|

![[*]](footnote.png) Furthermore, let us investigate any changes which

may develop in the nature of the

pendulum's time-asymptotic motion

as the quality-factor

Furthermore, let us investigate any changes which

may develop in the nature of the

pendulum's time-asymptotic motion

as the quality-factor

|

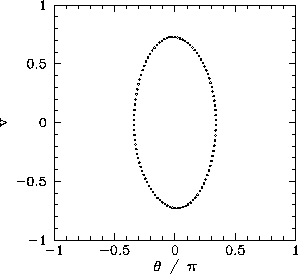

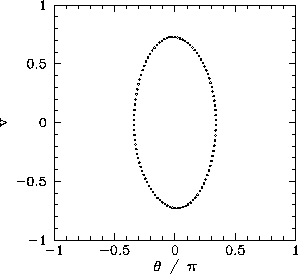

Figure 62 shows a time-asymptotic orbit in phase-space

calculated numerically for a case where ![]() is sufficiently

small (i.e.,

is sufficiently

small (i.e., ![]() ) that the small angle approximation holds reasonably well. Not surprisingly,

the orbit is very similar to the analytic orbits

described in Section 15.3. The fact that the orbit consists

of a single loop, and forms a closed curve in phase-space,

strongly suggests that the corresponding

motion is periodic with the same period as the external drive--we term this type of motion

period-1 motion. More generally, period-

) that the small angle approximation holds reasonably well. Not surprisingly,

the orbit is very similar to the analytic orbits

described in Section 15.3. The fact that the orbit consists

of a single loop, and forms a closed curve in phase-space,

strongly suggests that the corresponding

motion is periodic with the same period as the external drive--we term this type of motion

period-1 motion. More generally, period-![]() motion consists of motion which

repeats itself exactly every

motion consists of motion which

repeats itself exactly every ![]() periods of the external drive (and, obviously,

does not repeat itself on any time-scale less than

periods of the external drive (and, obviously,

does not repeat itself on any time-scale less than ![]() periods). Of course, period-1 motion

is the only allowed time-asymptotic motion in the small angle limit.

periods). Of course, period-1 motion

is the only allowed time-asymptotic motion in the small angle limit.

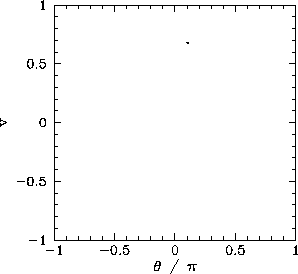

It would certainly be helpful

to possess a graphical test for period-![]() motion. In fact, such a test was developed more than a

hundred years ago by the

French mathematician Henry Poincaré. Nowadays, it is called a

Poincaré section in his honour. The idea of a Poincaré section, as applied

to a periodically driven pendulum, is very simple.

As before, we calculate the time-asymptotic motion of the pendulum, and visualize it as a

series of points in

motion. In fact, such a test was developed more than a

hundred years ago by the

French mathematician Henry Poincaré. Nowadays, it is called a

Poincaré section in his honour. The idea of a Poincaré section, as applied

to a periodically driven pendulum, is very simple.

As before, we calculate the time-asymptotic motion of the pendulum, and visualize it as a

series of points in ![]() -

-![]() phase-space. However, we only plot one point per period of the external drive. To be more

exact, we only plot a point when

phase-space. However, we only plot one point per period of the external drive. To be more

exact, we only plot a point when

| (1250) |

|

Figure 63 displays the Poincaré section of the orbit shown in Figure 62. The fact that the section consists of a single point confirms that the motion displayed in Figure 62 is indeed period-1 motion.