Next: Electric Dipole Transitions

Up: Time-Dependent Perturbation Theory

Previous: Absorption and Stimulated Emission

Spontaneous Emission of Radiation

So far, we have calculated the transition rates

between two atomic states induced by external electromagnetic radiation. This process is known as absorption when the energy of the final state exceeds that

of the initial state, and stimulated emission when the energy of the final state is less than that

of the initial state. Now, in the absence of any external radiation, we would

not expect an atom in a given state to spontaneously jump into a

state with a higher energy. On the other hand, it should be possible for

such an atom to spontaneously jump into an state with a lower energy

via the emission of a photon whose energy is equal to the difference

between the energies of the initial and final states. This process is known as spontaneous emission.

We can derive the rate of spontaneous emission between two atomic states

from a knowledge of the corresponding absorption and stimulated

emission rates using a famous thermodynamic argument initially formulated by Einstein [38].

Consider a very large ensemble of similar atoms placed inside a closed cavity whose walls (which are assumed to be perfect emitters and absorbers of radiation) are held at

the constant temperature  . Let the system have attained thermal equilibrium.

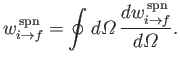

According to statistical thermodynamics, the cavity is filled with so-called black-body electromagnetic

radiation whose energy spectrum is [91]

. Let the system have attained thermal equilibrium.

According to statistical thermodynamics, the cavity is filled with so-called black-body electromagnetic

radiation whose energy spectrum is [91]

|

(8.153) |

where  is the Boltzmann constant. This well-known result was first

obtained by Max Planck in 1900 [82,83].

is the Boltzmann constant. This well-known result was first

obtained by Max Planck in 1900 [82,83].

Consider two atomic states, labeled  and

and  , with

, with  . One

of the tenants of statistical thermodynamics is that in thermal equilibrium

we have so-called detailed balance. (See Section 8.8.) This means that, irrespective

of any other atomic states, the rate at which atoms in the ensemble leave

state

. One

of the tenants of statistical thermodynamics is that in thermal equilibrium

we have so-called detailed balance. (See Section 8.8.) This means that, irrespective

of any other atomic states, the rate at which atoms in the ensemble leave

state  due to transitions to state

due to transitions to state  is exactly balanced by the

rate at which atoms enter state

is exactly balanced by the

rate at which atoms enter state  due to transitions from state

due to transitions from state  .

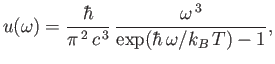

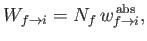

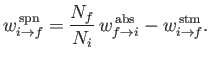

The former rate (i.e., number of transitions per unit time in the ensemble) is written

.

The former rate (i.e., number of transitions per unit time in the ensemble) is written

|

(8.154) |

where

and

and

are the rates of spontaneous and stimulated emission,

respectively,

(for a single atom) between

states

are the rates of spontaneous and stimulated emission,

respectively,

(for a single atom) between

states  and

and  , and

, and  is the number of atoms in the ensemble

in state

is the number of atoms in the ensemble

in state  . Likewise, the latter rate takes the form

. Likewise, the latter rate takes the form

|

(8.155) |

where

is the rate of absorption (for a single atom) between states

is the rate of absorption (for a single atom) between states  and

and  , and

, and  is the number of atoms in the ensemble in state

is the number of atoms in the ensemble in state  .

The previous expressions describe how atoms in the ensemble make transitions from

state

.

The previous expressions describe how atoms in the ensemble make transitions from

state  to state

to state  via a combination of spontaneous and stimulated emission, and make the reverse transition as a consequence of absorption.

In thermal equilibrium, we have

via a combination of spontaneous and stimulated emission, and make the reverse transition as a consequence of absorption.

In thermal equilibrium, we have

,

which gives

,

which gives

|

(8.156) |

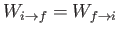

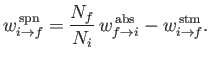

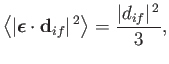

Equations (8.149) and (8.150) imply that

|

(8.157) |

where

, and the large angle brackets denote an average over all possible polarization directions of the incident radiation (because, in equilibrium, the

radiation inside the cavity is isotropic).

In fact, it is easily demonstrated that

, and the large angle brackets denote an average over all possible polarization directions of the incident radiation (because, in equilibrium, the

radiation inside the cavity is isotropic).

