Consider ![]() atoms in the presence of a

atoms in the presence of a ![]() -directed magnetic field of

strength

-directed magnetic field of

strength ![]() . Suppose that all

atoms are identical spin-

. Suppose that all

atoms are identical spin-![]() systems. It follows that either

systems. It follows that either ![]() (spin up) or

(spin up) or ![]() (spin down), where

(spin down), where ![]() is (twice) the

is (twice) the ![]() -component

of the

-component

of the ![]() th atomic spin. The total energy of the system is

written:

th atomic spin. The total energy of the system is

written:

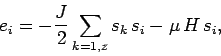

The physics of the Ising model is as follows. The first term on the right-hand

side of Eq. (351) shows that the overall energy is lowered when

neighbouring atomic spins are aligned. This effect is mostly

due to the Pauli exclusion principle. Electrons cannot occupy the same quantum

state, so two electrons on neighbouring atoms which have parallel spins

(i.e., occupy the same orbital state) cannot come close together in

space. No such restriction applies if the electrons have anti-parallel

spins. Different spatial separations imply different electrostatic

interaction energies, and the exchange energy, ![]() , measures this difference.

Note that since the exchange energy is electrostatic in origin, it

can be quite large: i.e.,

, measures this difference.

Note that since the exchange energy is electrostatic in origin, it

can be quite large: i.e., ![]() eV. This is far larger than the

energy associated with the direct magnetic interaction between neighbouring

atomic spins, which

is only about

eV. This is far larger than the

energy associated with the direct magnetic interaction between neighbouring

atomic spins, which

is only about ![]() eV. However, the exchange effect is very short-range; hence,

the restriction to nearest neighbour interaction is quite realistic.

eV. However, the exchange effect is very short-range; hence,

the restriction to nearest neighbour interaction is quite realistic.

Our first attempt to analyze the Ising model will employ a simplification

known as the mean field approximation. The energy of the ![]() th atom is written

th atom is written

|

(352) |

|

(353) |

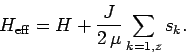

We can write

| (354) |

|

(355) |

Consider a single atom in a magnetic field ![]() . Suppose that

the atom is in thermal equilibrium with a heat bath of temperature

. Suppose that

the atom is in thermal equilibrium with a heat bath of temperature

![]() . According to the well-known Boltzmann distribution, the mean spin

of the atom is

. According to the well-known Boltzmann distribution, the mean spin

of the atom is

|

(356) |

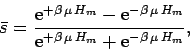

Let us assume that all atoms have identical spins: i.e., ![]() .

This assumption is known as the ``mean field approximation''.

We can write

.

This assumption is known as the ``mean field approximation''.

