Next: Elliptic expansions Up: Useful mathematics Previous: Curvilinear coordinates

An ellipse, centered on the origin, of major radius  and minor radius

and minor radius  , that are aligned

along the

, that are aligned

along the  - and

- and  -axes, respectively (see Figure A.4), satisfies the following

well-known equation:

-axes, respectively (see Figure A.4), satisfies the following

well-known equation:

.

.

Likewise, a parabola that is aligned along the  -axis, and passes through

the origin (see Figure A.5), satisfies

-axis, and passes through

the origin (see Figure A.5), satisfies

.

.

Finally, a hyperbola that is aligned along the  -axis, and whose

asymptotes intersect at the origin (see Figure A.6), satisfies

-axis, and whose

asymptotes intersect at the origin (see Figure A.6), satisfies

.

Here,

.

Here,  is the distance of closest approach to the origin. The

asymptotes subtend an angle

is the distance of closest approach to the origin. The

asymptotes subtend an angle

with the

with the  -axis.

-axis.

It is not obvious, from the preceding formulae, what the ellipse, the parabola, and the hyperbola

have in common. It turns out, in fact, that these three curves

can all be represented as the locus of a movable point whose distance from

a fixed point is in a constant ratio to its perpendicular distance to some

fixed straight line. Let the fixed point—which is termed the focus—lie at the origin, and let

the fixed line—which is termed the directrix—correspond to  (with

(with  ). Thus, the distance of a general point (

). Thus, the distance of a general point ( ,

,  ) (which lies to the left of the directrix) from the focus is

) (which lies to the left of the directrix) from the focus is

, whereas the perpendicular distance of the point from

the directrix is

, whereas the perpendicular distance of the point from

the directrix is  . See Figure A.7.

In polar coordinates,

. See Figure A.7.

In polar coordinates,  and

and

.

Hence, the locus of a point for which

.

Hence, the locus of a point for which

and

and  are in a fixed ratio satisfies the following equation:

are in a fixed ratio satisfies the following equation:

is a constant. When expressed in terms of

polar coordinates, the preceding equation can be rearranged to give

where

is a constant. When expressed in terms of

polar coordinates, the preceding equation can be rearranged to give

where  .

.

When written in terms of Cartesian coordinates, Equation (A.104) can be rearranged to give

for . Here,

Equation (A.106) can be recognized as the equation of an ellipse

whose center lies at (

. Here,

Equation (A.106) can be recognized as the equation of an ellipse

whose center lies at ( , 0), and whose major and minor radii,

, 0), and whose major and minor radii,

and

and  , are aligned along the

, are aligned along the  - and

- and  -axes, respectively

[see Equation (A.101)]. Note, incidentally, that an ellipse

actually possesses two focii located on the major axis (

-axes, respectively

[see Equation (A.101)]. Note, incidentally, that an ellipse

actually possesses two focii located on the major axis ( ) a distance

) a distance  on either side of the

geometric center (i.e., at

on either side of the

geometric center (i.e., at  and

and

). Likewise, an ellipse possesses two directrices located

at

). Likewise, an ellipse possesses two directrices located

at

.

.

When again written in terms of Cartesian coordinates, Equation (A.104) can be rearranged to give

|

(A.110) |

. Here,

. Here,

. This is the equation of a parabola

that passes through the point (

. This is the equation of a parabola

that passes through the point ( , 0), and that is aligned

along the

, 0), and that is aligned

along the  -direction [see Equation (A.102)].

-direction [see Equation (A.102)].

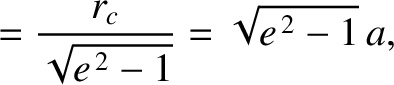

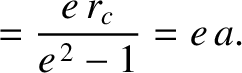

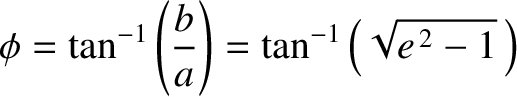

Finally, when written in terms of Cartesian coordinates, Equation (A.104) can be rearranged to give

for . Here,

. Here,

|

|

(A.112) |

|

|

(A.113) |

|

|

(A.114) |

, 0), and that

is aligned along the

, 0), and that

is aligned along the  -direction. The asymptotes subtend an angle

-direction. The asymptotes subtend an angle

|

(A.115) |

-axis [see Equation (A.103)].

-axis [see Equation (A.103)].

In conclusion, Equation (A.105) is the polar equation of a general conic

section that is confocal with the origin (i.e., the origin lies at a focus). For  , the conic section

is an ellipse. For

, the conic section

is an ellipse. For  , the conic section is a parabola. Finally, for

, the conic section is a parabola. Finally, for

, the conic section is a hyperbola.

, the conic section is a hyperbola.