Next: Worked Examples

Up: Electric Current

Previous: Energy in DC Circuits

Power and Internal Resistance

Consider a simple circuit in which a battery of emf  and internal

resistance

and internal

resistance  drives a current

drives a current  through an external resistor of resistance

through an external resistor of resistance  (see Fig. 17). The external resistor is usually referred

to as the load resistor. It could stand for either an electric light,

an electric heating element, or, maybe, an electric motor. The

basic purpose of

the circuit is to transfer energy from the battery to the load, where it actually

does something useful for us (e.g., lighting

a light bulb, or lifting a weight). Let us see to what extent the internal resistance

of the battery interferes with this process.

(see Fig. 17). The external resistor is usually referred

to as the load resistor. It could stand for either an electric light,

an electric heating element, or, maybe, an electric motor. The

basic purpose of

the circuit is to transfer energy from the battery to the load, where it actually

does something useful for us (e.g., lighting

a light bulb, or lifting a weight). Let us see to what extent the internal resistance

of the battery interferes with this process.

The equivalent resistance of the circuit is  (since the load resistance is

in series with the internal resistance), so the current flowing in the

circuit is given by

(since the load resistance is

in series with the internal resistance), so the current flowing in the

circuit is given by

|

(145) |

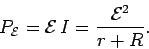

The power output of the emf is simply

|

(146) |

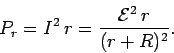

The power dissipated as heat by the internal resistance of the battery is

|

(147) |

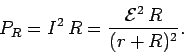

Likewise, the power transferred to the load is

|

(148) |

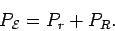

Note that

|

(149) |

Thus, some of the power output of the battery is immediately lost as heat dissipated by the

internal resistance of the battery. The remainder is transmitted to the load.

Let

and

and  . It follows from

Eq. (148) that

. It follows from

Eq. (148) that

|

(150) |

The function  increases monotonically from zero for

increasing

increases monotonically from zero for

increasing  in the range

in the range  , attains

a maximum value of

, attains

a maximum value of  at

at  , and then decreases monotonically with increasing

, and then decreases monotonically with increasing

in the range

in the range  . In other words, if the load resistance

. In other words, if the load resistance  is varied at

constant

is varied at

constant  and

and  then the transferred power attains a maximum

value of

then the transferred power attains a maximum

value of

|

(151) |

when  . This is a very important result in electrical engineering.

Power transfer between a voltage source and an external load is at its most efficient when the

resistance of the load matches the internal resistance of the voltage source.

If the load resistance is too low then most of the power output of the voltage

source is dissipated as heat inside the source itself. If the load resistance

is too high then the current which flows in the circuit is too low to

transfer energy to the load at an appreciable rate. Note that in the optimum case,

. This is a very important result in electrical engineering.

Power transfer between a voltage source and an external load is at its most efficient when the

resistance of the load matches the internal resistance of the voltage source.

If the load resistance is too low then most of the power output of the voltage

source is dissipated as heat inside the source itself. If the load resistance

is too high then the current which flows in the circuit is too low to

transfer energy to the load at an appreciable rate. Note that in the optimum case,

, only half of the power output of the voltage source

is transmitted to the load. The other half is dissipated as heat inside

the source.

Incidentally, electrical engineers call the process by which the resistance of

a load is matched to that of the power supply impedance matching

(impedance is just a fancy name for resistance).

, only half of the power output of the voltage source

is transmitted to the load. The other half is dissipated as heat inside

the source.

Incidentally, electrical engineers call the process by which the resistance of

a load is matched to that of the power supply impedance matching

(impedance is just a fancy name for resistance).

Next: Worked Examples

Up: Electric Current

Previous: Energy in DC Circuits

Richard Fitzpatrick

2007-07-14

![]() (since the load resistance is

in series with the internal resistance), so the current flowing in the

circuit is given by

(since the load resistance is

in series with the internal resistance), so the current flowing in the

circuit is given by

![]() and

and ![]() . It follows from

Eq. (148) that

. It follows from

Eq. (148) that