Next: Compound Pendulum Up: Simple Harmonic Oscillation Previous: LC Circuit Contents

Consider a compact mass  suspended from a light inextensible string of length

suspended from a light inextensible string of length  , such that the

mass is free to swing from side to side in a vertical plane, as shown in

Figure 1.8.

This setup is known as a simple pendulum.

Let

, such that the

mass is free to swing from side to side in a vertical plane, as shown in

Figure 1.8.

This setup is known as a simple pendulum.

Let  be the angle subtended between the string and

the downward vertical. The stable equilibrium state of the system corresponds to

the situation in which the mass is stationary, and hangs vertically down (

i.e.,

be the angle subtended between the string and

the downward vertical. The stable equilibrium state of the system corresponds to

the situation in which the mass is stationary, and hangs vertically down (

i.e.,

).

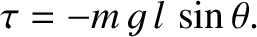

The angular equation of motion of the pendulum is (Fowles and Cassiday 2005)

).

The angular equation of motion of the pendulum is (Fowles and Cassiday 2005)

|

(1.48) |

is the moment of inertia of the mass, and

is the moment of inertia of the mass, and  the torque acting

about the suspension point.

For the

case in hand, given that the mass is essentially a point particle, and is situated a distance

the torque acting

about the suspension point.

For the

case in hand, given that the mass is essentially a point particle, and is situated a distance  from

the axis of rotation (i.e., from the suspension point), it follows that

from

the axis of rotation (i.e., from the suspension point), it follows that

(ibid.).

(ibid.).

The two forces acting on the mass are the downward gravitational force,  , where

, where  is the acceleration due to gravity,

and the tension,

is the acceleration due to gravity,

and the tension,  , in the string.

However, the tension makes no contribution to the torque,

because its line of action passes

through the suspension point. From elementary trigonometry,

the line of action of the gravitational force passes a perpendicular distance

, in the string.

However, the tension makes no contribution to the torque,

because its line of action passes

through the suspension point. From elementary trigonometry,

the line of action of the gravitational force passes a perpendicular distance

from the

suspension point. Hence, the magnitude of the gravitational torque is

from the

suspension point. Hence, the magnitude of the gravitational torque is

.

Moreover, the gravitational torque is a restoring torque; that is, if

the mass is

displaced slightly from its equilibrium position (i.e.,

.

Moreover, the gravitational torque is a restoring torque; that is, if

the mass is

displaced slightly from its equilibrium position (i.e.,  ) then the

gravitational torque acts

to push the mass back toward that position. Thus, we can write

) then the

gravitational torque acts

to push the mass back toward that position. Thus, we can write

|

(1.49) |

, where

, where  is an arbitrary constant], which means that it is generally

very difficult to solve.

is an arbitrary constant], which means that it is generally

very difficult to solve.

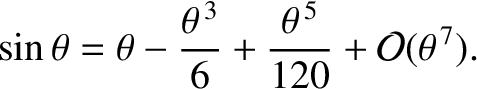

Suppose, however, that the system does not stray very far from

its equilibrium position ( ). If this is the case then we

can expand

). If this is the case then we

can expand

in a Taylor series about

in a Taylor series about  . (See Appendix B.) We obtain

. (See Appendix B.) We obtain

|

(1.51) |

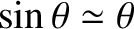

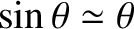

is sufficiently small then the series is dominated by its

first term, and we can write

is sufficiently small then the series is dominated by its

first term, and we can write

. This is known

as the small-angle approximation.

Making use of this approximation,

the equation of motion (1.50) simplifies to

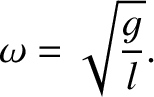

where

. This is known

as the small-angle approximation.

Making use of this approximation,

the equation of motion (1.50) simplifies to

where

|

(1.53) |

and

and  are constants.

We conclude that the pendulum swings back and forth at a fixed angular frequency,

are constants.

We conclude that the pendulum swings back and forth at a fixed angular frequency,  , that depends on

, that depends on  and

and  , but is independent of the amplitude,

, but is independent of the amplitude,

, of the motion. This result only holds as long as

the small-angle approximation remains valid. It turns out that

, of the motion. This result only holds as long as

the small-angle approximation remains valid. It turns out that

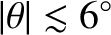

is a reasonably good approximation provided

is a reasonably good approximation provided

. Hence, the period

of a simple pendulum is only amplitude independent when the (angular) amplitude of its motion

is less than about

. Hence, the period

of a simple pendulum is only amplitude independent when the (angular) amplitude of its motion

is less than about  .

.