We can write

| (360) |

|

(361) |

| (362) |

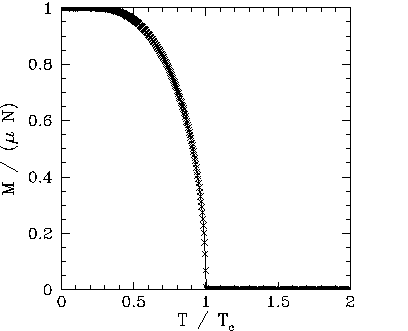

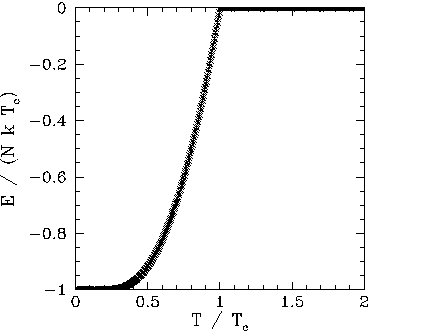

It is helpful to define the net magnetization,

|

(364) |

|

(365) |

| (366) |

|

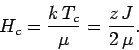

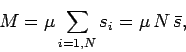

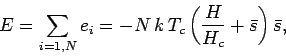

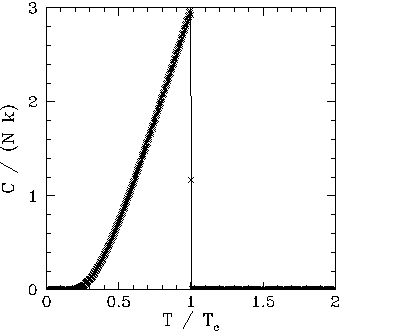

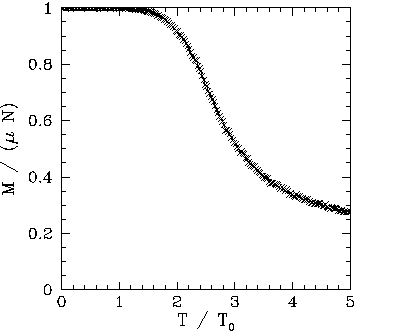

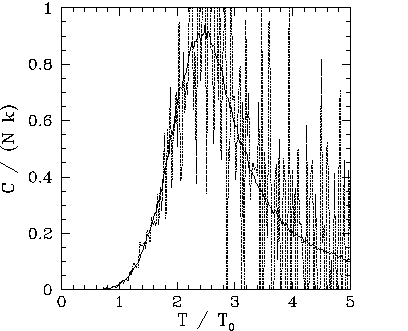

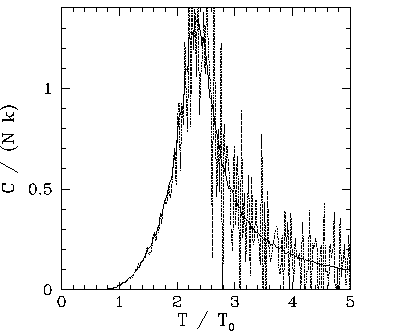

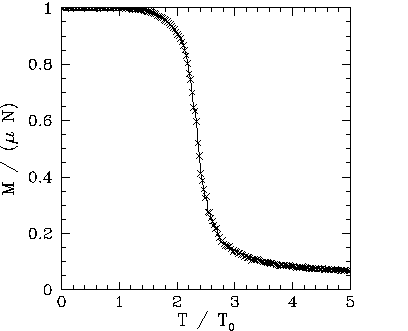

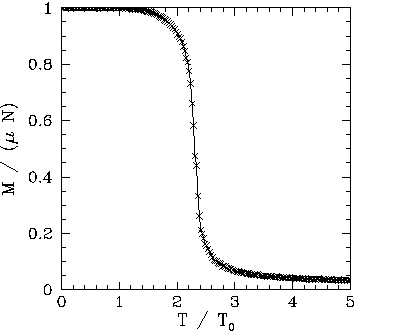

Figures 102, 101, and 103 show the net magnetization, net energy,

and heat capacity calculated from the iteration formula (363) in the

absence of an external magnetic field (i.e., with ![]() ). It

can be seen that below the critical (or ``Curie'') temperature,

). It

can be seen that below the critical (or ``Curie'') temperature, ![]() , there is

spontaneous magnetization: i.e., the exchange effect is sufficiently large

to cause neighbouring atomic spins to spontaneously align. On the other hand,

thermal fluctuations completely eliminate any alignment above the critical temperature. Moreover, at the

critical temperature there is a

discontinuity in the first derivative of the energy,

, there is

spontaneous magnetization: i.e., the exchange effect is sufficiently large

to cause neighbouring atomic spins to spontaneously align. On the other hand,

thermal fluctuations completely eliminate any alignment above the critical temperature. Moreover, at the

critical temperature there is a

discontinuity in the first derivative of the energy, ![]() , with respect to

the temperature,

, with respect to

the temperature, ![]() . This discontinuity generates a downward jump

in the heat capacity,

. This discontinuity generates a downward jump

in the heat capacity, ![]() , at

, at ![]() . The sudden loss of spontaneous

magnetization as the temperature exceeds the critical temperature is a type of

phase transition.

