Next: Laplacian Operator

Up: Vectors and Vector Fields

Previous: Grad Operator

Divergence

Let us start with a vector field

. Consider

. Consider

over some closed surface

over some closed surface  , where

, where  denotes an outward

pointing surface element. This surface integral is usually called the

flux of

denotes an outward

pointing surface element. This surface integral is usually called the

flux of  out of

out of  . If

. If  represents the velocity of some fluid

then

represents the velocity of some fluid

then

is the rate of fluid flow out of

is the rate of fluid flow out of  .

.

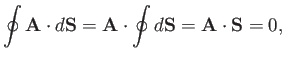

If  is constant in space then it is easily demonstrated that the net

flux out of

is constant in space then it is easily demonstrated that the net

flux out of  is zero. In fact,

is zero. In fact,

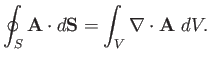

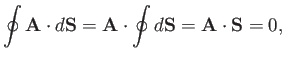

|

(A.129) |

because the vector area  of a closed surface is zero.

of a closed surface is zero.

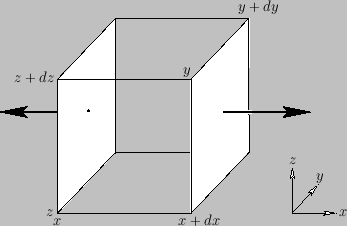

Figure A.21:

Flux of a vector field out of a small box.

|

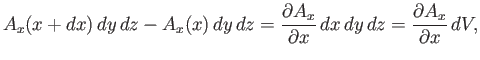

Suppose, now, that  is not uniform in space. Consider a very small

rectangular volume over which

is not uniform in space. Consider a very small

rectangular volume over which  hardly varies. The contribution to

hardly varies. The contribution to

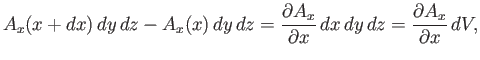

from the two faces normal to the

from the two faces normal to the  -axis is

-axis is

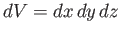

|

(A.130) |

where

is the volume element. (See Figure A.21.)

There are analogous contributions

from the sides normal to the

is the volume element. (See Figure A.21.)

There are analogous contributions

from the sides normal to the  - and

- and  -axes, so the total of all the contributions

is

-axes, so the total of all the contributions

is

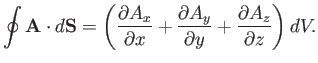

|

(A.131) |

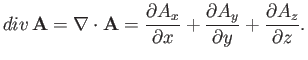

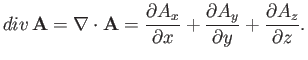

The divergence of a vector field is defined

|

(A.132) |

Divergence is a good scalar (i.e., it is coordinate

independent),

because it is the dot product of

the vector operator  with

with  . The formal definition of

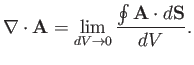

. The formal definition of

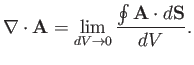

is

is

|

(A.133) |

This definition is independent of the shape of the infinitesimal volume

element.

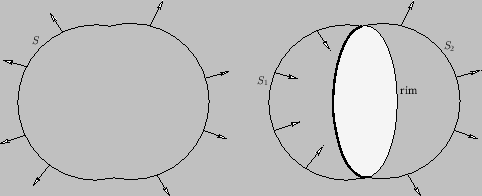

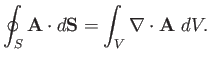

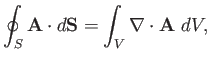

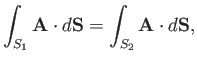

One of the most important results in vector field theory is the so-called

divergence theorem. This states that for any volume

surrounded by a closed surface

surrounded by a closed surface  ,

,

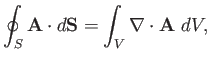

|

(A.134) |

where  is an outward pointing volume element.

The proof is very

straightforward. We divide up the volume into very many infinitesimal cubes, and

sum

is an outward pointing volume element.

The proof is very

straightforward. We divide up the volume into very many infinitesimal cubes, and

sum

over all of the surfaces. The contributions

from the interior surfaces cancel out, leaving just the contribution from the outer

surface. (See Figure A.22.) We can use Equation (A.131) for each cube individually. This tells us that

the summation is equivalent to

over all of the surfaces. The contributions

from the interior surfaces cancel out, leaving just the contribution from the outer

surface. (See Figure A.22.) We can use Equation (A.131) for each cube individually. This tells us that

the summation is equivalent to

over the whole

volume. Thus, the integral of

over the whole

volume. Thus, the integral of

over the outer surface is

equal to the integral of

over the outer surface is

equal to the integral of

over the whole volume, which

proves the divergence theorem.

over the whole volume, which

proves the divergence theorem.

