Next: Normal Modes of Uniform Up: Transverse Standing Waves Previous: Introduction Contents

identical beads of

mass

identical beads of

mass  are attached to the string in such a manner that they cannot slide along it. Let the beads be equally

spaced a distance

are attached to the string in such a manner that they cannot slide along it. Let the beads be equally

spaced a distance  apart, and let the distance between the first and the last beads and

the neighboring walls also be

apart, and let the distance between the first and the last beads and

the neighboring walls also be  . See Figure 4.1. Consider transverse

oscillations of the string; that is, oscillations in which the string

moves in a direction perpendicular to its length.

It is assumed that the inertia of the string

is negligible with respect to that of the beads. It follows that the sections of the string

between neighboring beads, and between the outermost beads and the walls,

are straight. (Otherwise, there would be a net tension force acting on the sections, and

they would consequently suffer an infinite acceleration.) In fact, we expect the instantaneous configuration of the string to be a

set of continuous straight-line segments of varying inclinations, as shown in the figure. Finally, assuming that

the transverse displacement of the string is relatively small, it is

reasonable to suppose that each section of the string possesses the

same tension,

. See Figure 4.1. Consider transverse

oscillations of the string; that is, oscillations in which the string

moves in a direction perpendicular to its length.

It is assumed that the inertia of the string

is negligible with respect to that of the beads. It follows that the sections of the string

between neighboring beads, and between the outermost beads and the walls,

are straight. (Otherwise, there would be a net tension force acting on the sections, and

they would consequently suffer an infinite acceleration.) In fact, we expect the instantaneous configuration of the string to be a

set of continuous straight-line segments of varying inclinations, as shown in the figure. Finally, assuming that

the transverse displacement of the string is relatively small, it is

reasonable to suppose that each section of the string possesses the

same tension,  . [See Equation (4.11).]

. [See Equation (4.11).]

It is convenient to introduce a Cartesian coordinate system such that  measures distance along the string from the left wall, and

measures distance along the string from the left wall, and

measures the transverse displacement of the string from its

equilibrium position. See Figure 4.1. Thus, when the string is in its equilibrium position

it runs along the

measures the transverse displacement of the string from its

equilibrium position. See Figure 4.1. Thus, when the string is in its equilibrium position

it runs along the  -axis. We can define

-axis. We can define

. Here,

. Here,  is the

is the  -coordinate of the

closest bead to the left wall,

-coordinate of the

closest bead to the left wall,  the

the

-coordinate of the second-closest bead, et cetera. The

-coordinate of the second-closest bead, et cetera. The  -coordinates of the beads

are assumed to remain constant during their transverse oscillations.

We can also define

-coordinates of the beads

are assumed to remain constant during their transverse oscillations.

We can also define  and

and

as the

as the  -coordinates of the left

and right ends of the string, respectively. Let the transverse displacement

of the

-coordinates of the left

and right ends of the string, respectively. Let the transverse displacement

of the  th bead be

th bead be  , for

, for  . Because each displacement

can vary independently, we are dealing with an

. Because each displacement

can vary independently, we are dealing with an  degree of freedom system.

We would, therefore, expect such a system to possess

degree of freedom system.

We would, therefore, expect such a system to possess  unique normal modes of

oscillation.

unique normal modes of

oscillation.

Consider the section of the

string lying between the  th and

th and  th beads, as shown in Figure 4.2.

Here,

th beads, as shown in Figure 4.2.

Here,

,

,  , and

, and

are the distances of the

are the distances of the  th,

th,  th, and

th, and

th beads, respectively,

from the left wall, whereas

th beads, respectively,

from the left wall, whereas  ,

,  , and

, and

are the corresponding transverse displacements of these beads.

The two sections of the string that are attached to the

are the corresponding transverse displacements of these beads.

The two sections of the string that are attached to the  th

bead subtend angles

th

bead subtend angles  and

and

with the

with the  -axis, as illustrated

in the figure. Standard trigonometry reveals that

-axis, as illustrated

in the figure. Standard trigonometry reveals that

|

(4.2) |

|

(4.3) |

for all

for all  —which we shall assume to be

the case, then

—which we shall assume to be

the case, then  and

and

are both small angles. Thus,

we can use the small-angle approximation

are both small angles. Thus,

we can use the small-angle approximation

. (See Appendix B.) It follows that

. (See Appendix B.) It follows that

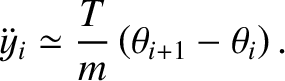

Let us find the transverse equation of motion of the  th bead. This

bead is subject to two forces: namely, the tensions in the sections

of the string to the left and to the right of it. (Incidentally, we are neglecting any gravitational forces

acting on the beads, compared to the tension forces.) These tensions are of

magnitude

th bead. This

bead is subject to two forces: namely, the tensions in the sections

of the string to the left and to the right of it. (Incidentally, we are neglecting any gravitational forces

acting on the beads, compared to the tension forces.) These tensions are of

magnitude  , and are directed parallel to the associated string sections, as shown

in Figure 4.2. Thus, the transverse (i.e.,

, and are directed parallel to the associated string sections, as shown

in Figure 4.2. Thus, the transverse (i.e.,  -directed) components of

these two tensions are

-directed) components of

these two tensions are

and

and

, respectively.