. The sudden loss of spontaneous

magnetization as the temperature exceeds the critical temperature is a type of

phase transition.

|

Now, according to the conventional classification of phase transitions, a transition is first-order if the energy is discontinuous with respect to the order parameter (i.e., in this case, the temperature), and second-order if the energy is continuous, but its first derivative with respect to the order parameter is discontinuous, etc. We conclude that the loss of spontaneous magnetization in a ferromagnetic material as the temperature exceeds the critical temperature is a second-order phase transition.

|

In order to see an example of a first-order phase transition, let us examine

the behaviour of the magnetization, ![]() , as the external field,

, as the external field, ![]() , is

varied at constant temperature,

, is

varied at constant temperature, ![]() .

.

|

|

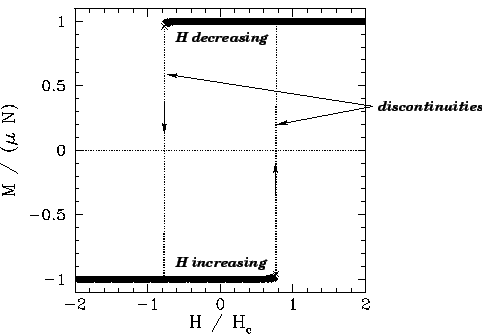

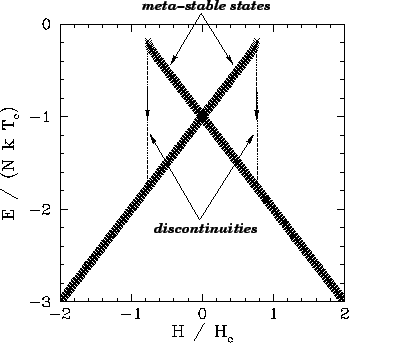

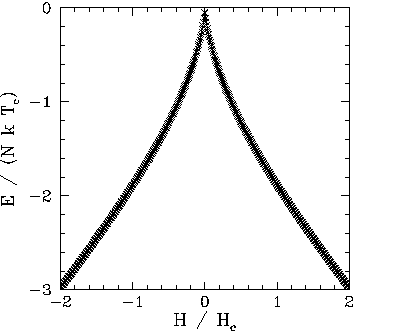

Figures 104 and 105 show the magnetization, ![]() , and energy,

, and energy, ![]() , versus

external field-strength,

, versus

external field-strength, ![]() , calculated from the iteration formula (363)

at some constant temperature,

, calculated from the iteration formula (363)

at some constant temperature, ![]() , which is less

than the critical temperature,

, which is less

than the critical temperature, ![]() . It can be seen that

. It can be seen that ![]() is

discontinuous, indicating the presence of a first-order phase transition.

Moreover, the system exhibits hysteresis--meta-stable

states exist within a certain range of

is

discontinuous, indicating the presence of a first-order phase transition.

Moreover, the system exhibits hysteresis--meta-stable

states exist within a certain range of ![]() values, and the magnetization of the system

at fixed

values, and the magnetization of the system

at fixed ![]() and

and ![]() (within the aforementioned range) depends on its past history:

i.e., on whether

(within the aforementioned range) depends on its past history:

i.e., on whether ![]() was increasing or decreasing when it entered the meta-stable

range.

was increasing or decreasing when it entered the meta-stable

range.

|

|

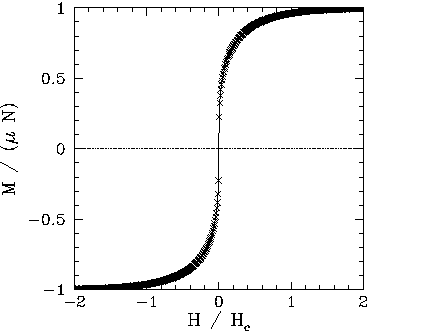

Figures 106 and 107 show the magnetization, ![]() , and energy,

, and energy, ![]() , versus

external field-strength,

, versus

external field-strength, ![]() , calculated from the iteration formula (363)

at a constant temperature,

, calculated from the iteration formula (363)

at a constant temperature, ![]() , which is equal to the critical temperature,

, which is equal to the critical temperature, ![]() .

It can be seen that

.

