Next: Coordinate Transformations

Up: Vector Algebra and Vector

Previous: Vector Algebra

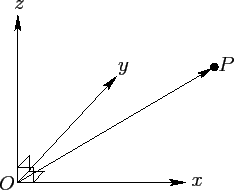

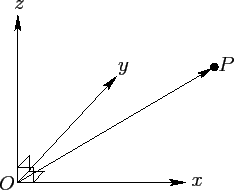

Consider a Cartesian coordinate system  consisting of

an origin,

consisting of

an origin,  , and three mutually perpendicular coordinate axes,

, and three mutually perpendicular coordinate axes,  ,

,  , and

, and

--see Figure A.99. Such a system is said to be right-handed if, when looking along the

--see Figure A.99. Such a system is said to be right-handed if, when looking along the  direction, a

direction, a  clockwise

rotation about

clockwise

rotation about  is required to take

is required to take  into

into  . Otherwise, it is said to be left-handed. In physics, it is conventional to always use right-handed coordinate systems.

. Otherwise, it is said to be left-handed. In physics, it is conventional to always use right-handed coordinate systems.

Figure A.99:

A right-handed Cartesian coordinate system.

|

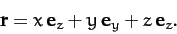

It is convenient to define unit vectors,  ,

,  , and

, and  , parallel to

, parallel to  ,

,  , and

, and  , respectively.

Incidentally, a unit vector is a vector whose magnitude is unity. The position vector,

, respectively.

Incidentally, a unit vector is a vector whose magnitude is unity. The position vector,  , of some general point

, of some general point  whose Cartesian coordinates

are (

whose Cartesian coordinates

are ( ,

,  ,

,  ) is then given by

) is then given by

|

(1271) |

In other words, we can get from  to

to  by moving a distance

by moving a distance  parallel to

parallel to  , then a distance

, then a distance

parallel to

parallel to  , and then a distance

, and then a distance  parallel to

parallel to  . Similarly, if

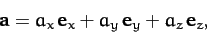

. Similarly, if  is an arbitrary vector then

is an arbitrary vector then

|

(1272) |

where  ,

,  , and

, and  are termed the Cartesian components of

are termed the Cartesian components of  . It is coventional to write

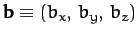

. It is coventional to write

.

It follows that

.

It follows that

,

,

, and

, and

. Of course,

. Of course,

.

.

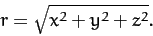

According to the three-dimensional generalization of the Pythagorean theorem, the distance

is

given by

is

given by

|

(1273) |

By analogy, the magnitude of a general vector  takes the form

takes the form

|

(1274) |

If

and

and

then it is

easily demonstrated that

then it is

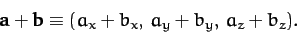

easily demonstrated that

|

(1275) |

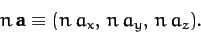

Furthermore, if  is a scalar then it is apparent that

is a scalar then it is apparent that

|

(1276) |

Next: Coordinate Transformations

Up: Vector Algebra and Vector

Previous: Vector Algebra

Richard Fitzpatrick

2011-03-31

![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() , parallel to

, parallel to ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() , respectively.

Incidentally, a unit vector is a vector whose magnitude is unity. The position vector,

, respectively.

Incidentally, a unit vector is a vector whose magnitude is unity. The position vector, ![]() , of some general point

, of some general point ![]() whose Cartesian coordinates

are (

whose Cartesian coordinates

are (![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ) is then given by

) is then given by

![]() is

given by

is

given by

![]() and

and

![]() then it is

easily demonstrated that

then it is

easily demonstrated that