Hence, the transverse equation of motion of the

, respectively.

Hence, the transverse equation of motion of the  th bead becomes

th bead becomes

|

(4.6) |

and

and

are both small angles, we

can employ the small-angle approximation

are both small angles, we

can employ the small-angle approximation

.

It follows that

.

It follows that

|

(4.7) |

. Because there is nothing special

about the

. Because there is nothing special

about the  th bead, we deduce that the preceding equation of motion

applies to all

th bead, we deduce that the preceding equation of motion

applies to all  beads; that is, it is valid for

beads; that is, it is valid for  . Of course,

the first (

. Of course,

the first ( ) and last (

) and last ( ) beads are special cases, because there

is no bead corresponding to

) beads are special cases, because there

is no bead corresponding to  or

or  . In fact,

. In fact,  and

and  correspond to the left and right ends of the string, respectively. However,

Equation (4.8) still applies to the first and last beads, as long as

we set

correspond to the left and right ends of the string, respectively. However,

Equation (4.8) still applies to the first and last beads, as long as

we set  and

and  . What we are effectively demanding

is that the two ends of the string, which are attached to the left and right walls, must both have zero transverse

displacement.

. What we are effectively demanding

is that the two ends of the string, which are attached to the left and right walls, must both have zero transverse

displacement.

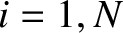

Incidentally, we can prove that the tensions in the two sections of the string shown in Figure 4.2 must be

equal by considering the longitudinal equation of motion of the  th bead. This equation takes the

form

th bead. This equation takes the

form

|

(4.9) |

and

and  are the, supposedly different, tensions in the sections of the string to the

immediate left and right of the

are the, supposedly different, tensions in the sections of the string to the

immediate left and right of the  th bead, respectively. We are assuming that the motion

of the beads is purely transverse; that is, all of the

th bead, respectively. We are assuming that the motion

of the beads is purely transverse; that is, all of the  are constant in time. Thus, it follows from the

preceding equation that

are constant in time. Thus, it follows from the

preceding equation that

|

(4.10) |

are small then

we can make use of the small-angle approximation

are small then

we can make use of the small-angle approximation

. (See Appendix B.) Hence, we

obtain

A straightforward extension of this argument reveals that the tension is the same in all sections of the string.

. (See Appendix B.) Hence, we

obtain

A straightforward extension of this argument reveals that the tension is the same in all sections of the string.

Let us search for a normal mode solution to Equation (4.8) that takes the form

where ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  are constants.

This particular type of solution is such that all of the beads execute transverse simple harmonic oscillations

that are in phase

with one another. See Figure 4.4. Moreover, the oscillations have an amplitude

are constants.

This particular type of solution is such that all of the beads execute transverse simple harmonic oscillations

that are in phase

with one another. See Figure 4.4. Moreover, the oscillations have an amplitude

that varies sinusoidally along the length of the string (i.e., in the

that varies sinusoidally along the length of the string (i.e., in the  -direction). The pattern of oscillations is thus periodic in space. The spatial repetition period, which is generally termed the wavelength, is

-direction). The pattern of oscillations is thus periodic in space. The spatial repetition period, which is generally termed the wavelength, is

. [This follows from Equation (4.12) because

. [This follows from Equation (4.12) because

is a periodic function with period

is a periodic function with period

: i.e.,

: i.e.,

.] The constant

.] The constant  , which determines the wavelength, is usually referred to as the wavenumber. Thus, a

small wavenumber corresponds to a long wavelength, and vice versa.

The type of solution specified in Equation (4.12) is generally

known as a standing wave. It is a wave because it is periodic

in both space and time. (An oscillation is periodic in time only.) It is

a standing wave, rather than a traveling wave, because the points

of maximum and minimum amplitude oscillation are stationary (in

, which determines the wavelength, is usually referred to as the wavenumber. Thus, a

small wavenumber corresponds to a long wavelength, and vice versa.

