Next: Spherical Interfaces

Up: Surface Tension

Previous: Introduction

Young-Laplace Equation

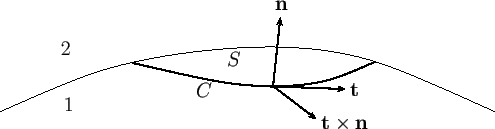

Consider an interface separating two immiscible fluids that are in equilibrium with one another. Let these two

fluids be denoted 1 and 2. Consider an arbitrary segment  of this interface that is enclosed by some closed curve

of this interface that is enclosed by some closed curve  .

Let

.

Let  denote a unit tangent to the curve, and let

denote a unit tangent to the curve, and let  denote a unit normal to the

interface directed from fluid 1 to fluid 2. (Note that

denote a unit normal to the

interface directed from fluid 1 to fluid 2. (Note that  circulates around

circulates around  in a

right-handed manner. See Figure 3.1.) Suppose that

in a

right-handed manner. See Figure 3.1.) Suppose that  and

and  are the

pressures of fluids 1 and 2, respectively, on either side of

are the

pressures of fluids 1 and 2, respectively, on either side of  . Finally, let

. Finally, let  be the (uniform)

surface tension at the interface.

be the (uniform)

surface tension at the interface.

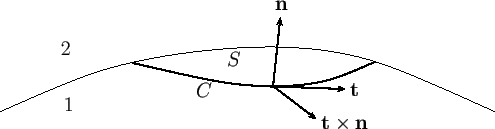

Figure 3.1:

Interface between two immiscible fluids.

|

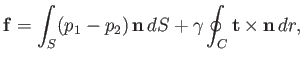

The net force acting on  is

is

|

(3.1) |

where

is an element of

is an element of  , and

, and

an element of

an element of  . Here, the first term on the

right-hand side is the net normal force due to the pressure difference across the interface, whereas the

second term is the net surface tension force.

Note that body forces play no role in Equation (3.1), because the interface has zero volume. Furthermore,

viscous forces can be neglected, because both fluids are static.

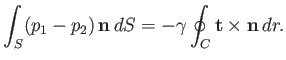

In equilibrium,

the net force acting on

. Here, the first term on the

right-hand side is the net normal force due to the pressure difference across the interface, whereas the

second term is the net surface tension force.

Note that body forces play no role in Equation (3.1), because the interface has zero volume. Furthermore,

viscous forces can be neglected, because both fluids are static.

In equilibrium,

the net force acting on  must be zero: that is,

must be zero: that is,

|

(3.2) |

(In fact, the net force would be zero even in the absence of equilibrium, because the interface has zero mass.)

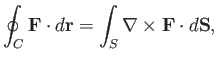

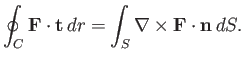

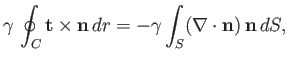

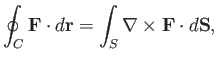

Applying the curl theorem (see Section A.22) to the curve  , we find that

, we find that

|

(3.3) |

where  is a general vector field. This theorem can also be written

is a general vector field. This theorem can also be written

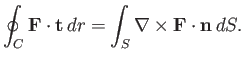

|

(3.4) |

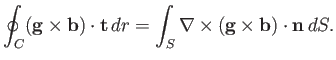

Suppose that

, where

, where  is an arbitrary constant vector. We obtain

is an arbitrary constant vector. We obtain

|

(3.5) |

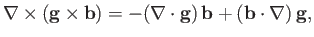

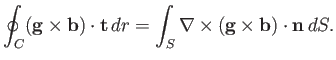

However, the vector identity (A.179) yields

|

(3.6) |

as  is a constant vector.

Hence, we get

is a constant vector.

Hence, we get

![$\displaystyle {\bf b}\cdot\oint_C {\bf t}\times {\bf g}\,dr = {\bf b}\cdot\!\int_S[(\nabla {\bf g})\cdot{\bf n} - (\nabla\cdot{\bf g})\,{\bf n}]\,dS,$](img1099.png) |

(3.7) |

where

.

