Next: Spin Statistics Theorem

Up: Identical Particles

Previous: Introduction

Permutation Symmetry

Consider a quantum system consisting of two identical particles. Suppose that one of the particles--particle 1, say--is characterized by the state ket

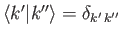

. Here,

. Here,  represents the eigenvalues of the complete set of commuting observables associated with the particle. Suppose that the other particle--particle 2--is

characterized by the state ket

represents the eigenvalues of the complete set of commuting observables associated with the particle. Suppose that the other particle--particle 2--is

characterized by the state ket

. The state ket for the whole system can be written in the product form

. The state ket for the whole system can be written in the product form

|

(9.1) |

where it is understood that the first ket corresponds to particle 1, and the second to particle 2. We can also

consider the ket

|

(9.2) |

which corresponds to a state in which particle 1 has the eigenvalues  , and particle

, and particle  the eigenvalues

the eigenvalues  .

.

Suppose that we were to measure all of the simultaneously measurable properties of our two-particle system. We might obtain the results  for one particle, and

for one particle, and  for the other.

However, we have no way of knowing whether the corresponding state ket is

for the other.

However, we have no way of knowing whether the corresponding state ket is

or

or

, or any

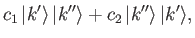

linear combination of these two kets. In other words, all state kets of the form

, or any

linear combination of these two kets. In other words, all state kets of the form

|

(9.3) |

where  and

and  are arbitrary complex numbers,

correspond to an identical set of results when the properties of the system are measured. This phenomenon is

known as exchange degeneracy. Such degeneracy is problematic because the specification of a complete set of observable eigenvalues in a system of identical particles does not seem to uniquely determine the corresponding state ket. Fortunately, nature has a way of avoiding this difficulty.

are arbitrary complex numbers,

correspond to an identical set of results when the properties of the system are measured. This phenomenon is

known as exchange degeneracy. Such degeneracy is problematic because the specification of a complete set of observable eigenvalues in a system of identical particles does not seem to uniquely determine the corresponding state ket. Fortunately, nature has a way of avoiding this difficulty.

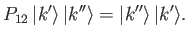

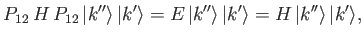

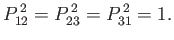

Consider the two-particle permutation operator,  , which is defined such that

, which is defined such that

|

(9.4) |

In other words,  swaps the identities of particles

swaps the identities of particles  and

and  . It is

easily appreciated that

. It is

easily appreciated that

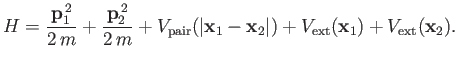

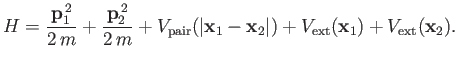

Now, the Hamiltonian of a system of two identical particles must necessarily be a symmetric function of each particle's observables (because

exchange of identical particles could not possibly affect the overall energy of the system). An example of such a Hamiltonian is

|

(9.7) |

Here, we have separated the mutual interaction of the two particles from their interaction with an external potential. [To be

more exact,

is the interaction potential, and

is the interaction potential, and

the external

potential.] It follows that if

the external

potential.] It follows that if

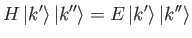

|

(9.8) |

then

|

(9.9) |

where  is the total energy.

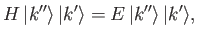

Operating on both sides of Equation (9.8) with

is the total energy.

Operating on both sides of Equation (9.8) with  , and employing Equation (9.6), we obtain

, and employing Equation (9.6), we obtain

|

(9.10) |

or

|

(9.11) |

where use has been made of Equation (9.9).

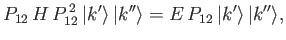

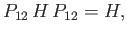

Because the

must form a complete set (otherwise, the properties of the system

would not be fully observable), we deduce that

must form a complete set (otherwise, the properties of the system

would not be fully observable), we deduce that

|

(9.12) |

which implies [from Equation (9.6)] that

![$\displaystyle [H,P_{12}] = 0.$](img3003.png) |

(9.13) |

In other words, an eigenstate of the Hamiltonian is a simultaneous eigenstate of the two-particle permutation operator,  . (See Section 1.13.)

. (See Section 1.13.)

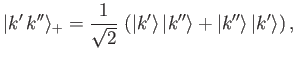

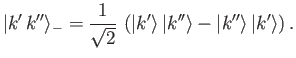

Now, according to Equation (9.6), the two-particle permutation operator possesses the eigenvalues  and

and  , respectively.

