Next: Exercises Up: Damped and Driven Harmonic Previous: Driven LCR Circuit Contents

|

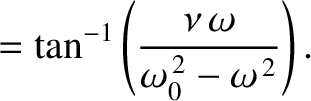

![$\displaystyle = \frac{\omega_0^{\,2}\,\hat{X}}{\left[(\omega_0^{\,2}-\omega^{\,2})^{\,2}+\nu^{\,2}\,\omega^{\,2}\right]^{1/2}},$](img590.png) |

(2.75) |

|

|

(2.76) |

|

(2.77) |

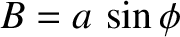

, and

, and  and

and  are arbitrary constants. [In terms of the standard solution, (2.12),

are arbitrary constants. [In terms of the standard solution, (2.12),

and

and

.]

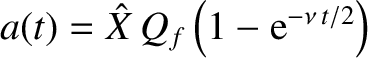

Thus, a more general solution to Equation (2.73) is

In fact, because the preceding solution contains two arbitrary constants, we can be sure

that it is the most general solution. The arbitrary constants,

.]

Thus, a more general solution to Equation (2.73) is

In fact, because the preceding solution contains two arbitrary constants, we can be sure

that it is the most general solution. The arbitrary constants,  and

and  ,

are determined by the initial conditions. Thus, the

most general solution to the driven damped harmonic oscillator equation, (2.73),

consists of two parts: first, the solution (2.74), which oscillates at the driving frequency

,

are determined by the initial conditions. Thus, the

most general solution to the driven damped harmonic oscillator equation, (2.73),

consists of two parts: first, the solution (2.74), which oscillates at the driving frequency  with a constant amplitude, and which is independent of the initial conditions; second, the

solution (2.78), which oscillates at the natural frequency

with a constant amplitude, and which is independent of the initial conditions; second, the

solution (2.78), which oscillates at the natural frequency  with an amplitude that decays exponentially in time, and

which depends on the initial conditions. The former is termed the

time asymptotic solution, because if we wait long enough then it

becomes dominant. The latter is called the transient solution, because if

we wait long enough then it decays away.

with an amplitude that decays exponentially in time, and

which depends on the initial conditions. The former is termed the

time asymptotic solution, because if we wait long enough then it

becomes dominant. The latter is called the transient solution, because if

we wait long enough then it decays away.

![\includegraphics[width=0.8\textwidth]{Chapter02/fig2_07.eps}](img594.png) |

Suppose, for the sake of argument, that the system is initially in its equilibrium

state. In other words,

. It follows from Equation (2.79) that

. It follows from Equation (2.79) that

|

|

(2.80) |

|

|

(2.81) |

), we

can write

), we

can write

|

![$\displaystyle \simeq \frac{\omega_0\,\hat{X}}{[4\,(\omega_0-\omega)^{\,2}+\nu^{\,2}]^{1/2}},$](img607.png) |

(2.84) |

|

![$\displaystyle \simeq \frac{\nu}{[4\,(\omega_0-\omega)^{\,2}+\nu^{\,2}]^{1/2}},$](img608.png) |

(2.85) |

|

![$\displaystyle \simeq \frac{2\,(\omega_0-\omega)}{[4\,(\omega_0-\omega)^{\,2}+\nu^{\,2}]^{1/2}}.$](img609.png) |

(2.86) |

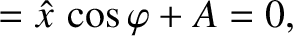

There are a number of interesting cases that are worth discussing. Consider,

first, the situation in which the driving frequency is equal to the resonant frequency; that is,

. In this case, Equation (2.87) reduces to

. In this case, Equation (2.87) reduces to

|

(2.88) |

. Thus, the driven response oscillates at the

resonant frequency,

. Thus, the driven response oscillates at the

resonant frequency,  , because both the time asymptotic and transient solutions

oscillate at this frequency. However, the amplitude of the

oscillation grows monotonically as

, because both the time asymptotic and transient solutions

oscillate at this frequency. However, the amplitude of the

oscillation grows monotonically as

, and

so takes a time of order

, and

so takes a time of order

(i.e., a time of order

(i.e., a time of order  oscillation periods) to attain its final value

oscillation periods) to attain its final value

, which

is, of course, larger that the driving amplitude by the resonant amplification

factor (or quality factor),

, which

is, of course, larger that the driving amplitude by the resonant amplification

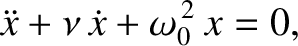

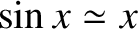

factor (or quality factor),  . This behavior is illustrated in Figure 2.7.

. This behavior is illustrated in Figure 2.7.

![\includegraphics[width=0.8\textwidth]{Chapter02/fig2_08.eps}](img617.png) |

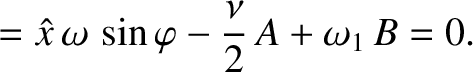

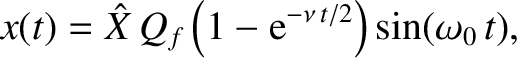

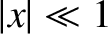

Consider the situation in which there is no damping, so that  . In this

case, Equation (2.87) yields

. In this

case, Equation (2.87) yields

![$\cos a - \cos b \equiv -2\,\sin[(a+b)/2]\,\sin[(a-b)/2]$](img620.png) . (See Appendix B.) It can be seen that the driven response oscillates relatively rapidly at the “sum frequency”

. (See Appendix B.) It can be seen that the driven response oscillates relatively rapidly at the “sum frequency”

with an amplitude

with an amplitude

![$a(t) = \hat{X}\,[\omega_0/(\omega_0-\omega)]\,\sin[(\omega_0-\omega)/t]$](img622.png) that modulates relatively slowly at the

“difference frequency”

that modulates relatively slowly at the

“difference frequency”

. (Recall, that we are assuming that

. (Recall, that we are assuming that

is close to

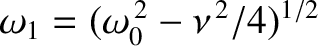

is close to  .) This behavior is illustrated in

Figure 2.8. The amplitude modulations shown

in Figure 2.8 are called beats, and are produced whenever two

sinusoidal oscillations of similar amplitude, and slightly different frequency,

are superposed. In this case, the two oscillations are the time asymptotic solution,

which oscillates at the driving frequency,

.) This behavior is illustrated in

Figure 2.8. The amplitude modulations shown

in Figure 2.8 are called beats, and are produced whenever two

sinusoidal oscillations of similar amplitude, and slightly different frequency,

are superposed. In this case, the two oscillations are the time asymptotic solution,

which oscillates at the driving frequency,  , and the transient

solution, which oscillates at the resonant frequency,

, and the transient

solution, which oscillates at the resonant frequency,  . The beats

modulate at the difference frequency,

. The beats

modulate at the difference frequency,

. In the limit

. In the limit

, Equation (2.89) yields

, Equation (2.89) yields

|

(2.90) |

when

when  . (See Appendix B.) Thus, the resonant response of a

driven undamped oscillator is an oscillation at the resonant frequency whose

amplitude,

. (See Appendix B.) Thus, the resonant response of a

driven undamped oscillator is an oscillation at the resonant frequency whose

amplitude,

, increases linearly in time. In this case, the period of the beats has

effectively become infinite.

, increases linearly in time. In this case, the period of the beats has

effectively become infinite.

Finally, Figure 2.9 illustrates the non-resonant response of a driven damped harmonic oscillator, obtained from Equation (2.87). It can be seen that the driven response grows, showing some initial evidence of beat modulation, but eventually settles down to a steady pattern of oscillation. This behavior occurs because the transient solution, which is needed to produce beats, initially grows, but then damps away, leaving behind the constant amplitude time asymptotic solution.