Next: Self-inductance

Up: Magnetic induction

Previous: Introduction

We have learned about e.m.f., resistance, and capacitance. Let us now investigate inductance.

Electrical engineers like to reduce all pieces of electrical apparatus to an

equivalent circuit consisting only of e.m.f. sources (e.g., batteries),

inductors, capacitors, and resistors. Clearly, once we understand inductors, we shall

be ready to apply the laws of electromagnetism to electrical circuits.

Consider two stationary loops of wire, labeled 1 and 2. Let us run a steady current

around the first loop to produce a magnetic field

around the first loop to produce a magnetic field  . Some of the field lines

of

. Some of the field lines

of  will pass through the second loop. Let

will pass through the second loop. Let  be the flux

of

be the flux

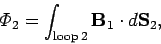

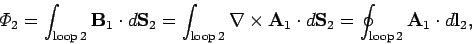

of  through loop 2:

through loop 2:

|

(896) |

where  is a surface element of loop 2.

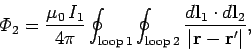

This flux is generally quite difficult to calculate exactly (unless the two loops

have a particularly simple geometry). However, we can infer from the Biot-Savart law,

is a surface element of loop 2.

This flux is generally quite difficult to calculate exactly (unless the two loops

have a particularly simple geometry). However, we can infer from the Biot-Savart law,

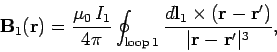

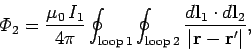

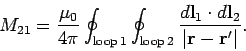

|

(897) |

that the magnitude of  is proportional to the current

is proportional to the current  .

This is

ultimately a consequence of the linearity of Maxwell's equations.

Here,

.

This is

ultimately a consequence of the linearity of Maxwell's equations.

Here,  is a line element of loop 1 located at position

vector

is a line element of loop 1 located at position

vector  .

It follows that

the flux

.

It follows that

the flux  must also be proportional to

must also be proportional to  . Thus, we can write

. Thus, we can write

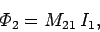

|

(898) |

where  is the constant of proportionality. This constant is called

the mutual inductance of the two loops.

is the constant of proportionality. This constant is called

the mutual inductance of the two loops.

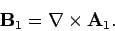

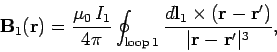

Let us write the magnetic field  in terms of a vector potential

in terms of a vector potential  , so that

, so that

|

(899) |

It follows from Stokes' theorem that

|

(900) |

where  is a line element of loop 2.

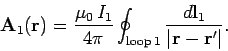

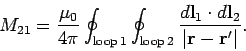

However, we know that

is a line element of loop 2.

However, we know that

|

(901) |

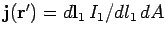

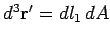

The above equation is just a special case of the more general law,

|

(902) |

for

and

and

, where

, where

is the cross-sectional area of loop 1. Thus,

is the cross-sectional area of loop 1. Thus,

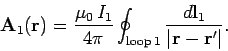

|

(903) |

where  is now the position vector of the line element

is now the position vector of the line element  of loop 2. The above equation implies that

of loop 2. The above equation implies that

|

(904) |

In fact, mutual

inductances are rarely worked out from first principles--it is usually

too difficult. However, the above formula tells us two important things.

Firstly, the mutual inductance of two loops is a purely geometric quantity,

having to do with the sizes, shapes, and relative orientations of the loops.

Secondly, the integral is unchanged if we switch the roles of loops 1 and 2.

In other words,

|

(905) |

In fact, we can drop the subscripts, and just call these quantities  .

This is a rather surprising result. It implies that no matter what the shapes and

relative positions of the two loops, the magnetic flux through loop 2 when we run a

current

.

This is a rather surprising result. It implies that no matter what the shapes and

relative positions of the two loops, the magnetic flux through loop 2 when we run a

current  around loop 1 is exactly the same as the flux through loop 1

when we send the same current around loop 2.

around loop 1 is exactly the same as the flux through loop 1

when we send the same current around loop 2.

We have seen that a current  flowing around some loop, 1, generates a magnetic

flux linking some other loop, 2. However, flux is also generated through the

first loop. As before, the magnetic field, and, therefore, the flux

flowing around some loop, 1, generates a magnetic

flux linking some other loop, 2. However, flux is also generated through the

first loop. As before, the magnetic field, and, therefore, the flux  ,

is proportional to the current, so we can write

,

is proportional to the current, so we can write

|

(906) |

The constant of proportionality  is called the self-inductance. Like

is called the self-inductance. Like

it only depends on the geometry of the loop.

it only depends on the geometry of the loop.

Inductance is measured in S.I. units called henries (H): 1 henry is 1 volt-second

per ampere. The henry, like the farad, is a rather unwieldy unit, since most real-life inductors have a inductances of order a micro-henry.

Next: Self-inductance

Up: Magnetic induction

Previous: Introduction

Richard Fitzpatrick

2006-02-02

![]() around the first loop to produce a magnetic field

around the first loop to produce a magnetic field ![]() . Some of the field lines

of

. Some of the field lines

of ![]() will pass through the second loop. Let

will pass through the second loop. Let ![]() be the flux

of

be the flux

of ![]() through loop 2:

through loop 2:

![]() in terms of a vector potential

in terms of a vector potential ![]() , so that

, so that

![]() flowing around some loop, 1, generates a magnetic

flux linking some other loop, 2. However, flux is also generated through the

first loop. As before, the magnetic field, and, therefore, the flux

flowing around some loop, 1, generates a magnetic

flux linking some other loop, 2. However, flux is also generated through the

first loop. As before, the magnetic field, and, therefore, the flux ![]() ,

is proportional to the current, so we can write

,

is proportional to the current, so we can write