Next: Two Coupled LC Circuits Up: Coupled Oscillations Previous: Introduction Contents

that are free to slide over a frictionless horizontal surface. Suppose that

the masses are attached to one another, and to two immovable

walls, by means of three identical light horizontal springs of spring constant

that are free to slide over a frictionless horizontal surface. Suppose that

the masses are attached to one another, and to two immovable

walls, by means of three identical light horizontal springs of spring constant  , as

shown in Figure 3.1. The instantaneous state of the system

is conveniently specified by the displacements of the left and

right masses,

, as

shown in Figure 3.1. The instantaneous state of the system

is conveniently specified by the displacements of the left and

right masses,  and

and  , respectively. The extensions

of the left, middle, and right springs are

, respectively. The extensions

of the left, middle, and right springs are  ,

,  , and

, and  ,

respectively, assuming that

,

respectively, assuming that  corresponds to the equilibrium configuration in which the springs are all

unextended. The equations of motion of the two masses

are thus

Here, we have made use of the fact that a mass attached to the left end of a

spring of extension

corresponds to the equilibrium configuration in which the springs are all

unextended. The equations of motion of the two masses

are thus

Here, we have made use of the fact that a mass attached to the left end of a

spring of extension  and spring constant

and spring constant  experiences a horizontal force

experiences a horizontal force  ,

whereas a mass attached to the right end of the same spring experiences an

equal and opposite force

,

whereas a mass attached to the right end of the same spring experiences an

equal and opposite force  .

.

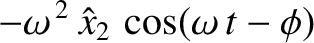

Equations (3.1)–(3.2) can be rewritten in the form

where . Let us search for a solution in which the two

masses oscillate in phase with one another at the same angular frequency,

. Let us search for a solution in which the two

masses oscillate in phase with one another at the same angular frequency,  . In other words,

where

. In other words,

where  ,

,  , and

, and  are constants. Equations (3.3) and

(3.4) yield

are constants. Equations (3.3) and

(3.4) yield

|

|

(3.7) |

|

|

(3.8) |

, dividing through by

, dividing through by  , and rearranging),

where

, and rearranging),

where

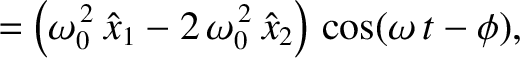

. Note that, by searching for a solution

of the form (3.5)–(3.6), we have effectively converted the system of two coupled

linear differential equations (3.3)–(3.4) into the much simpler system of two coupled linear algebraic

equations (3.9)–(3.10). The latter equations have the trivial solutions

. Note that, by searching for a solution

of the form (3.5)–(3.6), we have effectively converted the system of two coupled

linear differential equations (3.3)–(3.4) into the much simpler system of two coupled linear algebraic

equations (3.9)–(3.10). The latter equations have the trivial solutions

, but also yield

Hence, the condition for a nontrivial solution is

In fact, if we write Equations (3.9)–(3.10) in the form of a homogenous (i.e., with a null right-hand side)

, but also yield

Hence, the condition for a nontrivial solution is

In fact, if we write Equations (3.9)–(3.10) in the form of a homogenous (i.e., with a null right-hand side)  matrix equation, so that

matrix equation, so that

![\begin{displaymath}\left(

\begin{array}{cc}

\hat{\omega}^{\,2}-2, & 1\\ [0.5ex]

...

...t) = \left(

\begin{array}{c}

0\\ [0.5ex] 0

\end{array}\right) ,\end{displaymath}](img687.png) |

(3.13) |

Equation (3.12) can be rewritten

It follows that or or  |

(3.15) |

and

and

—because a negative frequency oscillation

is equivalent to an oscillation with an equal and opposite positive frequency, and

an equal and opposite phase. In other words,

—because a negative frequency oscillation

is equivalent to an oscillation with an equal and opposite positive frequency, and

an equal and opposite phase. In other words,

.

It is thus apparent that

the dynamical system pictured in Figure 3.1 has two unique frequencies of oscillation: namely,

.

