|

|

We can represent period-1 motion schematically as ![]() , where

, where ![]() represents a pattern

of motion which is repeated every period of the external drive. Likewise, we can represent

period-2 motion as

represents a pattern

of motion which is repeated every period of the external drive. Likewise, we can represent

period-2 motion as ![]() , where

, where ![]() and

and ![]() represent distinguishable patterns of motion

which are repeated every alternate period of the external drive. A period-doubling

bifurcation is represented:

represent distinguishable patterns of motion

which are repeated every alternate period of the external drive. A period-doubling

bifurcation is represented:

![]() . Clearly, all that happens

in such a bifurcation is that the pendulum suddenly decides to do something slightly different in

alternate periods of the external drive.

. Clearly, all that happens

in such a bifurcation is that the pendulum suddenly decides to do something slightly different in

alternate periods of the external drive.

|

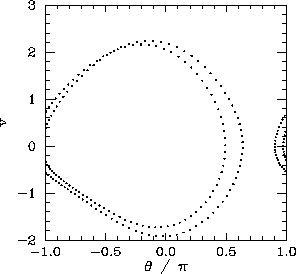

Figure 74 shows the time-asymptotic phase-space orbit of the pendulum calculated for a

value of ![]() somewhat higher than that required to trigger the above mentioned period-doubling bifurcation. It can

be seen that the orbit is left-favouring (i.e., it spends the majority of its time on

the left-hand side of the plot), and takes the form of a closed curve consisting of

two interlocked loops in phase-space.

Recall that for period-1 orbits there was only a single closed loop in phase-space.

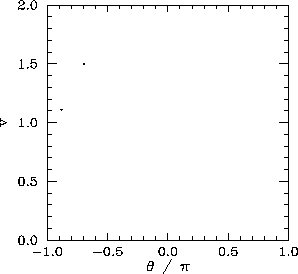

Figure 75 shows the Poincaré section of the orbit shown in Figure 74.

The fact that the section consists

of two points confirms that the orbit does indeed correspond to period-2 motion.

somewhat higher than that required to trigger the above mentioned period-doubling bifurcation. It can

be seen that the orbit is left-favouring (i.e., it spends the majority of its time on

the left-hand side of the plot), and takes the form of a closed curve consisting of

two interlocked loops in phase-space.

Recall that for period-1 orbits there was only a single closed loop in phase-space.

Figure 75 shows the Poincaré section of the orbit shown in Figure 74.

The fact that the section consists

of two points confirms that the orbit does indeed correspond to period-2 motion.

|

A period-doubling bifurcation is an example of temporal symmetry breaking. The equations of

motion of the pendulum are invariant under the transformation

![]() , where

, where

![]() is the period of the external drive. In the low amplitude (i.e., linear) limit,

the time-asymptotic motion of the pendulum always respects this symmetry. However, as we have just seen, in the

non-linear regime it is possible to obtain solutions which spontaneously break this symmetry.

Obviously, motion which repeats itself every two periods of the external drive is not

as temporally symmetric as motion which repeats every period of the drive.

is the period of the external drive. In the low amplitude (i.e., linear) limit,

the time-asymptotic motion of the pendulum always respects this symmetry. However, as we have just seen, in the

non-linear regime it is possible to obtain solutions which spontaneously break this symmetry.

Obviously, motion which repeats itself every two periods of the external drive is not

as temporally symmetric as motion which repeats every period of the drive.

|

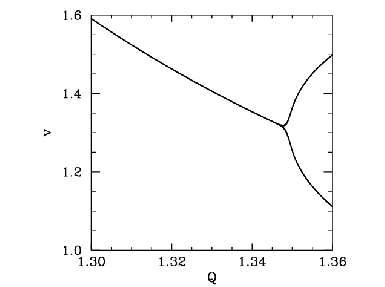

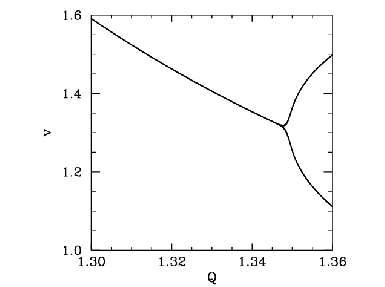

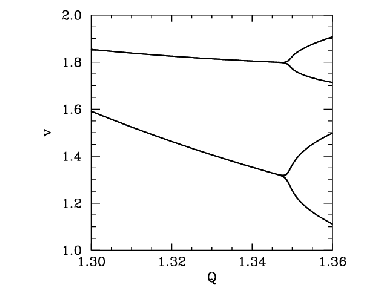

Figure 76 is essentially a continuation of Fig 68. Data is shown for two

sets of initial conditions which lead to motions converging on left-favouring (lower branch) and

right-favouring (upper branch) periodic attractors. We have already seen that the left-favouring

periodic attractor undergoes a period-doubling bifurcation at ![]() . It is clear from Figure 76

that the right-favouring attractor undergoes a similar bifurcation at almost exactly the

same

. It is clear from Figure 76

that the right-favouring attractor undergoes a similar bifurcation at almost exactly the

same ![]() -value. This is hardly surprising since, as has already

been mentioned, for fixed physical parameters (i.e.,

-value. This is hardly surprising since, as has already

been mentioned, for fixed physical parameters (i.e., ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ), the

left- and right-favouring attractors are mirror-images of one another.

), the

left- and right-favouring attractors are mirror-images of one another.