The type of solution specified in Equation (4.12) is generally

known as a standing wave. It is a wave because it is periodic

in both space and time. (An oscillation is periodic in time only.) It is

a standing wave, rather than a traveling wave, because the points

of maximum and minimum amplitude oscillation are stationary (in  ). See Figure 4.4.

). See Figure 4.4.

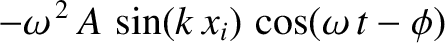

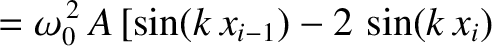

Substituting Equation (4.12) into Equation (4.8), we obtain

|

|

|

![$\displaystyle ~~\left.+\sin(k\,x_{i+1})\right]\,\cos(\omega\,t-\phi),$](img916.png) |

(4.13) |

![$\displaystyle -\omega^{\,2}\,\sin(k\,x_i)=\omega_0^{\,2}\left(\sin[k\,(x_i-a)] -2\,\sin(k\,x_i)

+\sin[k\,(x_i+a)]\right).$](img917.png) |

(4.14) |

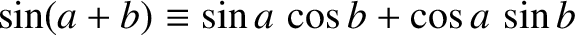

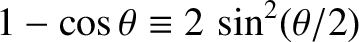

(see Appendix B), we get

(see Appendix B), we get

![$\displaystyle -\omega^{\,2}\,\sin(k\,x_i)=\omega_0^{\,2}\left[\cos(k\,a)-2+\cos(k\,a)\right]\sin(k\,x_i),$](img919.png) |

(4.15) |

. (See Appendix B.) An expression, such as Equation (4.16), that determines the angular frequency,

. (See Appendix B.) An expression, such as Equation (4.16), that determines the angular frequency,  , of

a wave in terms of its wavenumber,

, of

a wave in terms of its wavenumber,  , is generally termed a dispersion relation.

, is generally termed a dispersion relation.

The solution (4.12) is only physical provided

. In other words,

provided the two ends of the string remain stationary. The first constraint

is automatically satisfied, because

. In other words,

provided the two ends of the string remain stationary. The first constraint

is automatically satisfied, because  . See Equation (4.1). The second constraint

implies that

. See Equation (4.1). The second constraint

implies that

![$\displaystyle \sin(k\,x_{N+1}) = \sin[(N+1)\,k\,a] = 0.$](img923.png) |

(4.17) |

is known as a mode number. A small mode number translates to a small wavenumber, and, hence, to a

long wavelength, and vice versa. We conclude that the possible wavenumbers,

is known as a mode number. A small mode number translates to a small wavenumber, and, hence, to a

long wavelength, and vice versa. We conclude that the possible wavenumbers,  , of the normal modes of the system are

quantized such that they are integer multiples of

, of the normal modes of the system are

quantized such that they are integer multiples of

![$\pi/[(N+1)\,a]$](img925.png) .

Thus, the

.

Thus, the  th normal mode is

associated with the characteristic pattern of bead displacements

where

Here, the integer

th normal mode is

associated with the characteristic pattern of bead displacements

where

Here, the integer  indexes the beads, whereas the mode number

indexes the beads, whereas the mode number  indexes the normal modes. Furthermore,

indexes the normal modes. Furthermore,

and

and  are arbitrary constants determined by the initial conditions.

Of course,

are arbitrary constants determined by the initial conditions.

Of course,  is the peak amplitude of the

is the peak amplitude of the  th normal mode, whereas

th normal mode, whereas  is the associated phase angle.

is the associated phase angle.

How many unique normal modes does the system possess? At first sight, it

might seem that there are an infinite number of normal modes, corresponding to the

infinite number of possible values that the integer  can take. However, this is not

the case. For instance, if

can take. However, this is not

the case. For instance, if  or

or  then all of the

then all of the  are zero.

Clearly, these cases are not real normal modes. Moreover, it can be

demonstrated that

are zero.

Clearly, these cases are not real normal modes. Moreover, it can be

demonstrated that

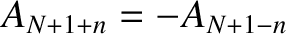

|

|

(4.21) |

|

|

(4.22) |

and

and

, as well as

, as well as

|

|

(4.23) |

|

|

(4.24) |

and

and

. We,

thus, conclude that only those normal modes that have

. We,

thus, conclude that only those normal modes that have  in the

range

in the

range  to

to  correspond to unique modes. Modes with

correspond to unique modes. Modes with  values lying outside

this range are either null modes, or modes that are identical to other modes

with

values lying outside

this range are either null modes, or modes that are identical to other modes

with  values lying within the prescribed range. It follows that

there are

values lying within the prescribed range. It follows that

there are  unique normal modes of the form (4.19). Hence, given that we are dealing with an

unique normal modes of the form (4.19). Hence, given that we are dealing with an  degree of

freedom system, which we would expect to only possess

degree of

freedom system, which we would expect to only possess  unique normal modes, we can be sure that we have found all the normal modes.

unique normal modes, we can be sure that we have found all the normal modes.

