|

A body's mass is a measure of its inertia: i.e., its reluctance to deviate from uniform straight-line motion under the influence of external forces. According to Newton's second law, Eq. (94), if two objects of differing masses are acted upon by forces of the same magnitude then the resulting acceleration of the larger mass is less than that of the smaller mass. In other words, it is more difficult to force the larger mass to deviate from its preferred state of uniform motion in a straight line. Incidentally, the mass of a body is an intrinsic property of that body, and, therefore, does not change if the body is moved to a different place.

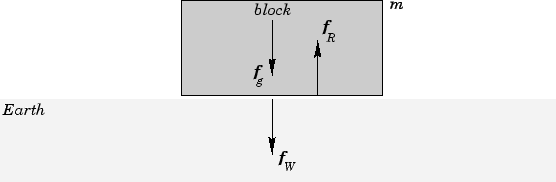

Imagine a block of granite resting on the surface of the Earth.

See Fig. 24. The block experiences

a downward force ![]() due to the gravitational attraction of the Earth. This

force is of magnitude

due to the gravitational attraction of the Earth. This

force is of magnitude ![]() , where

, where ![]() is the mass of the block and

is the mass of the block and ![]() is the acceleration

due to gravity at the surface of the Earth. The block transmits this force to the

ground below it, which is supporting it, and, thereby, preventing it from accelerating

downwards. In other words, the block exerts a downward force

is the acceleration

due to gravity at the surface of the Earth. The block transmits this force to the

ground below it, which is supporting it, and, thereby, preventing it from accelerating

downwards. In other words, the block exerts a downward force ![]() , of magnitude

, of magnitude ![]() ,

on the ground immediately beneath it. We usually refer to this force (or the

magnitude of this force) as the weight of the block. According to Newton's third

law, the ground below the block exerts an upward reaction force

,

on the ground immediately beneath it. We usually refer to this force (or the

magnitude of this force) as the weight of the block. According to Newton's third

law, the ground below the block exerts an upward reaction force ![]() on the block.

This force is also of magnitude

on the block.

This force is also of magnitude ![]() . Thus, the net force acting on the block

is

. Thus, the net force acting on the block

is

![]() , which accounts for the fact that the block

remains stationary.

, which accounts for the fact that the block

remains stationary.

Where, you might ask, is the equal and opposite reaction to the force of gravitational

attraction

![]() exerted by the Earth on the block of granite? It turns out that

this reaction is exerted at the centre of the Earth. In other words, the Earth attracts the

block of granite, and the block of granite attracts the Earth by an equal amount. However,

since the Earth is far more massive than the block, the force

exerted by the granite block at the centre of the Earth has no observable consequence.

exerted by the Earth on the block of granite? It turns out that

this reaction is exerted at the centre of the Earth. In other words, the Earth attracts the

block of granite, and the block of granite attracts the Earth by an equal amount. However,

since the Earth is far more massive than the block, the force

exerted by the granite block at the centre of the Earth has no observable consequence.

So far, we have established that the weight ![]() of a body is the magnitude of the downward

force it exerts on any object which supports it. Thus,

of a body is the magnitude of the downward

force it exerts on any object which supports it. Thus, ![]() , where

, where ![]() is the

mass of the body and

is the

mass of the body and ![]() is the local acceleration due to gravity. Since weight is a force,

it is measured in newtons. A body's weight is location dependent, and is not, therefore,

an intrinsic property of that body. For instance, a body weighing 10N on the surface of

the Earth will only weigh about

is the local acceleration due to gravity. Since weight is a force,

it is measured in newtons. A body's weight is location dependent, and is not, therefore,

an intrinsic property of that body. For instance, a body weighing 10N on the surface of

the Earth will only weigh about ![]() on the surface of Mars, due to the

weaker surface gravity of Mars relative to the Earth.

on the surface of Mars, due to the

weaker surface gravity of Mars relative to the Earth.

Consider a block of mass ![]() resting on the floor of an elevator, as shown in Fig. 25.

Suppose that the elevator is accelerating upwards with acceleration

resting on the floor of an elevator, as shown in Fig. 25.

Suppose that the elevator is accelerating upwards with acceleration ![]() . How does this

acceleration affect the weight of the block?

Of course, the block

experiences a downward force

. How does this

acceleration affect the weight of the block?

Of course, the block

experiences a downward force ![]() due to gravity. Let

due to gravity. Let ![]() be the weight of the block:

by definition, this is the size of the downward force exerted by the block on the

floor of the elevator. From Newton's third law, the floor of the elevator exerts an upward

reaction force of magnitude

be the weight of the block:

by definition, this is the size of the downward force exerted by the block on the

floor of the elevator. From Newton's third law, the floor of the elevator exerts an upward

reaction force of magnitude ![]() on the block. Let us apply Newton's

second law, Eq. (94), to the motion of the block. The mass of the block is

on the block. Let us apply Newton's

second law, Eq. (94), to the motion of the block. The mass of the block is ![]() ,

and its upward acceleration is

,

and its upward acceleration is ![]() . Furthermore, the block is subject to two forces:

a downward force

. Furthermore, the block is subject to two forces:

a downward force ![]() due to gravity, and an upward reaction force

due to gravity, and an upward reaction force ![]() . Hence,

. Hence,

| (95) |

| (96) |

Suppose that the downward acceleration of the elevator matches the acceleration

due to gravity: i.e., ![]() . In this case,

. In this case, ![]() . In other words, the

block becomes weightless! This is the principle behind the so-called

``Vomit Comet'' used by NASA's Johnson Space Centre to train prospective astronauts in

the effects of weightlessness. The ``Vomit Comet'' is actually a KC-135 (a predecessor

of the Boeing 707 which is typically used for refueling military aircraft). The plane

typically ascends to 30,000ft and then accelerates downwards at

. In other words, the

block becomes weightless! This is the principle behind the so-called

``Vomit Comet'' used by NASA's Johnson Space Centre to train prospective astronauts in

the effects of weightlessness. The ``Vomit Comet'' is actually a KC-135 (a predecessor

of the Boeing 707 which is typically used for refueling military aircraft). The plane

typically ascends to 30,000ft and then accelerates downwards at ![]() (i.e.,

drops like a stone) for about 20s, allowing its passengers to feel the effects

of weightlessness during this period. All of the weightless scenes

in the film Apollo 11 were shot in this manner.

(i.e.,

drops like a stone) for about 20s, allowing its passengers to feel the effects

of weightlessness during this period. All of the weightless scenes

in the film Apollo 11 were shot in this manner.

Suppose, finally, that the downward acceleration of the elevator exceeds

the acceleration due to gravity: i.e., ![]() . In this case, the block acquires

a negative weight! What actually happens is that the block flies off the

floor of the elevator and slams into the ceiling: when things have settled down, the

block exerts an upward force (negative weight)

. In this case, the block acquires

a negative weight! What actually happens is that the block flies off the

floor of the elevator and slams into the ceiling: when things have settled down, the

block exerts an upward force (negative weight) ![]() on the ceiling of the elevator.

on the ceiling of the elevator.