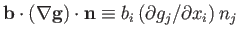

Now, because

.

Now, because  is also an arbitrary vector, the previous equation gives

is also an arbitrary vector, the previous equation gives

![$\displaystyle \oint_C {\bf t}\times {\bf g}\,dr = \int_S\left[(\nabla {\bf g})\cdot{\bf n} - (\nabla\cdot{\bf g})\,{\bf n}\right]dS.$](img1101.png) |

(3.8) |

Taking

, we find that

, we find that

![$\displaystyle \gamma\oint_C {\bf t}\times {\bf n}\,dr= \gamma\int_S \left[(\nabla {\bf n})\cdot {\bf n} - (\nabla\cdot {\bf n})\,{\bf n}\right]dS.$](img1103.png) |

(3.9) |

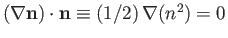

But,

, because

, because  is a unit vector. Thus, we obtain

is a unit vector. Thus, we obtain

|

(3.10) |

which can be combined with Equation (3.2) to give

![$\displaystyle \int_S\left[(p_1-p_2)-\gamma\,(\nabla\cdot{\bf n})\right]{\bf n}\,dS = 0.$](img1106.png) |

(3.11) |

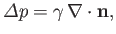

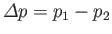

Finally, given that  is arbitrary, the previous expression reduces to the pressure balance constraint

is arbitrary, the previous expression reduces to the pressure balance constraint

|

(3.12) |

where

.

The previous relation is generally known as the Young-Laplace equation, and is named after Thomas Young (1773-1829), who developed the qualitative theory of surface tension in 1805, and Pierre-Simon Laplace (1749-1827) who completed the mathematical description in the following year.

The Young-Laplace equation

can also be derived by minimizing the free energy of the interface. (See Section 3.8.) Note that

.

The previous relation is generally known as the Young-Laplace equation, and is named after Thomas Young (1773-1829), who developed the qualitative theory of surface tension in 1805, and Pierre-Simon Laplace (1749-1827) who completed the mathematical description in the following year.

The Young-Laplace equation

can also be derived by minimizing the free energy of the interface. (See Section 3.8.) Note that

is

the jump in pressure seen when crossing the interface in the opposite direction to

is

the jump in pressure seen when crossing the interface in the opposite direction to  .

Of course, a plane interface is characterized by

.

Of course, a plane interface is characterized by

. On the other hand, a curved

interface generally has

. On the other hand, a curved

interface generally has

. In fact,

. In fact,

measures the local

mean curvature of the interface. Thus, according to the Young-Laplace equation, there is a pressure jump across

a curved interface between two immiscible fluids, the

magnitude of the jump being proportional to the surface tension.

measures the local

mean curvature of the interface. Thus, according to the Young-Laplace equation, there is a pressure jump across

a curved interface between two immiscible fluids, the

magnitude of the jump being proportional to the surface tension.

Next: Spherical Interfaces

Up: Surface Tension

Previous: Introduction

Richard Fitzpatrick

2016-03-31

![]() is

is

![]() , we find that

, we find that

![$\displaystyle {\bf b}\cdot\oint_C {\bf t}\times {\bf g}\,dr = {\bf b}\cdot\!\int_S[(\nabla {\bf g})\cdot{\bf n} - (\nabla\cdot{\bf g})\,{\bf n}]\,dS,$](img1099.png)

![$\displaystyle \oint_C {\bf t}\times {\bf g}\,dr = \int_S\left[(\nabla {\bf g})\cdot{\bf n} - (\nabla\cdot{\bf g})\,{\bf n}\right]dS.$](img1101.png)

![$\displaystyle \gamma\oint_C {\bf t}\times {\bf n}\,dr= \gamma\int_S \left[(\nabla {\bf n})\cdot {\bf n} - (\nabla\cdot {\bf n})\,{\bf n}\right]dS.$](img1103.png)

![$\displaystyle \int_S\left[(p_1-p_2)-\gamma\,(\nabla\cdot{\bf n})\right]{\bf n}\,dS = 0.$](img1106.png)