It is thus apparent that

the dynamical system pictured in Figure 3.1 has two unique frequencies of oscillation: namely,

and

and

. These are called the normal frequencies of the

system.

Because the system possesses two degrees of

freedom (i.e., two independent coordinates are needed to specify its

instantaneous configuration), it is not entirely surprising that it possesses two

normal frequencies. In fact, it is a general rule that a dynamical system

with

. These are called the normal frequencies of the

system.

Because the system possesses two degrees of

freedom (i.e., two independent coordinates are needed to specify its

instantaneous configuration), it is not entirely surprising that it possesses two

normal frequencies. In fact, it is a general rule that a dynamical system

with  degrees of freedom possesses

degrees of freedom possesses  normal frequencies.

normal frequencies.

The patterns of motion associated with the two normal frequencies

can be deduced from Equation (3.11). Thus, for

(i.e.,

(i.e.,

), we

get

), we

get

, so that

, so that

and

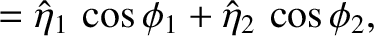

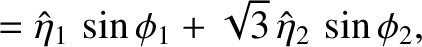

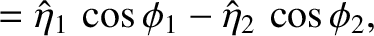

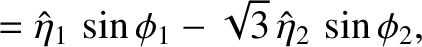

and  are arbitrary constants. This first pattern of motion corresponds to the two masses

executing simple harmonic oscillation with the same amplitude and phase.

Such an oscillation does not stretch the middle spring.

On the other hand, for

are arbitrary constants. This first pattern of motion corresponds to the two masses

executing simple harmonic oscillation with the same amplitude and phase.

Such an oscillation does not stretch the middle spring.

On the other hand, for

(i.e.,

(i.e.,

), we get

), we get

, so that

where

, so that

where

and

and  are arbitrary constants. This second pattern of motion

corresponds to the two masses executing simple harmonic oscillation with the

same amplitude but in anti-phase; that is, with a phase shift of

are arbitrary constants. This second pattern of motion

corresponds to the two masses executing simple harmonic oscillation with the

same amplitude but in anti-phase; that is, with a phase shift of  radians. Such oscillations do stretch the

middle spring, implying that the restoring force associated with

similar amplitude displacements is greater for the second

pattern of motion than for the first. This accounts for the higher

oscillation frequency in the second case. (The inertia is the same in both cases, so the

oscillation frequency is proportional to the square root of the restoring force

associated with similar amplitude displacements.) The two distinctive

patterns of motion that we have found are called the normal modes of

oscillation of the system. Incidentally, it is a general rule that a dynamical system

possessing

radians. Such oscillations do stretch the

middle spring, implying that the restoring force associated with

similar amplitude displacements is greater for the second

pattern of motion than for the first. This accounts for the higher

oscillation frequency in the second case. (The inertia is the same in both cases, so the

oscillation frequency is proportional to the square root of the restoring force

associated with similar amplitude displacements.) The two distinctive

patterns of motion that we have found are called the normal modes of

oscillation of the system. Incidentally, it is a general rule that a dynamical system

possessing  degrees of freedom has

degrees of freedom has  unique normal modes of oscillation.

unique normal modes of oscillation.

The most general motion of the system is a

linear combination of the two normal modes. This immediately follows because

Equations (3.1) and (3.2) are linear equations. [In other

words, if  and

and  are solutions then so are

are solutions then so are

and

and

,

where

,

where  is an arbitrary constant.] Thus, we can write

is an arbitrary constant.] Thus, we can write

,

,  ,

,

, and

, and  . (In general,

we expect the solution of a second-order ordinary differential equation to

contain two arbitrary constants. It, thus, follows that the solution of a system of two

coupled, second-order, ordinary differential equations should contain four arbitrary constants.)

These constants are determined by the initial conditions.

. (In general,

we expect the solution of a second-order ordinary differential equation to

contain two arbitrary constants. It, thus, follows that the solution of a system of two

coupled, second-order, ordinary differential equations should contain four arbitrary constants.)

