Next: Damped Oscillatory Motion

Up: One-Dimensional Motion

Previous: Velocity Dependent Forces

Consider the motion of a point particle of mass  which is

slightly displaced from a stable equilibrium point at

which is

slightly displaced from a stable equilibrium point at  .

Suppose that the particle is moving in the conservative force-field

.

Suppose that the particle is moving in the conservative force-field  . According to the analysis of Section 3.2, in order for

. According to the analysis of Section 3.2, in order for  to be a stable equilibrium point

we require both

to be a stable equilibrium point

we require both

|

(72) |

and

|

(73) |

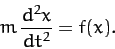

Now, our particle obeys Newton's second law of motion,

|

(74) |

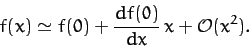

Let us assume that it always stays fairly close to its equilibrium

point. In this case, to a good approximation, we can represent  via a truncated Taylor expansion about this point. In other words,

via a truncated Taylor expansion about this point. In other words,

|

(75) |

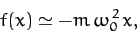

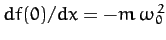

However, according to (72) and (73), the above

expression can be written

|

(76) |

where

.

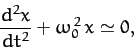

Hence, we conclude that our particle satisfies the following approximate

equation of motion,

.

Hence, we conclude that our particle satisfies the following approximate

equation of motion,

|

(77) |

provided that it does not stray too far from its equilibrium point: i.e.,

provided  does not become too large.

does not become too large.

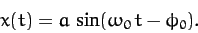

Equation (77) is called the simple harmonic equation, and

governs the motion of all one-dimensional conservative systems which are slightly

perturbed from some stable equilibrium state. The solution of Equation (77)

is well-known:

|

(78) |

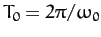

The pattern of motion described by above expression,

which is called simple harmonic motion,

is periodic in time, with repetition period

, and oscillates between

, and oscillates between  . Here,

. Here,  is called the amplitude of the motion. The parameter

is called the amplitude of the motion. The parameter  ,

known as the phase angle,

simply shifts the pattern of motion backward and forward in time.

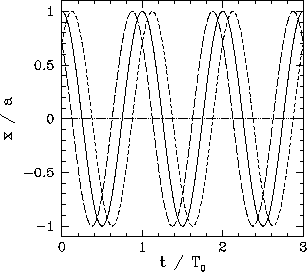

Figure 4 shows some examples of simple harmonic motion.

Here,

,

known as the phase angle,

simply shifts the pattern of motion backward and forward in time.

Figure 4 shows some examples of simple harmonic motion.

Here,  ,

,  , and

, and  correspond to the

solid, short-dashed, and long-dashed curves, respectively.

correspond to the

solid, short-dashed, and long-dashed curves, respectively.

Note that the frequency,  --and, hence, the period,

--and, hence, the period,  --of

simple harmonic motion is determined by the parameters appearing in the simple harmonic equation,

(77). However, the amplitude,

--of

simple harmonic motion is determined by the parameters appearing in the simple harmonic equation,

(77). However, the amplitude,  , and the phase angle,

, and the phase angle,  ,

are the two integration constants of this second-order ordinary differential

equation, and are, thus, determined by the initial conditions: i.e., by the particle's initial displacement and velocity.

,

are the two integration constants of this second-order ordinary differential

equation, and are, thus, determined by the initial conditions: i.e., by the particle's initial displacement and velocity.

Figure 4:

Simple harmonic motion.

|

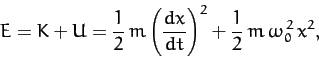

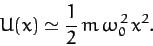

Now, from Equations (45) and (76), the potential

energy of our particle at position  is approximately

is approximately

|

(79) |

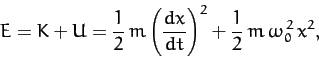

Hence, the total energy is written

|

(80) |

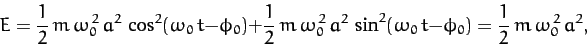

giving

|

(81) |

where use has been made of Equation (78), and the trigonometric

identity

. Note that the

total energy is constant in time, as is to be expected for a

conservative system, and is proportional to the amplitude squared

of the motion.

. Note that the

total energy is constant in time, as is to be expected for a

conservative system, and is proportional to the amplitude squared

of the motion.

Next: Damped Oscillatory Motion

Up: One-Dimensional Motion

Previous: Velocity Dependent Forces

Richard Fitzpatrick

2011-03-31

![]() --and, hence, the period,

--and, hence, the period, ![]() --of

simple harmonic motion is determined by the parameters appearing in the simple harmonic equation,

(77). However, the amplitude,

--of

simple harmonic motion is determined by the parameters appearing in the simple harmonic equation,

(77). However, the amplitude, ![]() , and the phase angle,

, and the phase angle, ![]() ,

are the two integration constants of this second-order ordinary differential

equation, and are, thus, determined by the initial conditions: i.e., by the particle's initial displacement and velocity.

,

are the two integration constants of this second-order ordinary differential

equation, and are, thus, determined by the initial conditions: i.e., by the particle's initial displacement and velocity.

![]() is approximately

is approximately