Next: Maclaurin Spheroids

Up: Hydrostatics

Previous: Rotational Hydrostatics

Consider a self-gravitating liquid body in outer space that is rotating uniformly about some fixed axis passing

through its center of mass. What is the shape of the body's bounding surface?

This famous theoretical problem had its origins in investigations of the figure of a rotating planet, such as the Earth, that were undertaken by

Newton, Maclaurin, Jacobi, Meyer, Liouville, Dirichlet, Dedekind,

Riemann, and other celebrated scientists, in the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries (Chandrasekhar 1969). Incidentally, it is reasonable to treat the Earth as a liquid,

for the purpose of this calculation, because

the shear strength of the solid rock out of which the terrestrial crust is composed is nowhere near sufficient to allow the actual shape

of the Earth to deviate

significantly from that of a hypothetical liquid Earth (Fitzpatrick 2012).

In a co-rotating reference frame, the shape

of a self-gravitating, rotating, liquid planet is determined by a competition between fluid pressure, gravity, and the fictitious centrifugal

force. The latter force opposes gravity in the plane perpendicular to the axis of rotation. Of course, in the absence

of rotation, the planet would be spherical. Thus, we would expect rotation to cause

the planet to expand in the plane perpendicular to the rotation axis, and to contract along the rotation axis

(in order to conserve volume).

For the sake of simplicity, we shall restrict our investigation to a rotating planet of uniform density whose outer

boundary is ellipsoidal. An ellipsoid is the three-dimensional generalization of an ellipse. Let us adopt the right-handed Cartesian

coordinate system  ,

,  ,

,  .

An ellipse whose principal axes are aligned along the

.

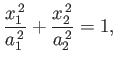

An ellipse whose principal axes are aligned along the  - and

- and  -axes satisfies

-axes satisfies

|

(2.94) |

where  and

and  are the corresponding principal radii. Moreover, as is easily demonstrated,

are the corresponding principal radii. Moreover, as is easily demonstrated,

where  is the area,

is the area,  an element of

an element of  , and the integrals are taken over the whole

interior of the ellipse.

Likewise,

an ellipsoid whose principal axes are aligned along the

, and the integrals are taken over the whole

interior of the ellipse.

Likewise,

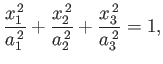

an ellipsoid whose principal axes are aligned along the  -,

-,  -, and

-, and  -axes satisfies

-axes satisfies

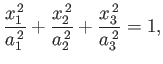

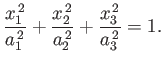

|

(2.98) |

where  ,

,  , and

, and  are the corresponding principal radii. Moreover, as is easily demonstrated,

are the corresponding principal radii. Moreover, as is easily demonstrated,

where  is the volume,

is the volume,  an element of

an element of  , and the integrals are taken over the whole

interior of the ellipsoid.

, and the integrals are taken over the whole

interior of the ellipsoid.

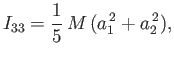

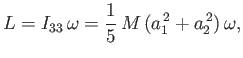

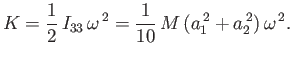

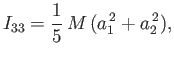

Suppose that the planet is rotating uniformly about the  -axis at the fixed angular velocity

-axis at the fixed angular velocity  . The

planet's moment of inertia about this axis is [cf., Equation (2.100)]

. The

planet's moment of inertia about this axis is [cf., Equation (2.100)]

|

(2.102) |

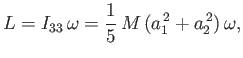

where  is its mass. Thus, the planet's angular momentum is

is its mass. Thus, the planet's angular momentum is

|

(2.103) |

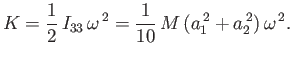

and its rotational kinetic energy becomes

|

(2.104) |

According to Equations (2.83) and (2.84), the fluid pressure distribution within the planet takes the form

![$\displaystyle p = p_0'-\rho\left[{\mit\Psi}-\frac{1}{2}\,\omega^{\,2}\,(x_1^{\,2}+x_2^{\,2})\right],$](img855.png) |

(2.105) |

where

is the gravitational potential (i.e., the gravitational potential energy of a unit test mass) due to

the planet,

is the gravitational potential (i.e., the gravitational potential energy of a unit test mass) due to

the planet,  the

uniform planetary mass density, and

the

uniform planetary mass density, and

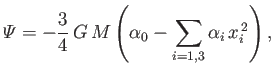

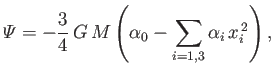

a constant. However, it is demonstrated in Appendix D that the

gravitational potential inside a homogeneous self-gravitating ellipsoidal body can be written

(Chandrasekhar 1969; Lamb 1993)

a constant. However, it is demonstrated in Appendix D that the

gravitational potential inside a homogeneous self-gravitating ellipsoidal body can be written

(Chandrasekhar 1969; Lamb 1993)

|

(2.106) |

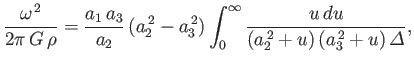

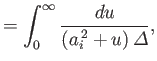

where  is the universal gravitational constant (Yoder 1995), and

is the universal gravitational constant (Yoder 1995), and

Thus, we obtain

![$\displaystyle p = p_0 - \frac{1}{2}\,\rho\left[\left(\frac{3}{2}\,G\,M\,\alpha_...