Figure A.22:

The divergence theorem.

|

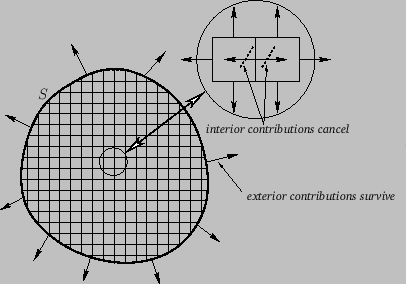

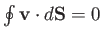

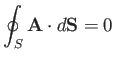

Now, for a vector field with

,

,

|

(A.135) |

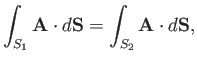

for any closed surface  . So, for two surfaces,

. So, for two surfaces,

and

and  , on the same rim,

, on the same rim,

|

(A.136) |

as illustrated in Figure A.23. (Note that the direction of the surface elements on  has been reversed relative to those on the closed surface. Hence, the

sign of the associated surface integral is also reversed.)

Thus, if

has been reversed relative to those on the closed surface. Hence, the

sign of the associated surface integral is also reversed.)

Thus, if

then the surface integral depends on the rim, but

not on the nature of the surface that spans it.

On the other hand, if

then the surface integral depends on the rim, but

not on the nature of the surface that spans it.

On the other hand, if

then the integral

depends on both the rim and the surface.

then the integral

depends on both the rim and the surface.

Figure A.23:

Two surfaces spanning the same rim (right), and the

equivalent closed surface (left).

|

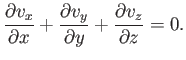

Consider an incompressible fluid whose velocity field is  . It is clear that

. It is clear that

for any closed surface, because what flows into the

surface must flow out again. Thus, according to the divergence theorem,

for any closed surface, because what flows into the

surface must flow out again. Thus, according to the divergence theorem,

for any volume. The only way in which this is

possible is if

for any volume. The only way in which this is

possible is if

is everywhere zero. Thus, the velocity components

of an incompressible fluid satisfy the following differential relation:

is everywhere zero. Thus, the velocity components

of an incompressible fluid satisfy the following differential relation:

|

(A.137) |

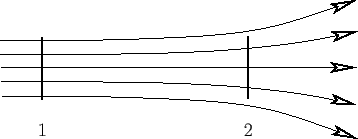

It is sometimes helpful to represent a vector field  by lines of force

or field-lines.

The direction of a line of force at any point is the same as the local direction of

by lines of force

or field-lines.

The direction of a line of force at any point is the same as the local direction of

. The density of lines (i.e., the number of lines crossing a unit surface

perpendicular to

. The density of lines (i.e., the number of lines crossing a unit surface

perpendicular to  ) is equal to

) is equal to  .

For instance, in Figure A.24,

.

For instance, in Figure A.24,  is larger at point 1 than at point 2. The number of lines

crossing a surface element

is larger at point 1 than at point 2. The number of lines

crossing a surface element  is

is

. So, the

net number of lines leaving a closed surface is

. So, the

net number of lines leaving a closed surface is

|

(A.138) |

If

then there is no net flux of lines out of any surface.

Such a field is

called a solenoidal vector field. The simplest example of a solenoidal vector

field is one in which the lines of force all form closed loops.

then there is no net flux of lines out of any surface.

Such a field is

called a solenoidal vector field. The simplest example of a solenoidal vector

field is one in which the lines of force all form closed loops.

Figure A.24:

Divergent lines of force.

|

Next: Laplacian Operator

Up: Vectors and Vector Fields

Previous: Grad Operator

Richard Fitzpatrick

2016-01-22

![]() is constant in space then it is easily demonstrated that the net

flux out of

is constant in space then it is easily demonstrated that the net

flux out of ![]() is zero. In fact,

is zero. In fact,

![]() is not uniform in space. Consider a very small

rectangular volume over which

is not uniform in space. Consider a very small

rectangular volume over which ![]() hardly varies. The contribution to

hardly varies. The contribution to

![]() from the two faces normal to the

from the two faces normal to the ![]() -axis is

-axis is

![]() surrounded by a closed surface

surrounded by a closed surface ![]() ,

,

![]() ,

,

![]() . It is clear that

. It is clear that

![]() for any closed surface, because what flows into the

surface must flow out again. Thus, according to the divergence theorem,

for any closed surface, because what flows into the

surface must flow out again. Thus, according to the divergence theorem,

![]() for any volume. The only way in which this is

possible is if

for any volume. The only way in which this is

possible is if

![]() is everywhere zero. Thus, the velocity components

of an incompressible fluid satisfy the following differential relation:

is everywhere zero. Thus, the velocity components

of an incompressible fluid satisfy the following differential relation:

![]() by lines of force

or field-lines.

The direction of a line of force at any point is the same as the local direction of

by lines of force

or field-lines.

The direction of a line of force at any point is the same as the local direction of

![]() . The density of lines (i.e., the number of lines crossing a unit surface

perpendicular to

. The density of lines (i.e., the number of lines crossing a unit surface

perpendicular to ![]() ) is equal to

) is equal to ![]() .

For instance, in Figure A.24,

.

For instance, in Figure A.24, ![]() is larger at point 1 than at point 2. The number of lines

crossing a surface element

is larger at point 1 than at point 2. The number of lines

crossing a surface element ![]() is

is

![]() . So, the

net number of lines leaving a closed surface is

. So, the

net number of lines leaving a closed surface is