(4.74) simplify to give

, as

well as some trigonometric identities (see Section A.3),

Equations (4.72)–(4.74) simplify to give

|

|

(4.81) |

|

|

(4.82) |

|

|

(4.83) |

According to Table 4.1, the planets also have low-eccentricity orbits, characterized by  . In this situation, Equations (4.68)–(4.70)

can be usefully solved via series expansion in

. In this situation, Equations (4.68)–(4.70)

can be usefully solved via series expansion in  to give

to give

The preceding expressions can be combined with Equations (4.67), (4.77), (4.84), and (4.85) to produce

|

|

(4.88) |

|

|

(4.89) |

|

|

(4.90) |

|

|

(4.91) |

|

|

(4.92) |

is expressed in radians per year, and

is expressed in radians per year, and  in astronomical units.

These equations, which are valid up to first order in small quantities (i.e.,

in astronomical units.

These equations, which are valid up to first order in small quantities (i.e.,  and

and  ), illustrate

how a planet's six orbital elements—

), illustrate

how a planet's six orbital elements— ,

,

,

,  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and

—can

be used to determine its approximate position relative to the Sun as a function of time. The planet reaches its perihelion point

when the mean ecliptic longitude,

—can

be used to determine its approximate position relative to the Sun as a function of time. The planet reaches its perihelion point

when the mean ecliptic longitude,

, becomes equal to the longitude of the perihelion,

, becomes equal to the longitude of the perihelion,  . Likewise, the

planet reaches its aphelion point when

. Likewise, the

planet reaches its aphelion point when

. Furthermore, the ascending node corresponds to

. Furthermore, the ascending node corresponds to

, and the point of furthest angular distance north of the ecliptic plane (at which

, and the point of furthest angular distance north of the ecliptic plane (at which  ) corresponds

to

) corresponds

to

.

.

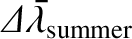

Consider the Earth's orbit about the Sun. As has already been mentioned, ecliptic longitude is measured relative to a point on the ecliptic circle—the circular path that the Sun appears to trace out against the backdrop of the stars—known as the vernal equinox. When the Sun reaches the vernal equinox, which it does every year on about March 20, day and night are equally long everywhere on the Earth (because the Sun lies in the Earth's equatorial plane). Likewise, when the Sun reaches the opposite point on the ecliptic circle, known as the autumnal equinox, which it does every year on about September 22, day and night are again equally long everywhere on the Earth. The points on the ecliptic circle half way (in an angular sense) between the equinoxes are known as the solstices. When the Sun reaches the summer solstice, which it does every year on about June 21, this marks the longest day in the Earth's northern hemisphere, and the shortest day in the southern hemisphere. Likewise, when the Sun reaches the winter solstice, which it does every year on about December 21, this marks the shortest day in the Earth's northern hemisphere and the longest day in the southern hemisphere. The period between (the Sun reaching) the vernal equinox and the summer solstice is known as spring, that between the summer solstice and the autumnal equinox as summer, that between the autumnal equinox and the winter solstice as autumn, and that between the winter solstice and the next vernal equinox as winter.

Let us calculate the approximate lengths of the seasons. It follows, from the preceding discussion, that the ecliptic

longitudes of the Sun, relative to the Earth, at the (times at which the Sun reaches the) vernal equinox, summer solstice, autumnal

equinox, and winter solstice are  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  , respectively. Hence, the

ecliptic longitudes,

, respectively. Hence, the

ecliptic longitudes,  , of the Earth, relative to the Sun, at the same times are

, of the Earth, relative to the Sun, at the same times are  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and

, respectively. Now, the mean longitude,

, respectively. Now, the mean longitude,

, of the Earth increases uniformly in time at

the rate of

, of the Earth increases uniformly in time at

the rate of  per year. Thus, the length of a given season is simply the fraction

per year. Thus, the length of a given season is simply the fraction

of a year, where

of a year, where

is the change in mean longitude associated with the season. Equation (4.91)

can be inverted to give

is the change in mean longitude associated with the season. Equation (4.91)

can be inverted to give

|

(4.93) |

.

Hence, the mean longitudes associated with the autumnal equinox, winter solstice, vernal equinox, and summer solstice, are

.

Hence, the mean longitudes associated with the autumnal equinox, winter solstice, vernal equinox, and summer solstice, are

|

|

(4.94) |

|

|

(4.95) |

|

|

(4.96) |

|

|

(4.97) |

and

and

for the Earth.)

Thus,

for the Earth.)

Thus,

|

|

(4.98) |

|

|

(4.99) |

|

|

(4.100) |

|

|

(4.101) |

days (Yoder 1995),

we deduce that spring, summer, autumn, and winter last

days (Yoder 1995),

we deduce that spring, summer, autumn, and winter last  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  days, respectively.

(In an ordinary year, the canonical dates for the vernal equinox, summer solstice, autumnal equinox, and winter solstice—March 20, June 21, September 22, and December 21, respectively—imply that spring, summer, autumn, and winter last 93, 93, 90, and 89 days, respectively, which accords well with our calculation.)

Clearly, although the deviations of the Earth's orbit from a uniform circular orbit that is concentric with the Sun seem relatively small they are still large enough to cause a noticeable difference between the lengths of the various seasons.

The preceding calculation was used, in reverse, by ancient Greek astronomers, such as Hipparchus, to determine the

eccentricity, and the longitude of the perigee, of the Sun's apparent orbit about the Earth from the observed lengths of the

seasons (Evans 1998).

days, respectively.

(In an ordinary year, the canonical dates for the vernal equinox, summer solstice, autumnal equinox, and winter solstice—March 20, June 21, September 22, and December 21, respectively—imply that spring, summer, autumn, and winter last 93, 93, 90, and 89 days, respectively, which accords well with our calculation.)

Clearly, although the deviations of the Earth's orbit from a uniform circular orbit that is concentric with the Sun seem relatively small they are still large enough to cause a noticeable difference between the lengths of the various seasons.

The preceding calculation was used, in reverse, by ancient Greek astronomers, such as Hipparchus, to determine the

eccentricity, and the longitude of the perigee, of the Sun's apparent orbit about the Earth from the observed lengths of the

seasons (Evans 1998).

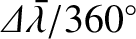

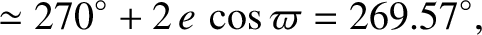

![\includegraphics[height=3.25in]{Chapter03/fig3_07.eps}](img834.png)

|