..._2-\omega^{\,2}\right)x_2^{\,2}+ \frac{3}{2}\,G\,M\,\alpha_3\,x_3^{\,2}\right],$](img863.png) |

(2.110) |

where  is the central fluid pressure. The pressure at the planet's outer boundary

must be zero, otherwise there would be a force imbalance across the boundary. In other words,

we require

is the central fluid pressure. The pressure at the planet's outer boundary

must be zero, otherwise there would be a force imbalance across the boundary. In other words,

we require

![$\displaystyle \frac{1}{2}\,\rho\left[\left(\frac{3}{2}\,G\,M\,\alpha_1-\omega^{...

...ega^{\,2}\right)x_2^{\,2}+ \frac{3}{2}\,G\,M\,\alpha_3\,x_3^{\,2}\right] = p_0,$](img864.png) |

(2.111) |

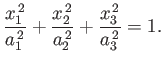

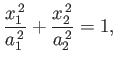

whenever

|

(2.112) |

The previous two equations can only be simultaneously satisfied if

![$\displaystyle \left[\alpha_1-\frac{\omega^{\,2}}{(3/2)\,G\,M}\right]a_1^{\,2} =...

...alpha_2-\frac{\omega^{\,2}}{(3/2)\,G\,M}\right]a_2^{\,2} = \alpha_3\,a_3^{\,2}.$](img866.png) |

(2.113) |

Rearranging the previous expression, we obtain

|

(2.114) |

subject to the constraint

![$\displaystyle (a_1^{\,2}-a_2^{\,2})\int_0^\infty\left[\frac{a_1^{\,2}\,a_2^{\,2...

...a_2^{\,2}+u)}- \frac{a_3^{\,2}}{(a_3^{\,2}+u)}\right]\frac{du}{\mit\Delta} = 0,$](img868.png) |

(2.115) |

where use has been made of Equation (2.99).

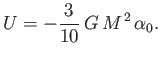

Finally, according to Appendix D, the net gravitational potential energy of the planet is

|

(2.116) |

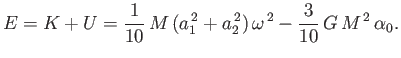

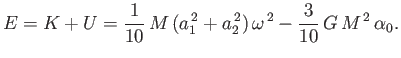

Hence, the body's total mechanical energy becomes

|

(2.117) |

Next: Maclaurin Spheroids

Up: Hydrostatics

Previous: Rotational Hydrostatics

Richard Fitzpatrick

2016-03-31

![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() .

An ellipse whose principal axes are aligned along the

.

An ellipse whose principal axes are aligned along the ![]() - and

- and ![]() -axes satisfies

-axes satisfies

![]() -axis at the fixed angular velocity

-axis at the fixed angular velocity ![]() . The

planet's moment of inertia about this axis is [cf., Equation (2.100)]

. The

planet's moment of inertia about this axis is [cf., Equation (2.100)]

![$\displaystyle p = p_0'-\rho\left[{\mit\Psi}-\frac{1}{2}\,\omega^{\,2}\,(x_1^{\,2}+x_2^{\,2})\right],$](img855.png)

![$\displaystyle p = p_0 - \frac{1}{2}\,\rho\left[\left(\frac{3}{2}\,G\,M\,\alpha_...

..._2-\omega^{\,2}\right)x_2^{\,2}+ \frac{3}{2}\,G\,M\,\alpha_3\,x_3^{\,2}\right],$](img863.png)

![$\displaystyle \frac{1}{2}\,\rho\left[\left(\frac{3}{2}\,G\,M\,\alpha_1-\omega^{...

...ega^{\,2}\right)x_2^{\,2}+ \frac{3}{2}\,G\,M\,\alpha_3\,x_3^{\,2}\right] = p_0,$](img864.png)

![$\displaystyle \left[\alpha_1-\frac{\omega^{\,2}}{(3/2)\,G\,M}\right]a_1^{\,2} =...

...alpha_2-\frac{\omega^{\,2}}{(3/2)\,G\,M}\right]a_2^{\,2} = \alpha_3\,a_3^{\,2}.$](img866.png)