It can be seen that ![]() is now

continuous, and there are no meta-stable states. We conclude that first-order

phase transitions and hysteresis only occur, as the external field-strength is varied, when the

temperature lies below the critical temperature: i.e., when the ferromagnetic

material in question is capable of spontaneous magnetization.

is now

continuous, and there are no meta-stable states. We conclude that first-order

phase transitions and hysteresis only occur, as the external field-strength is varied, when the

temperature lies below the critical temperature: i.e., when the ferromagnetic

material in question is capable of spontaneous magnetization.

The above calculations, which are based on the mean field approximation, correctly predict

the existence of first- and second-order phase transitions when ![]() and

and ![]() ,

respectively. However, these calculations get some of the details of the second-order

phase transition wrong. In order to do a better job, we must abandon the mean

field approximation and

adopt a Monte-Carlo approach.

,

respectively. However, these calculations get some of the details of the second-order

phase transition wrong. In order to do a better job, we must abandon the mean

field approximation and

adopt a Monte-Carlo approach.

Let us consider a two-dimensional square array of atoms. Let ![]() be the

size of the array, and

be the

size of the array, and ![]() the number of atoms in the array, as shown in

Fig. 108. The Monte-Carlo approach to the Ising model, which completely avoids

the use of the mean field approximation, is based on the following

algorithm:

the number of atoms in the array, as shown in

Fig. 108. The Monte-Carlo approach to the Ising model, which completely avoids

the use of the mean field approximation, is based on the following

algorithm:

In order to demonstrate that the above algorithm is correct, let us consider

flipping the spin of the ![]() th atom. Suppose that this operation causes the

system to make a transition from state

th atom. Suppose that this operation causes the

system to make a transition from state ![]() (energy,

(energy, ![]() ) to state

) to state ![]() (energy,

(energy, ![]() ).

Suppose, further, that

).

Suppose, further, that ![]() . According to the above algorithm, the probability

of a transition from state

. According to the above algorithm, the probability

of a transition from state ![]() to state

to state ![]() is

is

| (367) |

| (368) |

| (370) |

Now, each atom in our array has four nearest neighbours, except for atoms on the edge of the array, which have less than four neighbours. We can eliminate this annoying special behaviour by adopting periodic boundary conditions: i.e., by identifying opposite edges of the array. Indeed, we can think of the array as existing on the surface of a torus.

It is helpful to define

| (371) |

| (372) |

|

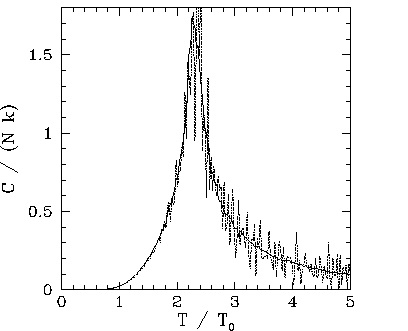

Figures 109-116 show magnetization and heat capacity versus temperature

curves for ![]() , 10, 20, and 40 in the absence of an

external magnetic field. In all cases, the Monte-Carlo simulation is iterated 5000 times,

and the first 1000 iterations are discarded when evaluating

, 10, 20, and 40 in the absence of an

external magnetic field. In all cases, the Monte-Carlo simulation is iterated 5000 times,

and the first 1000 iterations are discarded when evaluating ![]() (in order to

allow the system to attain thermal equilibrium). The two-dimensional array of atoms is

initialized in a fully aligned state for each different value of the temperature. Since there is

no external magnetic field, it is irrelevant whether the magnetization, M, is

positive or negative. Hence,

(in order to

allow the system to attain thermal equilibrium). The two-dimensional array of atoms is

initialized in a fully aligned state for each different value of the temperature. Since there is

no external magnetic field, it is irrelevant whether the magnetization, M, is

positive or negative. Hence, ![]() is replaced by

is replaced by ![]() in all plots.

in all plots.