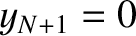

![\includegraphics[width=1\textwidth]{Chapter04/fig4_03.eps}](img946.png) |

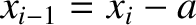

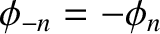

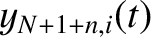

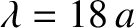

Figure 4.3 illustrates the spatial variation of the normal modes of a beaded string possessing eight

beads. That is, an  system. It can be seen that the low-

system. It can be seen that the low- —that is, long-wavelength—modes cause the string to oscillate in a

fairly smoothly-varying (in

—that is, long-wavelength—modes cause the string to oscillate in a

fairly smoothly-varying (in  ) sine wave pattern. On the other hand, the high-

) sine wave pattern. On the other hand, the high- —that is, short-wavelength—modes cause the string to oscillate in a

rapidly-varying zig-zag pattern that bears little resemblance to a sine wave.

The crucial distinction between the two different types of mode is that the

wavelength of the oscillation (in the

—that is, short-wavelength—modes cause the string to oscillate in a

rapidly-varying zig-zag pattern that bears little resemblance to a sine wave.

The crucial distinction between the two different types of mode is that the

wavelength of the oscillation (in the  -direction) is much larger

than the bead spacing in the former case, while it is similar to

the bead spacing in the latter. For instance,

-direction) is much larger

than the bead spacing in the former case, while it is similar to

the bead spacing in the latter. For instance,

for the

for the  mode,

mode,

for the

for the  mode, but

mode, but

for the

for the  mode.

mode.

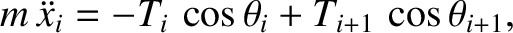

![\includegraphics[width=0.9\textwidth]{Chapter04/fig4_04.eps}](img954.png) |

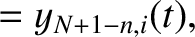

Figure 4.5 displays the temporal variation of the  normal mode of

an

normal mode of

an  beaded string. It can be seen

that the beads oscillate in phase with one another. In other words, they all attain their maximal

transverse displacements, and pass through zero displacement, simultaneously.

Moreover, the mid-way point of the string always remains stationary. Such a point is

known as a node. The

beaded string. It can be seen

that the beads oscillate in phase with one another. In other words, they all attain their maximal

transverse displacements, and pass through zero displacement, simultaneously.

Moreover, the mid-way point of the string always remains stationary. Such a point is

known as a node. The  normal mode has two nodes (counting the

stationary points at each end of the string as nodes), the

normal mode has two nodes (counting the

stationary points at each end of the string as nodes), the  mode has three nodes, the

mode has three nodes, the  mode four nodes, et cetera. In fact, the existence

of nodes is one of the distinguishing features of a standing wave.

mode four nodes, et cetera. In fact, the existence

of nodes is one of the distinguishing features of a standing wave.

Figure 4.5 shows the normal frequencies of an  beaded string plotted as a function of the normalized wavenumber. Recall that, for an

beaded string plotted as a function of the normalized wavenumber. Recall that, for an  system,

the relationship between the normalized wavenumber,

system,

the relationship between the normalized wavenumber,  , and the

mode number,

, and the

mode number,  , is

, is

.

It can be seen that the angular frequency increases as the wavenumber

increases, which implies that shorter wavelength modes have

higher oscillation frequencies. The dependence of the angular frequency

on the normalized wavenumber,

.

It can be seen that the angular frequency increases as the wavenumber

increases, which implies that shorter wavelength modes have

higher oscillation frequencies. The dependence of the angular frequency

on the normalized wavenumber,  , is approximately linear when

, is approximately linear when  . Indeed, it can be seen from Equation (4.20) that if

. Indeed, it can be seen from Equation (4.20) that if  then the small-angle approximation

then the small-angle approximation

yields a linear dispersion relation

of the form

yields a linear dispersion relation

of the form

) have approximately linear dispersion

relations in which their angular frequencies are directly proportional

to their mode numbers. However, it is evident from the figure that this linear relationship

breaks down as

) have approximately linear dispersion

relations in which their angular frequencies are directly proportional

to their mode numbers. However, it is evident from the figure that this linear relationship

breaks down as

, and the mode wavelength consequently becomes

similar to the bead spacing.

, and the mode wavelength consequently becomes

similar to the bead spacing.