Next: The Lorentz Force

Up: Magnetism

Previous: Ampère's Experiments

Magnetic fields, like electric fields, are completely

superposable. So, if

a field  is generated by a current

is generated by a current  flowing through some circuit,

and a field

flowing through some circuit,

and a field  is generated by a current

is generated by a current  flowing through another

circuit, then when the currents

flowing through another

circuit, then when the currents  and

and  flow through both circuits

simultaneously the generated magnetic field is

flow through both circuits

simultaneously the generated magnetic field is

.

This is true at all points in space.

.

This is true at all points in space.

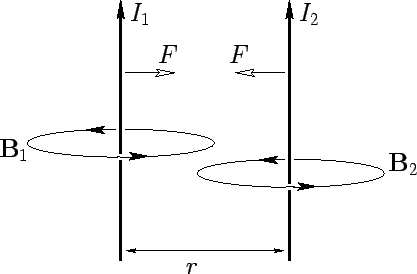

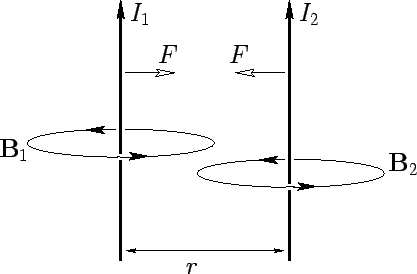

Figure 22:

Two parallel current carrying wires.

|

Consider two parallel wires separated by a perpendicular distance  ,

and carrying electric currents

,

and carrying electric currents  and

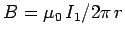

and  , respectively. The magnetic field-strength at the second wire due to the current flowing in the first wire

is

, respectively. The magnetic field-strength at the second wire due to the current flowing in the first wire

is

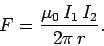

. This field is orientated at right-angles to the second

wire, so the force per unit length exerted on the second wire is

. This field is orientated at right-angles to the second

wire, so the force per unit length exerted on the second wire is

|

(156) |

This follows from Eq. (152), which is valid for continuous wires as well as short

test wires. The force acting on the second wire is directed radially inwards towards

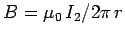

the first wire. The magnetic field-strength at the first wire due to the

current flowing in the second wire is

. This field

is orientated at right-angles to the first wire, so the force per unit length acting

on the first wire is equal and opposite to that acting on the second wire,

according to Eq. (152). Equation (156) is called Ampère's law.

. This field

is orientated at right-angles to the first wire, so the force per unit length acting

on the first wire is equal and opposite to that acting on the second wire,

according to Eq. (152). Equation (156) is called Ampère's law.

Incidentally, Eq. (156) is the basis of the official SI definition of the

ampere, which is:

One ampere is the magnitude of the current which, when flowing in

each of two long parallel wires one meter apart, results in a force

between the wires of exactly

N per meter of length.

N per meter of length.

We can see that it is no accident that the constant  has the

numerical value of exactly

has the

numerical value of exactly

.

The SI system of units is based on four standard units: the meter,

the kilogram, the second, and the ampere. Hence, the SI system is

sometime referred to as the MKSA system. All other units can be derived

from these four standard units. For instance, a coulomb is equivalent to

an ampere-second. You may be wondering why the ampere is the standard

electrical unit, rather than the coulomb, since the latter unit is

clearly more fundamental than the former. The answer is simple. It is very difficult

to measure charge accurately, whereas it is easy to accurately measure electric

current. Clearly, it makes sense to define a standard unit in terms

of something which is easily measurable, rather than something which is

difficult to measure.

.

The SI system of units is based on four standard units: the meter,

the kilogram, the second, and the ampere. Hence, the SI system is

sometime referred to as the MKSA system. All other units can be derived

from these four standard units. For instance, a coulomb is equivalent to

an ampere-second. You may be wondering why the ampere is the standard

electrical unit, rather than the coulomb, since the latter unit is

clearly more fundamental than the former. The answer is simple. It is very difficult

to measure charge accurately, whereas it is easy to accurately measure electric

current. Clearly, it makes sense to define a standard unit in terms

of something which is easily measurable, rather than something which is

difficult to measure.

Next: The Lorentz Force

Up: Magnetism

Previous: Ampère's Experiments

Richard Fitzpatrick

2007-07-14

N per meter of length.