|

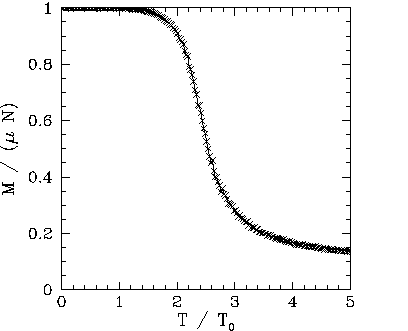

Note that the ![]() versus

versus ![]() curves generated by the Monte-Carlo simulations

look very much like those predicted by the

mean field model. The resemblance increases as the size,

curves generated by the Monte-Carlo simulations

look very much like those predicted by the

mean field model. The resemblance increases as the size, ![]() , of the atomic

array increases. The major difference is the presence of a magnetization ``tail'' for

, of the atomic

array increases. The major difference is the presence of a magnetization ``tail'' for ![]() in

the Monte-Carlo simulations: i.e., in the Monte-Carlo simulations the spontaneous magnetization

does not collapse to zero once the critical temperature is exceeded--there is

a small lingering magnetization for

in

the Monte-Carlo simulations: i.e., in the Monte-Carlo simulations the spontaneous magnetization

does not collapse to zero once the critical temperature is exceeded--there is

a small lingering magnetization for ![]() .

The

.

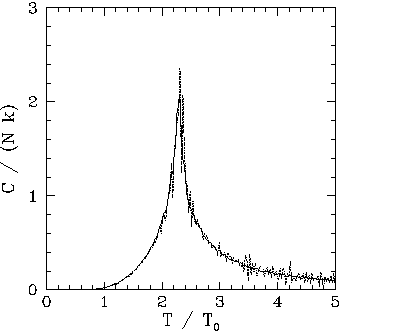

The ![]() versus

versus ![]() curves show the heat capacity calculated directly (i.e.,

curves show the heat capacity calculated directly (i.e.,

![]() ),

and via the identity

),

and via the identity

![]() . The latter method of calculation is

clearly far superior, since it generates significantly less statistical noise. Note that the heat capacity

peaks at the critical temperature: i.e., unlike the mean field model,

. The latter method of calculation is

clearly far superior, since it generates significantly less statistical noise. Note that the heat capacity

peaks at the critical temperature: i.e., unlike the mean field model, ![]() is

not zero for

is

not zero for ![]() . This effect is due to the residual magnetization present when

. This effect is due to the residual magnetization present when ![]() .

.

|

Our best estimate for ![]() is obtained from the location of the peak in the

is obtained from the location of the peak in the ![]() versus

versus ![]() curve in Fig. 116. We obtain

curve in Fig. 116. We obtain ![]() . Recall that the mean field model

yields

. Recall that the mean field model

yields ![]() . The exact answer for a two-dimensional array of ferromagnetic atoms

is

. The exact answer for a two-dimensional array of ferromagnetic atoms

is

|

(375) |

|

Note, from Figs. 110, 112, 114, and 116, that the height of the peak in the heat capacity curve at ![]() increases with increasing array

size,

increases with increasing array

size, ![]() . Indeed, a close examination of these figures yields

. Indeed, a close examination of these figures yields

![]() for

for ![]() ,

,

![]() for

for ![]() ,

,

![]() for

for ![]() , and

, and

![]() for

for ![]() .

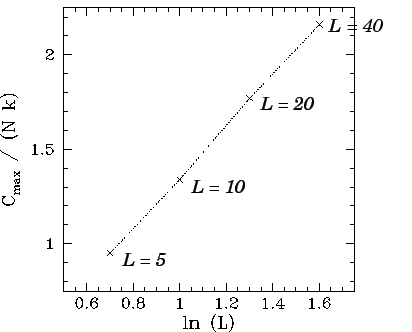

Figure 117 shows

.

Figure 117 shows

![]() plotted against

plotted against ![]() for

for ![]() , 10, 20, and 40.

It can be seen that the points lie on a very convincing straight-line, which strongly suggests that

, 10, 20, and 40.

