Next: Simple Harmonic Oscillator

Up: One-Dimensional Potentials

Previous: Alpha Decay

Consider a particle of mass  and energy

and energy  interacting with the

simple square potential well

interacting with the

simple square potential well

![\begin{displaymath}

V(x) = \left\{\begin{array}{lcl}

-V_0&\mbox{\hspace{1cm}}&\m...

... x\leq a/2$}\ [0.5ex]

0&&\mbox{otherwise}

\end{array}\right.,

\end{displaymath}](img952.png) |

(372) |

where  .

.

Now, if  then the particle is unbounded. Thus, when the particle encounters the well

it is either reflected or transmitted. As is easily demonstrated, the reflection and transmission

probabilities are given by Eqs. (327) and (328), respectively,

where

then the particle is unbounded. Thus, when the particle encounters the well

it is either reflected or transmitted. As is easily demonstrated, the reflection and transmission

probabilities are given by Eqs. (327) and (328), respectively,

where

Suppose, however, that  . In this case, the particle

is bounded (i.e.,

. In this case, the particle

is bounded (i.e.,

as

as

).

Is is possible to find bounded solutions of Schrödinger's equation

in the finite square potential well (372)?

).

Is is possible to find bounded solutions of Schrödinger's equation

in the finite square potential well (372)?

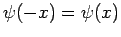

Now, it is easily seen that independent solutions of Schrödinger's equation (301)

in the symmetric [i.e.,  ] potential (372)

must be either totally symmetric [i.e.,

] potential (372)

must be either totally symmetric [i.e.,

], or

totally anti-symmetric [i.e.,

], or

totally anti-symmetric [i.e.,

]. Moreover,

the solutions must satisfy the boundary condition

]. Moreover,

the solutions must satisfy the boundary condition

|

(375) |

Let us, first of all, search for a totally symmetric solution.

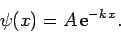

In the region to the left of the well (i.e.  ), the

solution of Schrödinger's equation which satisfies the

boundary condition

), the

solution of Schrödinger's equation which satisfies the

boundary condition

and

and

is

is

|

(376) |

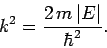

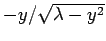

where

|

(377) |

By symmetry, the solution in the region to the right of the well (i.e.,

) is

) is

|

(378) |

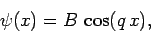

The solution inside the well (i.e.,  ) which

satisfies the symmetry constraint

) which

satisfies the symmetry constraint

is

is

|

(379) |

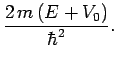

where

|

(380) |

Here, we have assumed that  .

The constraint that

.

The constraint that  and its first derivative be continuous at the

edges of the well (i.e., at

and its first derivative be continuous at the

edges of the well (i.e., at  ) yields

) yields

|

(381) |

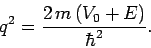

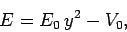

Let  . It follows that

. It follows that

|

(382) |

where

|

(383) |

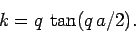

Moreover, Eq. (381) becomes

|

(384) |

with

|

(385) |

Here,  must lie in the range

must lie in the range

: i.e.,

: i.e.,

must lie in the range

must lie in the range  .

.

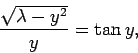

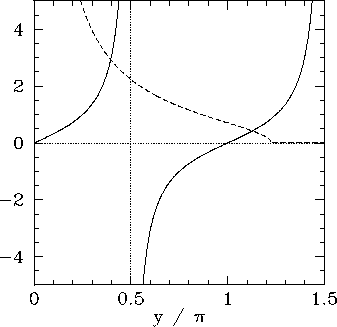

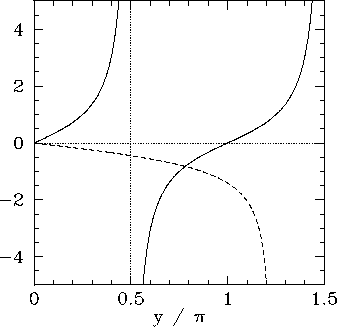

Figure:

The curves  (solid) and

(solid) and

(dashed), calculated for

(dashed), calculated for

. The latter curve takes the

value

. The latter curve takes the

value  when

when

.

.

|

Now, the solutions to Eq. (384) correspond to the

intersection of the curve

with the curve

with the curve

. Figure 16 shows these two curves plotted for

a particular value of

. Figure 16 shows these two curves plotted for

a particular value of  . In this case, the curves intersect

twice, indicating the existence of two totally symmetric bound states in the well.

Moreover, it is evident, from the figure, that as

. In this case, the curves intersect

twice, indicating the existence of two totally symmetric bound states in the well.

Moreover, it is evident, from the figure, that as  increases (i.e., as the well becomes

deeper) there are more and more bound states. However, it is also evident that there is

always at least one totally symmetric bound state, no matter how small

increases (i.e., as the well becomes

deeper) there are more and more bound states. However, it is also evident that there is

always at least one totally symmetric bound state, no matter how small  becomes (i.e., no matter how shallow the well becomes). In the limit

becomes (i.e., no matter how shallow the well becomes). In the limit  (i.e., the limit in which the well becomes very deep), the

solutions to Eq. (384) asymptote to the roots of

(i.e., the limit in which the well becomes very deep), the

solutions to Eq. (384) asymptote to the roots of

.

