|

|

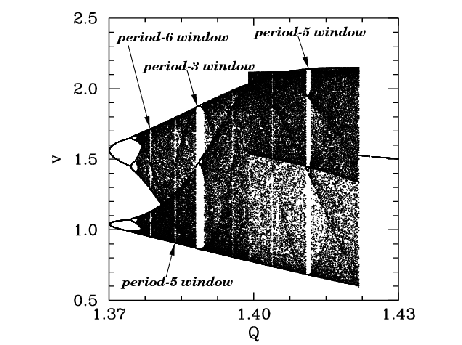

Let us return to Figure 78. Recall, that this figure shows the onset of

chaos, via a cascade of period-doubling bifurcations, as the quality-factor ![]() is gradually increased. Figure 87 is essentially a continuation of Figure 78

which shows the full extent of the chaotic region (in

is gradually increased. Figure 87 is essentially a continuation of Figure 78

which shows the full extent of the chaotic region (in ![]() -

-![]() space). It can be

seen that the chaotic region ends abruptly when

space). It can be

seen that the chaotic region ends abruptly when ![]() exceeds a critical

value, which is about

exceeds a critical

value, which is about ![]() . Beyond this critical value, the time-asymptotic motion appears to

revert to period-1 motion (i.e., the solid black region collapses to a single curve).

It can also be seen that the chaotic region contains many narrow windows in which

chaos reverts to periodic motion (i.e., the solid black region collapses

to

. Beyond this critical value, the time-asymptotic motion appears to

revert to period-1 motion (i.e., the solid black region collapses to a single curve).

It can also be seen that the chaotic region contains many narrow windows in which

chaos reverts to periodic motion (i.e., the solid black region collapses

to ![]() curves, where

curves, where ![]() is the period of the motion) for a short interval in

is the period of the motion) for a short interval in ![]() . The four widest

windows are indicated in the figure.

. The four widest

windows are indicated in the figure.

|

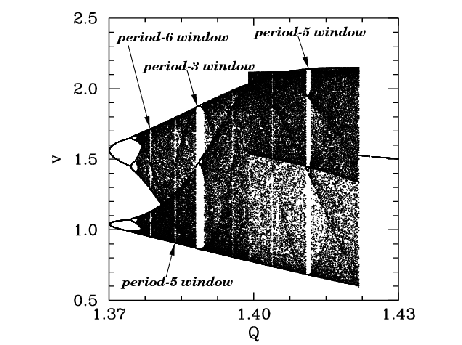

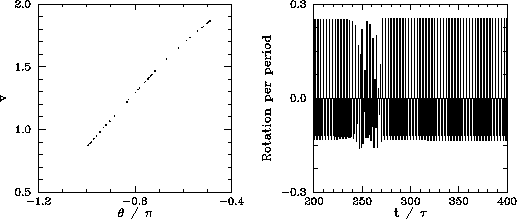

Figure 88 is a blow-up of the period-3 window shown in Figure 87. It can be

seen that the window appears ``out of the blue'' as ![]() is gradually increased. However,

it can also be seen that, as

is gradually increased. However,

it can also be seen that, as ![]() is further increased, the window breaks down,

and eventually disappears, due to the action of a cascade of period-doubling

bifurcations. The same basic mechanism operates here as in the original period-doubling

cascade, discussed in Section 15.9, except that now the orbits are of period

is further increased, the window breaks down,

and eventually disappears, due to the action of a cascade of period-doubling

bifurcations. The same basic mechanism operates here as in the original period-doubling

cascade, discussed in Section 15.9, except that now the orbits are of period ![]() , instead of

, instead of ![]() .

Note that all of the other periodic windows seen in Figure 87 break down in an analogous manner,

as

.