In fact, it is easily demonstrated that

|

(8.158) |

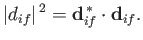

where

|

(8.159) |

(See Exercise 7.)

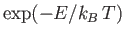

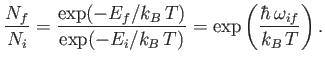

Now, another famous result in statistical thermodynamics is that,

in thermal equilibrium, the number of atoms in an ensemble occupying

a state of energy  is proportional to

is proportional to

[91]. This implies

that

[91]. This implies

that

|

(8.160) |

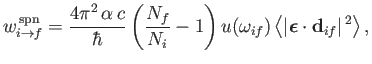

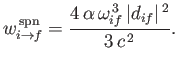

Thus, it follows from Equations (8.156), (8.160), (8.161), and (8.163) that the rate of spontaneous emission between states

and

and  takes the form

takes the form

|

(8.161) |

Note, that, although the previous result has been derived for

an atom in a radiation-filled cavity, it remains correct even in the absence

of radiation.

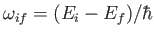

The direction of propagation of a photon spontaneously emitted by an atom is specified by its normalized wavevector,  .

Likewise, the electric polarization direction of the photon is specified by the unit vector

.

Likewise, the electric polarization direction of the photon is specified by the unit vector

.

However,

.

However,

, which implies that

, which implies that

,

where

,

where

. Here, the unit vectors

. Here, the unit vectors

,

,

, and

, and  are

mutually perpendicular, and form a right-handed set (i.e.,

are

mutually perpendicular, and form a right-handed set (i.e.,

).

The vectors

).

The vectors

and

and

represent the two possible independent electric polarization directions of

the emitted photon. Equation (8.164) generalizes to give [77]

represent the two possible independent electric polarization directions of

the emitted photon. Equation (8.164) generalizes to give [77]

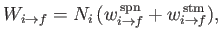

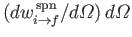

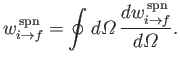

where

is the rate of spontaneous

emission of photons whose propagation directions lie in the range of solid angle

is the rate of spontaneous

emission of photons whose propagation directions lie in the range of solid angle

.

Of course,

.

Of course,

|

(8.163) |

(See Exercise 8.)

Next: Electric Dipole Transitions

Up: Time-Dependent Perturbation Theory

Previous: Absorption and Stimulated Emission

Richard Fitzpatrick

2016-01-22

![]() . Let the system have attained thermal equilibrium.

According to statistical thermodynamics, the cavity is filled with so-called black-body electromagnetic

radiation whose energy spectrum is [91]

. Let the system have attained thermal equilibrium.

According to statistical thermodynamics, the cavity is filled with so-called black-body electromagnetic

radiation whose energy spectrum is [91]

![]() and

and ![]() , with

, with ![]() . One

of the tenants of statistical thermodynamics is that in thermal equilibrium

we have so-called detailed balance. (See Section 8.8.) This means that, irrespective

of any other atomic states, the rate at which atoms in the ensemble leave

state

. One

of the tenants of statistical thermodynamics is that in thermal equilibrium

we have so-called detailed balance. (See Section 8.8.) This means that, irrespective

of any other atomic states, the rate at which atoms in the ensemble leave

state ![]() due to transitions to state

due to transitions to state ![]() is exactly balanced by the

rate at which atoms enter state

is exactly balanced by the

rate at which atoms enter state ![]() due to transitions from state

due to transitions from state ![]() .

The former rate (i.e., number of transitions per unit time in the ensemble) is written

.

The former rate (i.e., number of transitions per unit time in the ensemble) is written

![]() .

Likewise, the electric polarization direction of the photon is specified by the unit vector

.

Likewise, the electric polarization direction of the photon is specified by the unit vector

![]() .

However,

.

However,

![]()

![]() , which implies that

, which implies that

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() ,

where

,

where

![]() . Here, the unit vectors

. Here, the unit vectors

![]()

![]() ,

,

![]()

![]() , and

, and ![]() are

mutually perpendicular, and form a right-handed set (i.e.,

are

mutually perpendicular, and form a right-handed set (i.e.,

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() ).

The vectors

).

The vectors

![]()

![]() and

and

![]()

![]() represent the two possible independent electric polarization directions of

the emitted photon. Equation (8.164) generalizes to give [77]

represent the two possible independent electric polarization directions of

the emitted photon. Equation (8.164) generalizes to give [77]