|

|

|

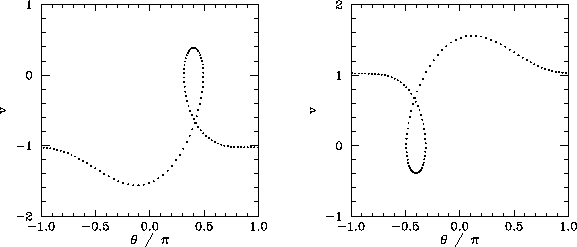

The interval

between the first and second chaotic regions is occupied by the period-1 orbits shown in

Fig. 59. Note that these orbits differ somewhat from previously encountered period-1 orbits,

because the pendulum executes a complete rotation (either to

the left or to the right) every period of the external drive.

Now, an ![]() periodic orbit is defined such that

periodic orbit is defined such that

|

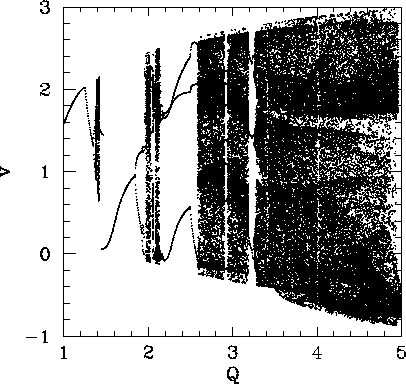

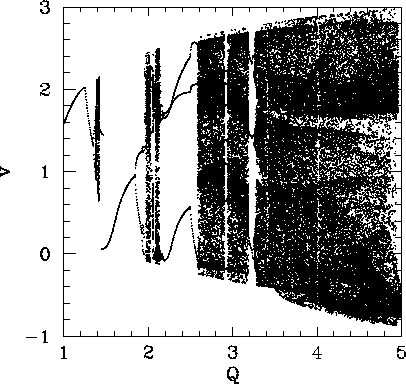

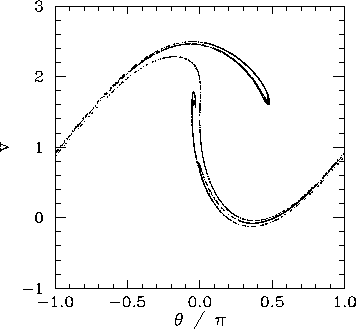

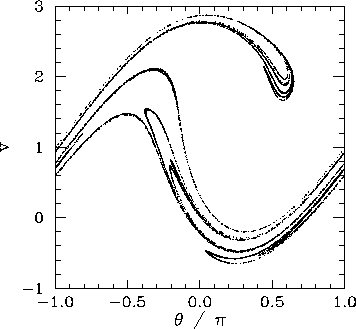

Figure 60 shows the Poincaré section of a typical attractor in the second chaotic region shown in Fig. 58. It can be seen that this attractor is far more convoluted and extensive than the simple 4-line chaotic attractor pictured in Fig. 48. In fact, the attractor shown in Fig. 60 is clearly a fractal curve. It turns out that virtually all chaotic attractors exhibit fractal structure.

The interval between the second and third chaotic regions shown in Fig. 58 is

occupied by ![]() ,

, ![]() periodic orbits. Figure 61 shows the Poincaré section

of a typical attractor in the

third chaotic region. It can be seen that this attractor is even more overtly fractal

in nature than that pictured in the previous figure. Note that the fractal nature

of chaotic attractors is closely associated with some of their unusual properties.

Trajectories on a chaotic attractor remain confined to a bounded region of phase-space,

and yet they separate from their neighbours exponentially fast (at least, initially).

How can trajectories diverge endlessly and still stay bounded? The basic mechanism

is described below.

If we imagine

a blob of initial conditions in phase-space, then these undergo a series of

repeated stretching and folding episodes, as the chaotic motion unfolds. The stretching is

what gives rise to the divergence of neighbouring trajectories. The folding is what ensures that

the trajectories remain bounded.

The net

result is a phase-space structure which looks a bit like filo dough--in other words, a fractal

structure.

periodic orbits. Figure 61 shows the Poincaré section

of a typical attractor in the

third chaotic region. It can be seen that this attractor is even more overtly fractal

in nature than that pictured in the previous figure. Note that the fractal nature

of chaotic attractors is closely associated with some of their unusual properties.

Trajectories on a chaotic attractor remain confined to a bounded region of phase-space,

and yet they separate from their neighbours exponentially fast (at least, initially).

How can trajectories diverge endlessly and still stay bounded? The basic mechanism

is described below.

If we imagine

a blob of initial conditions in phase-space, then these undergo a series of

repeated stretching and folding episodes, as the chaotic motion unfolds. The stretching is

what gives rise to the divergence of neighbouring trajectories. The folding is what ensures that

the trajectories remain bounded.

The net

result is a phase-space structure which looks a bit like filo dough--in other words, a fractal

structure.

|