(See Exercise 1.) The corresponding properly normalized (provided that

, respectively.

(See Exercise 1.) The corresponding properly normalized (provided that

) eigenkets are

) eigenkets are

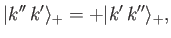

|

(9.14) |

and

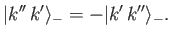

|

(9.15) |

(See Exercise 2.)

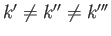

Here, it is assumed that

. Note that

. Note that

is symmetric with respect to interchange of particles--that is,

is symmetric with respect to interchange of particles--that is,

|

(9.16) |

whereas

is antisymmetric--that is,

is antisymmetric--that is,

|

(9.17) |

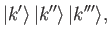

Let us, now, consider a system of three identical particles. We can represent the overall state ket as

|

(9.18) |

where  ,

,  , and

, and  are the eigenvalues of particles 1, 2, and 3, respectively. We can also

define two-particle permutation operators:

are the eigenvalues of particles 1, 2, and 3, respectively. We can also

define two-particle permutation operators:

It is easily demonstrated that

and

|

(9.25) |

As before, the Hamiltonian of the system must be a symmetric function of the particle's observables: that is,

where  is the total energy.

Using analogous arguments to those employed for the two-particle system,

we deduce that

is the total energy.

Using analogous arguments to those employed for the two-particle system,

we deduce that

![$\displaystyle [H,P_{12}] = [H,P_{23}] = [H,P_{31}] = 0.$](img3039.png) |

(9.32) |

Hence, an eigenstate of the Hamiltonian is a simultaneous eigenstate of the three two-particle permutation operators,  ,

,  , and

, and  . (See Section 1.13.)

However, according to Equation (9.25), the possible eigenvalues of these operators are

. (See Section 1.13.)

However, according to Equation (9.25), the possible eigenvalues of these operators are  . (See Exercise 1.)

. (See Exercise 1.)

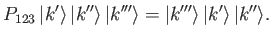

Let us define the cyclic permutation operator,  , where

, where

|

(9.33) |

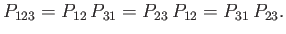

It follows that

|

(9.34) |

It is also clear from Equations (9.26) and (9.28) that

![$\displaystyle [H,P_{123}] = 0.$](img3045.png) |

(9.35) |

(See Exercise 4.)

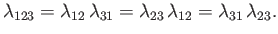

Thus, an eigenstate of the Hamiltonian is a simultaneous eigenstate of the four permutation operators  ,

,  ,

,  ,

and

,

and  . (See Section 1.13.) Let

. (See Section 1.13.) Let

,

,

,

,

and

and

represent the eigenvalues of these operators,

respectively. We know that

represent the eigenvalues of these operators,

respectively. We know that

,

,

, and

, and

. Moreover, it follows from

Equation (9.34) that

. Moreover, it follows from

Equation (9.34) that

|

(9.36) |

The previous equations imply that

|

(9.37) |

and

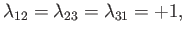

either

|

(9.38) |

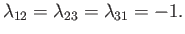

or

|

(9.39) |

In other words, the multi-particle state ket must be either totally symmetric, or totally antisymmetric, with respect to swapping the

identities of any given pair

of identical particles.

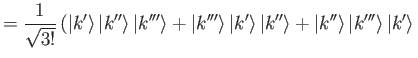

Thus, in terms of properly normalized single-particle kets, the properly normalized (provided that

) totally symmetric and totally antisymmetric kets are

) totally symmetric and totally antisymmetric kets are

and

respectively.

The previous arguments can be generalized to systems of more than three identical particles in a straightforward manner [103].

Next: Spin Statistics Theorem

Up: Identical Particles

Previous: Introduction

Richard Fitzpatrick

2016-01-22

![]() for one particle, and

for one particle, and ![]() for the other.

However, we have no way of knowing whether the corresponding state ket is

for the other.

However, we have no way of knowing whether the corresponding state ket is

![]() or

or

![]() , or any

linear combination of these two kets. In other words, all state kets of the form

, or any

linear combination of these two kets. In other words, all state kets of the form

![]() , which is defined such that

, which is defined such that

![]() and

and ![]() , respectively.

(See Exercise 1.) The corresponding properly normalized (provided that

, respectively.

(See Exercise 1.) The corresponding properly normalized (provided that

![]() ) eigenkets are

) eigenkets are

![]() , where

, where