Note that all of the other periodic windows seen in Figure 87 break down in an analogous manner,

as ![]() is increased.

is increased.

|

|

|

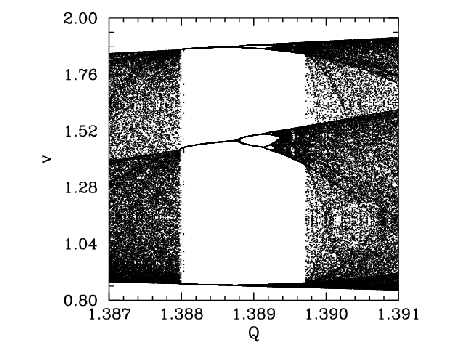

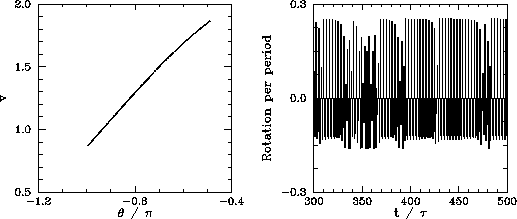

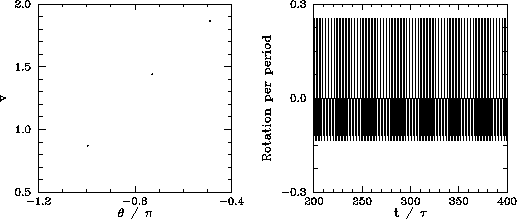

We now understand how periodic windows break down. But, how do they appear in the first place? Figures 89-91 show details of the pendulum's time-asymptotic motion calculated just before the appearance of the period-3 window (shown in Figure 88), just at the appearance of the window, and just after the appearance of the window, respectively. It can be seen, from Figure 89, that just before the appearance of the window the attractor is chaotic (i.e., its Poincaré section consists of a line, rather than a discrete set of points), and the time-asymptotic motion of the pendulum consists of intervals of period-3 motion interspersed with intervals of chaotic motion. Figure 90 shows that just at the appearance of the window the attractor loses much of its chaotic nature (i.e., its Poincaré section breaks up into a series of points), and the chaotic intervals become shorter and much less frequent. Finally, Figure 91 shows that just after the appearance of the window the attractor collapses to a period-3 attractor, and the chaotic intervals cease altogether. All of the other periodic windows seen in Figure 87 appear in an analogous manner to that just described.

According to the above discussion,

the typical time-asymptotic motion seen just prior to the appearance of a period-![]() window

consists of intervals of period-

window

consists of intervals of period-![]() motion interspersed with intervals of chaotic

motion. This type of behaviour is called intermittency, and is observed in a

wide variety of non-linear systems. As we move away from the window, in parameter

space, the intervals of periodic motion become gradually shorter and more infrequent.

Eventually, they cease altogether. Likewise, as we move towards the window, the

intervals of periodic motion become gradually longer and more frequent. Eventually,

the whole motion becomes periodic.

motion interspersed with intervals of chaotic

motion. This type of behaviour is called intermittency, and is observed in a

wide variety of non-linear systems. As we move away from the window, in parameter

space, the intervals of periodic motion become gradually shorter and more infrequent.

Eventually, they cease altogether. Likewise, as we move towards the window, the

intervals of periodic motion become gradually longer and more frequent. Eventually,

the whole motion becomes periodic.

In 1973, Metropolis and co-workers investigated a class of simple mathematical models which all

exhibit a transition to chaos, via a cascade of period-doubling bifurcations, as

some control parameter ![]() is increased.

is increased.![[*]](footnote.png) They were able to demonstrate

that, for these models, the order in which stable periodic orbits occur as

They were able to demonstrate

that, for these models, the order in which stable periodic orbits occur as ![]() is

increased is fixed.

That is, stable periodic attractors always occur in the same sequence as

is

increased is fixed.

That is, stable periodic attractors always occur in the same sequence as

![]() is varied. This sequence is

called the universal or U-sequence. It is possible to make a fairly

convincing argument that any physical system which exhibits a transition to chaos

via a sequence of period-doubling bifurcations should also exhibit the U-sequence

of stable periodic attractors.

Up to period-6, the U-sequence is

is varied. This sequence is

called the universal or U-sequence. It is possible to make a fairly

convincing argument that any physical system which exhibits a transition to chaos

via a sequence of period-doubling bifurcations should also exhibit the U-sequence

of stable periodic attractors.

Up to period-6, the U-sequence is

![[*]](footnote.png) The existence of

a universal sequence of stable periodic orbits in dynamical systems which

exhibit a transition to chaos via a cascade of period-doubling bifurcations

is another indication that

chaos is a universal phenomenon.

The existence of

a universal sequence of stable periodic orbits in dynamical systems which

exhibit a transition to chaos via a cascade of period-doubling bifurcations

is another indication that

chaos is a universal phenomenon.