It can be seen that the points lie on a very convincing straight-line, which strongly suggests that

| (376) |

|

Of course, for physical systems,

![]() , where

, where ![]() is Avogadro's

number. Hence,

is Avogadro's

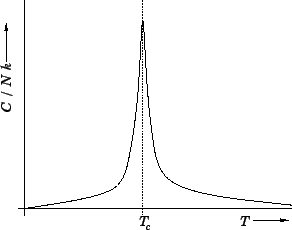

number. Hence, ![]() is effectively singular at the critical temperature

(since

is effectively singular at the critical temperature

(since ![]() ), as sketched in

Fig. 118. This observation leads us to revise our definition of a second-order phase

transition. It turns out that actual discontinuities in the heat capacity almost

never occur. Instead, second-order phase transitions are

characterized by a local quasi-singularity in the heat capacity.

), as sketched in

Fig. 118. This observation leads us to revise our definition of a second-order phase

transition. It turns out that actual discontinuities in the heat capacity almost

never occur. Instead, second-order phase transitions are

characterized by a local quasi-singularity in the heat capacity.

|

Recall, from Eq. (374), that the typical amplitude of energy fluctuations is proportional

to the square-root of the heat capacity (i.e.,

![]() ). It

follows that the amplitude of energy fluctuations becomes extremely large in the vicinity

of a second-order phase transition.

). It

follows that the amplitude of energy fluctuations becomes extremely large in the vicinity

of a second-order phase transition.

|

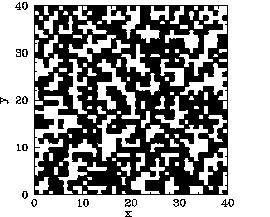

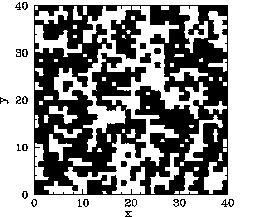

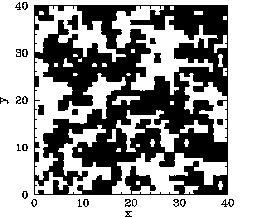

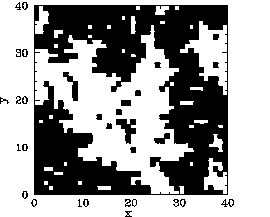

Now, the main difference between our mean field and Monte-Carlo calculations is the existence

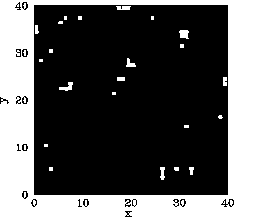

of residual magnetization for ![]() in the latter case. Figures 119-123

show the magnetization pattern of a

in the latter case. Figures 119-123

show the magnetization pattern of a ![]() array of ferromagnetic atoms, in thermal

equilibrium and in the absence of an external magnetic field, calculated at various temperatures.

It can be seen that for

array of ferromagnetic atoms, in thermal

equilibrium and in the absence of an external magnetic field, calculated at various temperatures.

It can be seen that for ![]() the pattern is essentially random. However,

for

the pattern is essentially random. However,

for ![]() , small clumps appear in the pattern. For

, small clumps appear in the pattern. For ![]() , the clumps

are somewhat bigger. For

, the clumps

are somewhat bigger. For ![]() , which is just above the critical temperature,

the clumps are global in extent. Finally, for

, which is just above the critical temperature,

the clumps are global in extent. Finally, for ![]() , which is a little

below the critical temperature, there is almost complete alignment of the atomic spins.

, which is a little

below the critical temperature, there is almost complete alignment of the atomic spins.

|

The problem with the mean field model is that it assumes that all atoms are situated in identical environments. Hence, if the exchange effect is not sufficiently large to cause global alignment of the atomic spins then there is no alignment at all. What actually happens when the temperature exceeds the critical temperature is that global alignment disappears, but local alignment (i.e., clumping) remains. Clumps are only eliminated by thermal fluctuations once the temperature is significantly greater than the critical temperature. Atoms in the middle of the clumps are situated in a different environment than atoms on the clump boundaries. Hence, clumps cannot occur in the mean field model.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|