This gives

.

This gives

, where

, where  is a positive integer, or

is a positive integer, or

|

(386) |

These solutions are equivalent to the odd- infinite square well solutions

specified by Eq. (307).

infinite square well solutions

specified by Eq. (307).

Figure:

The curves  (solid) and

(solid) and

(dashed), calculated for

(dashed), calculated for

.

.

|

For the case of a totally anti-symmetric bound state, similar analysis to the

above yields

|

(387) |

The solutions of this equation correspond to the intersection of the

curve  with the curve

with the curve

. Figure 17 shows these two curves plotted for

the same value of

. Figure 17 shows these two curves plotted for

the same value of  as that used in Fig. 16. In this

case, the curves intersect once, indicating the existence of

a single totally anti-symmetric bound state in the well. It is, again, evident, from the figure, that as

as that used in Fig. 16. In this

case, the curves intersect once, indicating the existence of

a single totally anti-symmetric bound state in the well. It is, again, evident, from the figure, that as  increases (i.e., as the well becomes

deeper) there are more and more bound states. However, it is also evident that

when

increases (i.e., as the well becomes

deeper) there are more and more bound states. However, it is also evident that

when  becomes sufficiently small [i.e.,

becomes sufficiently small [i.e.,

] then there is no totally

anti-symmetric bound state. In other words, a very shallow potential well

always possesses a totally symmetric bound state, but does not generally

possess a totally anti-symmetric bound state. In the limit

] then there is no totally

anti-symmetric bound state. In other words, a very shallow potential well

always possesses a totally symmetric bound state, but does not generally

possess a totally anti-symmetric bound state. In the limit  (i.e., the limit in which the well becomes very deep), the

solutions to Eq. (387) asymptote to the roots of

(i.e., the limit in which the well becomes very deep), the

solutions to Eq. (387) asymptote to the roots of  .

This gives

.

This gives  , where

, where  is a positive integer, or

is a positive integer, or

|

(388) |

These solutions are equivalent to the even- infinite square well solutions

specified by Eq. (307).

infinite square well solutions

specified by Eq. (307).

Next: Simple Harmonic Oscillator

Up: One-Dimensional Potentials

Previous: Alpha Decay

Richard Fitzpatrick

2010-07-20

![\begin{displaymath}

V(x) = \left\{\begin{array}{lcl}

-V_0&\mbox{\hspace{1cm}}&\m...

... x\leq a/2$}\ [0.5ex]

0&&\mbox{otherwise}

\end{array}\right.,

\end{displaymath}](img952.png)

![]() then the particle is unbounded. Thus, when the particle encounters the well

it is either reflected or transmitted. As is easily demonstrated, the reflection and transmission

probabilities are given by Eqs. (327) and (328), respectively,

where

then the particle is unbounded. Thus, when the particle encounters the well

it is either reflected or transmitted. As is easily demonstrated, the reflection and transmission

probabilities are given by Eqs. (327) and (328), respectively,

where

![]() . In this case, the particle

is bounded (i.e.,

. In this case, the particle

is bounded (i.e.,

![]() as

as

![]() ).

Is is possible to find bounded solutions of Schrödinger's equation

in the finite square potential well (372)?

).

Is is possible to find bounded solutions of Schrödinger's equation

in the finite square potential well (372)?

![]() ] potential (372)

must be either totally symmetric [i.e.,

] potential (372)

must be either totally symmetric [i.e.,

![]() ], or

totally anti-symmetric [i.e.,

], or

totally anti-symmetric [i.e.,

![]() ]. Moreover,

the solutions must satisfy the boundary condition

]. Moreover,

the solutions must satisfy the boundary condition

![]() ), the

solution of Schrödinger's equation which satisfies the

boundary condition

), the

solution of Schrödinger's equation which satisfies the

boundary condition

![]() and

and

![]() is

is

![]() . It follows that

. It follows that

![]() with the curve

with the curve

![]() . Figure 16 shows these two curves plotted for

a particular value of

. Figure 16 shows these two curves plotted for

a particular value of ![]() . In this case, the curves intersect

twice, indicating the existence of two totally symmetric bound states in the well.

Moreover, it is evident, from the figure, that as

. In this case, the curves intersect

twice, indicating the existence of two totally symmetric bound states in the well.

Moreover, it is evident, from the figure, that as ![]() increases (i.e., as the well becomes

deeper) there are more and more bound states. However, it is also evident that there is

always at least one totally symmetric bound state, no matter how small

increases (i.e., as the well becomes

deeper) there are more and more bound states. However, it is also evident that there is

always at least one totally symmetric bound state, no matter how small ![]() becomes (i.e., no matter how shallow the well becomes). In the limit

becomes (i.e., no matter how shallow the well becomes). In the limit ![]() (i.e., the limit in which the well becomes very deep), the

solutions to Eq. (384) asymptote to the roots of

(i.e., the limit in which the well becomes very deep), the

solutions to Eq. (384) asymptote to the roots of

![]() .

This gives

.

This gives

![]() , where

, where ![]() is a positive integer, or

is a positive integer, or