Next: Kepler's Third Law

Up: Planetary Motion

Previous: Kepler's Second Law

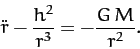

Our planet's radial equation of motion, (228), can be combined with

Equation (247) to give

|

(250) |

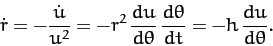

Suppose that  . It follows that

. It follows that

|

(251) |

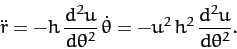

Likewise,

|

(252) |

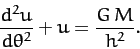

Hence, Equation (250) can be written in the linear form

|

(253) |

The general solution to the above equation is

![\begin{displaymath}

u(\theta) = \frac{G\,M}{h^2}\left[1 - e\,\cos(\theta-\theta_0)\right],

\end{displaymath}](img748.png) |

(254) |

where  and

and  are arbitrary constants. Without loss of generality, we can

set

are arbitrary constants. Without loss of generality, we can

set  by rotating our coordinate system about the

by rotating our coordinate system about the  -axis. Thus,

we obtain

-axis. Thus,

we obtain

|

(255) |

where

|

(256) |

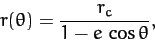

We immediately recognize Equation (255) as the equation of a conic

section which is confocal with the origin (i.e., with the Sun).

Specifically, for  , Equation (255) is the equation of an ellipse

which is confocal with the Sun. Thus, the orbit of our planet

around the Sun in a confocal ellipse--this is Kepler's first law

of planetary motion. Of course, a planet cannot have a parabolic

or a hyperbolic orbit, since such orbits are only appropriate to objects which are ultimately able to escape from the Sun's gravitational field.

, Equation (255) is the equation of an ellipse

which is confocal with the Sun. Thus, the orbit of our planet

around the Sun in a confocal ellipse--this is Kepler's first law

of planetary motion. Of course, a planet cannot have a parabolic

or a hyperbolic orbit, since such orbits are only appropriate to objects which are ultimately able to escape from the Sun's gravitational field.

Next: Kepler's Third Law

Up: Planetary Motion

Previous: Kepler's Second Law

Richard Fitzpatrick

2011-03-31