These constants are determined by the initial conditions.

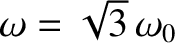

For instance, suppose that  ,

,

,

,  , and

, and

at

at  . It follows, from Equations (3.20) and (3.21), that

. It follows, from Equations (3.20) and (3.21), that

|

|

(3.22) |

| 0 |  |

(3.23) |

| 0 |  |

(3.24) |

| 0 |  |

(3.25) |

and

and

. Thus, the

system evolves in time as

. Thus, the

system evolves in time as

|

|

(3.26) |

|

|

(3.27) |

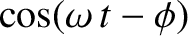

![$\omega_\pm = [(\sqrt{3}\pm 1)/2]]\,\omega_0$](img722.png) , and

use has been made of the trigonometric identities

, and

use has been made of the trigonometric identities

![$\cos a + \cos b\equiv 2\,\cos[(a+b)/2]\,\cos[(a-b)/2]$](img723.png) and

and

![$\cos a - \cos b \equiv -2\,\sin[(a+b)/2]\,\sin[(a-b)/2]$](img620.png) . (See Appendix B.) This evolution is

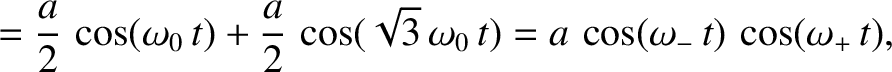

illustrated in Figure 3.2.

. (See Appendix B.) This evolution is

illustrated in Figure 3.2.

![\includegraphics[width=0.8\textwidth]{Chapter03/fig3_02.eps}](img724.png) |

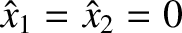

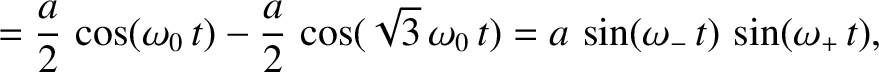

Finally, let us define the so-called normal coordinates, which (in the present case) take the form

|

![$\displaystyle = [x_1(t) + x_2(t)]/2,$](img727.png) |

(3.28) |

|

![$\displaystyle = [x_1(t)-x_2(t)]/2.$](img729.png) |

(3.29) |

and

and  . See Figures 3.2 and 3.3.

This suggests that the equations of motion of the system should look particularly simple when expressed in terms of the normal coordinates. In fact, it

can be seen that the

sum of Equations (3.3) and (3.4) reduces to

whereas the difference gives

Thus, when expressed in terms of the normal coordinates, the equations of motion

of the system reduce to two uncoupled simple harmonic oscillator

equations.

The most general solution to Equation (3.32) is (3.30),

whereas the most general solution to Equation (3.33) is (3.31).

Hence, if we can guess the normal coordinates of a coupled oscillatory

system then the determination of the normal modes of oscillation is considerably simplified.

. See Figures 3.2 and 3.3.

This suggests that the equations of motion of the system should look particularly simple when expressed in terms of the normal coordinates. In fact, it

can be seen that the

sum of Equations (3.3) and (3.4) reduces to

whereas the difference gives

Thus, when expressed in terms of the normal coordinates, the equations of motion

of the system reduce to two uncoupled simple harmonic oscillator

equations.

The most general solution to Equation (3.32) is (3.30),

whereas the most general solution to Equation (3.33) is (3.31).

Hence, if we can guess the normal coordinates of a coupled oscillatory

system then the determination of the normal modes of oscillation is considerably simplified.

Note that, in general, the normal coordinates of a multiple-degree-of-freedom oscillatory system are linear combinations of the physical coordinates. By definition, the equations of motion of the system become decoupled from one another when expressed in terms of the normal coordinates. In fact, each equation of motion takes the form of a simple harmonic oscillator equation whose characteristic frequency is one of the normal frequencies. Consequently, each normal coordinate executes simple harmonic oscillation at its associated normal frequency.

![\includegraphics[width=0.8\textwidth]{Chapter03/fig3_03.eps}](img734.png) |